Foreword | Historical Narratives | Resources | Links | Contact

LAKE ERIE LOST

&

DEFEAT AT MORAVIANTOWN

History is a pattern of timeless moments.

|

|

Lake Erie |

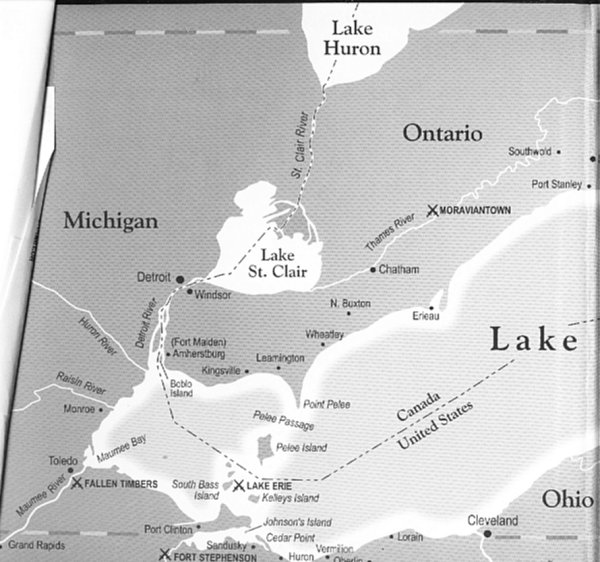

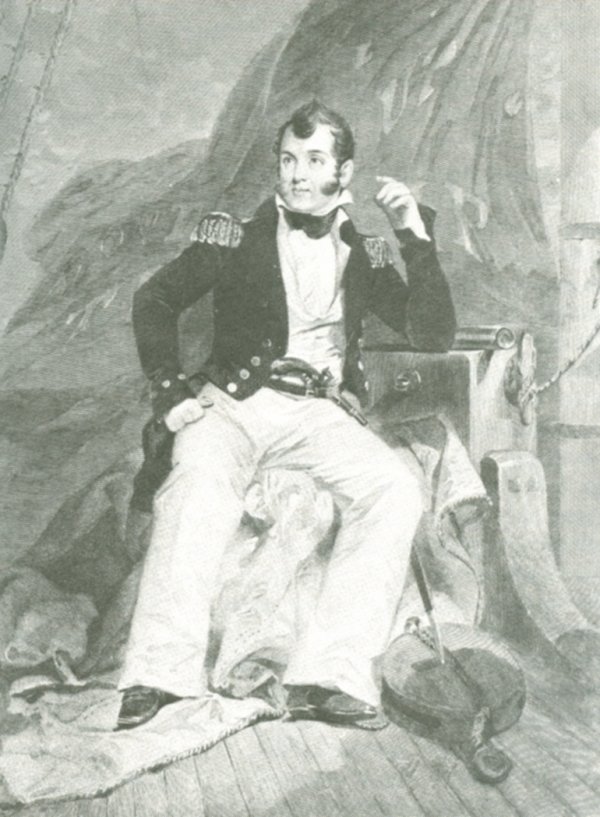

The Americans realized that the key to success in this region lay in wresting control of Lake Erie from the British. A ship-building programme was begun at Presqu'ile (present-day Erie, Pennsylvania) under the direction of Commodore Oliver Hazard Perry, who arrived there in March of 1813. He found unfinished ships and the shipwrights on strike. Appealling to their patriotism, and offering better pay, Perry was able to convince the men to return to work and his fleet was floating in record time by the second week in July, 1813. .

|

|

Oliver Hazard Perry [*] |

Perry was able to launch and fit the following ships: two 480-ton brigs: the Niagara and the Lawrence, which Perry chose as his flagship. The other new vessels were: schooners Ariel, Scorpion and Porcupine. These five new vessels and the fleet of four brought from Black Rock had to be warped up the swift waters of the Niagara River.This process involved hauling a ship along using a cable attached to a fixed object like a capstan. This was generally done in confined waters or when there was no wind. Once in Lake Erie, the American vessels took advantage of thick weather and by clinging to the shallows, they arrived at safe harbour at Presque Isle despite the British precarious hold on Lake Erie and its fleet's strict vigilance.

|

|

Robert Hariot Barclay [**]. |

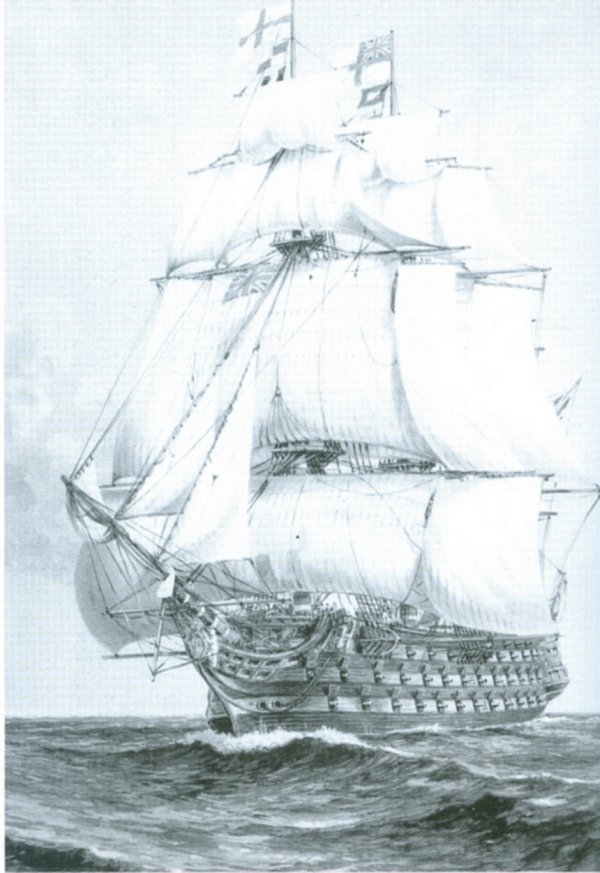

Captain Robert Heriot Barclay was appointed to the command of the British flotilla on Lake Erie in May, 1813, where he was transferred to command when his superior, Sir James Yeo, decided to take the Lake Ontario squadron for himself. The 28-year old Barclay, a proud, alert individual, had served his sovereign for half his life and bore the scars to prove it. Barclay sailed aboard Nelson's great ship Victoria and while serving with Admiral Nelson at Trafalgar, a cannon ball had bounced off his shoulder, severing his his left arm just below the shoulder.

|

|

Victory |

This appointment had been declined by Captain Mulcastor because he found the fleet wanting in almost every respect. With a lieutenant and 19 rejected seaman from the Ontario squadron,

The British fleet consisted of: the Queen Charlotte (16 guns-280 tons) Lady Prevost (12 guns-120 tons) General Hunter (10 guns-74 tons) Erie (3 guns-55 tons) Little Belt (3 guns-54 tons) and Chippewa (1 gun-32 tons). All these vessels had been constructed to carry cargoes. Only one was built for battle - the Detroit, pierced with 18 guns and measured 305 tons. It was under construction at Detroit. To arm it, Fort Amherstburg was stripped bare of 19 guns of four different calibres. Twelve months after the start of the war, this 920-ton fleet [***] comprised the Lake Erie squadron, manned by 108 Canadians and 160 soldiers with not a seaman among them.

Americans had immediate access to the industry of Pittsburg, where Perry personally went to buy anchors, hoops, bolts and other hardware. Requests for supplies reached Washington in five days. The same order from England took five months. Upper Canada produced almost nothing for its own defence. Canvas, rope, guns, shot, cables, anchors, binnacle, bowsprit - all had to be shipped from a British dockyard. Anchors were worth their weight in silver. Every round of shot cost a schilling a pound to transport from Quebec to Lake Erie, ten times more than it cost in England.

Everything from bullets to boots was hauled from Great Britain to Amherstburg along a precarious supply line. It included crossing an ocean, a lake and travelling 300 kilometres up the river and rapids. Sixty kilometres of this distance were shared with the United States, thereby exposing boats and their burthen to shot and shell of the enemy. Frozen for six months of the year, the waterway was open to American attack for the rest of the year.

While Presque Isle's harbour was well sheltered, it presented a special problem for the larger vessels. Brigs drawing at least three metres of water encountered obstacles, since the sandbar across the entrance was less than two metres. The self-same sandbar that protected the vessels as they were being built, impeded their entry into the lake. In order to surmount the sandbar, they had to be stripped of their guns and lifted on floats. To complicate matters further, Barclay's boats, "passed and re-passed the mouth of the harbour," maintaining a tight blockade which lasted until the end of July.

For reasons that have never been satisfactorily explained, Barclay relaxed his blockade and on the 29th, his fleet sank like the sun beyond the horizon, his destination, Long Point. One version of the reason for his unexpected departure was that love loosened the lines of the blockade. "His preoccupation was with a pretty widow," who waited to welcome him at Long Point. Whether true love lured him away or not was never proven. Another reason for raising anchors was to accept an invitation to a party given in his honour. In any case, Barclay must have believed his short sojourn elsewhere would be insufficient time for the Americans slip out and set sail.

Perry never tarried and as soon as Barclay disappeared over the horizon, he sprang into action. After the brigs had been lightened by unloading all stores, guns and ammunition, they were lifted using 'camels', a device developed by the Dutch. Floats filled with water were attached to the sides of the vessel and as the water was pumped out, the camels rose and lifted the vessels. Smaller ships were lightened and simply sailed over the sandbar. Following three days of hectic hastening, Perry sallied forth into the lake to find and fight the British vessels that had so vexed him. His orders were short and sharp: take control of Lake Erie. Then he was told to transport an army led by Brigadier General William Henry Harrison from its camps at Sandusky, Ohio to southwestern Upper Canada.

|

|

Oliver Hazard Perry & Robert H. Barclay |

In a series of fruitless appeals to Commodore Yeo, Barclay's request for "a reinforcement of good Seamen," went unanswered.His only hope of counteracting the rapid growth of the American squadrons,"was tried officers and trusty men from the Navy." Yeo failed to fulfill Barclay's request because the badly needed ordnance and naval stores had been captured or destroyed by the Yanks when York was captured in April 1813. York's seizure contributed mightily to the outcome of the Battle of Lake Erie.

Barclay's main task was to keep the supply line open between Amherstburg and Long Point, the depot at the end of the lake. The necessary supplies simply could not be transported overland satisfactorily using the rutted roads winding through the woods. Only the great rivers and lakes were effective highways. While Barclay's fleet was slightly superior to Perry's in vessels, the lack of naval stores and properly trained seamen placed Barclay at a distinct disadvantage. His reluctance to face the American squadron permitted Perry to dominate the lake and block the shipment by water of badly needed provisions to Amherstburg from Niagara.

Brigadier General Procter, who had been left in command by Brock following Hull's craven capitulation of Detroit.

|

|

Hull hands his sword to Brock |

Procter was charged with holding the southwestern peninsula and maintaining the gains made across the Detroit River by Brock's small force of British regulars and Tecumseh's warriors. With the regular shipment of supplies cut off, Procter found himself in a critical situation. Almost surrounded by hostile shores, his regulars, their Aboriginal allies as well as the civilian population had, "not a day's flour in store." Without food and other vital supplies, Procter's anger and frustration focussed on Barclay, whom Procter believed found too many excuses for failing to confront the enemy. A brigadier-general was a powerful critic for a mere naval captain.

Following some persuasive prompting from Procter, Barclay, although "deplorably manned," with neither guns nor seamen from Yeo at York, Barclay knew he had to face and fight Perry. He pressed into service as sailors a detachment of the 41st regiment, whose infantrymen comprised sixty per cent of his crews. Barclay believed his only hope lay with the 240-ton vessel Detroit still on the stocks in Amherstburg. Even though the ship was rough and unfinished, she was launched and fitted with masts, rigging and canons from the fort.

|

|

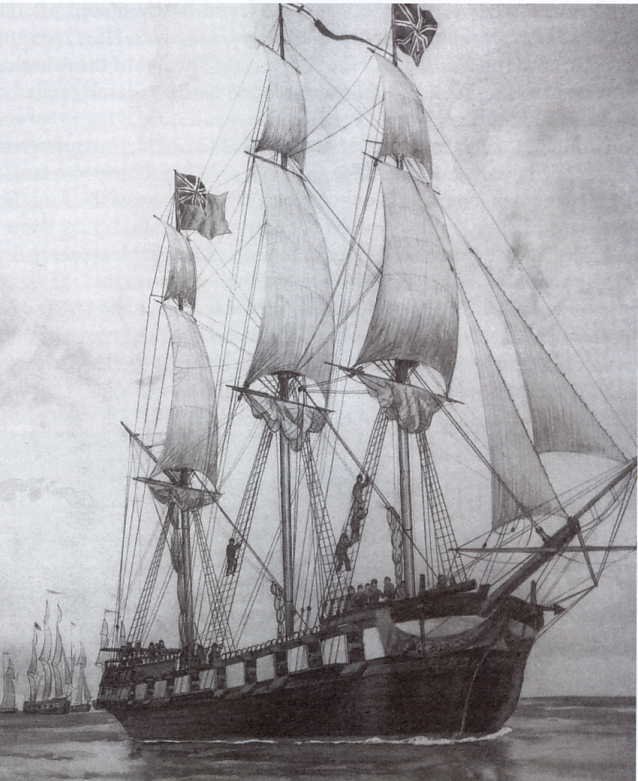

Barclay's Flagship, Detroit |

Matches were lacking to discharge the guns. so Barclay devised a scheme for firing the guns by flashing pistols at the touchholes and this proved to be effective. All ships' decks were covered with sand to prevent them from becoming slippery when blood began to flow. Armed with a curious assortment of guns of every calibre taken from the ramparts of Fort Malden including two American 24-pounders that had been captured by Procter, Barclay prepared his untried and untrained crew to do battle.

|

|

Flashing pistols to touchholes |

On the evening of the 9th of September, 1813, Barclay sallied forth in a favourable wind to face a well-provided force almost doubly superior in fire power. At daybreak on September 10th, his fleet sighted the enemy leeward. As the British commander neared Perry, the wind instantly changed and brought Perry's ship to-windward. This increased the distance between the two and allowed the Americans to use their heavy, long guns with full effect once fighting began, while shells from Briish carronades would plop harmlessly in the water.

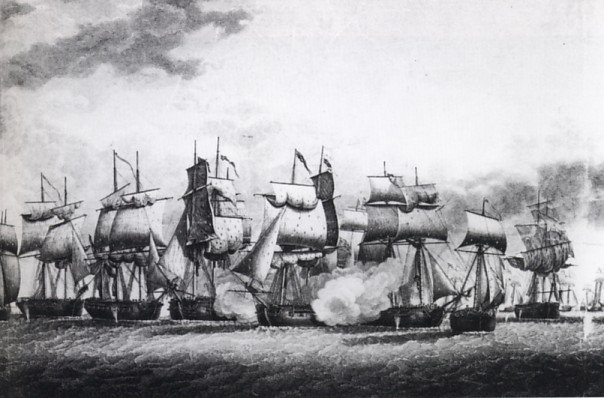

By eleven o'clock both commanders had their fleets drawn up in battle line, but impatient crews had to wait for Neptune to let loose the winds that would permit them to commence the killing.. Under a clear sky and a gentle wind, the fleets met near South Bass Island in the western reaches of the lake.

Barclay's fleet, whose vessels had been freshly caulked and painted red, was a fine sight to behold against the blue lake and cloudless azure sky. All battle flags were flying, polished brass was glittering and acres of new white sail were spotless in the bright September sun. With all sails set the six ships moved in formation. The one-gun schooner Chippewa was in the van, followed by: the Detroit, 10-gun brig General Hunter, the 17-gun Queen Charlotte, the 13-gun schooner Lady Prevost and the sloop Little Belt carrying three guns.

Perry saw Barclay approaching at under three miles an hour before a light, south-westerly wind scarcely ruffling the lake's glassy surface. Perry unfurled his standard, a nine-foot square of blue cloth on which white letters a foot high proclaimed:Don't Give Up The Ship. A bugle sounded from the Detroit and at the same time, the British band struck up Rule Britannia, a patriotic piece declaring, "Britannia ruled the waves." A great cheer rose from her crews.

|

|

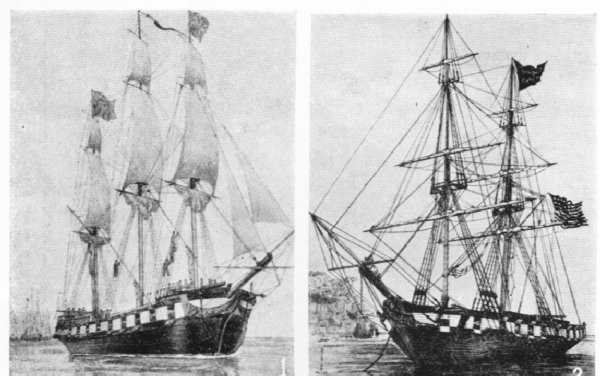

Barclay's Flagship Detroit & Perry's Flagship Niagara |

Perry's fleet included the 20-gun Lawrence, the 20-gun Niagara, the 3-gun brig, Caledonia, and the schooners Ariel, Scorpion, Somers, Porcupine and Tigress, each carrying 10 guns and the sloop Trippe with one gun. Perry's plan was to sail his own ship Lawrence against Barclay in Detroit, the most powerful ship on the lake and Hunter and tiny Chippewa. Another American officer on the Niagara would take on Barclay's second ship, Queen Charlotte, while the American vessels Somers, Porcupine, Tigress and Trippe fought Lady Prevost and Little Belt.

|

|

Barclay's Flagship Detroit |

Perry's nine vessels mounted 15 long guns and 39 32-pound carronades. Barclay's squadron comprised six vessels mounting 35 long guns and 15 24-pound carronades, their smaller calibre meant they were outgunned by the weight of cannon ball metal in Perry's broadsides. The American threw a broadside at close range of about 900 pounds of metal; the British 460 pounds. At long range the Americans threw 280 pounds of metal, the British 195 pounds.

|

|

|

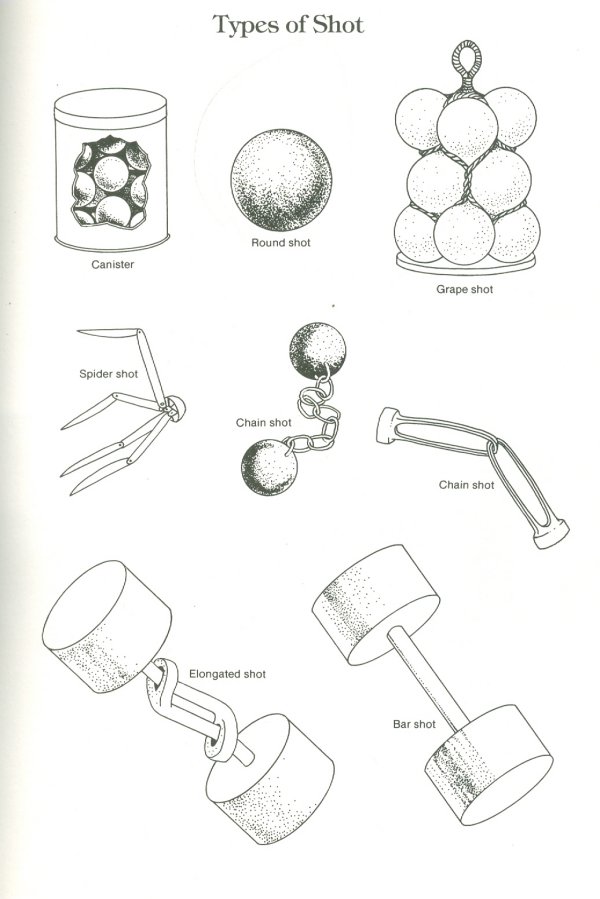

Ammunition consisted of conventional solid iron round-shot, grape, canister, bar-shot, spider shot, chain shot, elongated shot and chain-shot, the latter two linked projectiles that ripped canvas, rigging and spars. Use of red-hot shot to create fires was common, the larger warships carrying small furnaces in which round-shot could be heated. A wet wad was rammed home on top of the powder charge and the glowing ball then inserted with tongs. The iron monsters lept to life when the gun captain put the match to the powder in the touchhole. With a blast and a jet of flame, the cannon pitched forward and then rolled backward in recoil. Anyone slow in stepping aside suffered two broken legs. The loud concussion set off shockwaves that struck the ears like a blow, deafening any gunner who neglected to tie a handkerchief around his head.

Perry had taken on board a hundred sharpshooters, whose task it was to shoot the enemy when the ships closed for battle. These 'marines' manned the ship's fighting tops, tiny platforms high up in the masts used as sniper posts. As the ships drew within musket range, the sharpshooters picked off people on the enemy's decks. Their favourite targets were officers and the sailing master. Their marksmanship was excellent, they picked off most of the officers and thus helped turn this battle from defeat into victory.

All vessels carried their guns in broadside and accurate firepower depended on the skill and experience of the commander in handling his ship, so as to train his rigid battery on the moving target. A sailing vessel with the wind pushing her from the stern was running "before the wind." Forward motion against the wind could be attained only by zig-zagging with the sails trimmed on a slant to catch the wind, a practice called "beating to windward."

Combat usually commenced by preliminary jockeying for the "weather gage," each ship trying to put herself between the wind and her adversary. The weather gage gave the holder the choice of either closing for battle or avoiding combat. It also provided the opportunity to cross the opponent's path and rake her, that is, sweep her with fire from stem to stern while the enemy's cannons could not be brought to bear.

Once the ships collided, other marines stationed on deck threw sharp-pointed anchors called grapnels across the enemy's deck rails to bind the vessels together. Then marines and sailors swarmed over the rails and it was every man for himself, the battle, a deadly free-for-all with pistols, swords, tomahawks and short spears called boarding pikes. A ship surrendered when its commander 'struck,' his colours, that is, ordered the flag to be hauled down.

Both fleets moved slowly in the light air holding their fire. Shortly before noon the leading British ship began to fire. In Barclay's report of the conflict, he stated he commenced action at a quarter before twelve. While some aimed fire at spars, sails and rigging hoping to immobilize enemy ships, the English concentrated their fire on the hull seeking to demolish armaments and kill crew. The Lawrence was the Detroit's target and it took her apart cannon by carronade, spar by sail, brace by bowline, the thunderous broadsides blazing away at point blank range. Her hull became a sieve. Below in the claustrophobic gundecks, shouts, cries and screams accompanied the concussion of cannon, the crash of broken wood and the whiz of lethal splinters. Perry had placed some Kentucky riflemen in his rigging and they sniped so effectively, that all the chief British officers were killed or wounded in the first hour of fighting.

"Victory, seemingly savouring the carnage, stood aloof unwilling to declare for either side." The battle raged with fury - splinters flying, yards falling, masts tumbling, men dropping in every direction, cheers drowning out the agonizing cries of the dying and wounded. At two o'clock, the British ceased firing, expecting the battered Lawrence's flag to be lowered. Perry was determined that he would not make that decision.

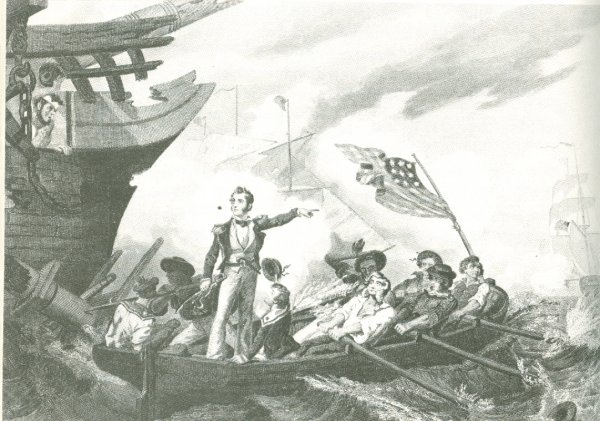

So he took advantage of the blanket of thick gunsmoke and leaped into a rowboat with the, "Don't Give Up The Ship" banner draped over his shoulders .As he lept from the Lawrence, he told the lieutenant remaining in charge that he was delegated to decide whether to fight on or lower the flag. Perry was rowed to the Niagara, which had remained out of range of the Queen Charlotte's carronades and sustained little damage. Barclay saw this and wrote later that he observed, "a rowboat passing with Perry in it to the Niagara." Shortly thereafter, the Lawrence struck her colours. The Detroit ceased firing, but having only one boat and that cut to pieces, she could not take possession. |

|

Perry Parting from the Lawrence |

Perry's personal flag was raised over the Niagara and as soon as it advanced towards the Detroit, the Lawrence, which had drifted out of reach of the Detroit's guns, re-hoisted her colours, a no-no for all nautical types and an act considered a shameful proceeding. Perry later in his subsequent report of the action glossed over this. "It was unspeakable pain that I saw, soon after I got on board the Niagara, the flag of Lawrence come down, although I was perfectly sensible that she had been defended to the last and that to have continued to make a shew of resistance would have been a wanton sacrifice of her brave crew. But the enemy was not able to take possession of her and circumstances soon permitted her flag again to be hoisted."[**]

Niagara's batteries battered the British vessels. The Detroit, Queen Charlotte and Lawrence suffered greatly in hulls, masts and rigging. The American ships kept their distance, so Barclay's carronades were useless. "Our losses were severe," wrote Barclay. "Every officer commanding vessels and their seconds were either killed or wounded so severely as to be unable to keep the deck." Barclay was struck by an iron ball that shatterd the shoulder blade of his surviving arm. With blood gushing from the open wound, he collapsed and was carried below to the surgeon . British losses killed and wounded numbered 135. Perry was uninjured and lost two officers: a lieutenant and a midshipman. His casualties totalled 123.

An officer aboard Detroit raised a white handkerchief on a pike to signal the ship's surrender. Queen Charlotte, General Hunter, and Lady Prevost all struck their colours. Chippawa and Little Belt attempted to bolt, but were overtaken and surrendered. Perry penned this line to General William Henry Harrison: "We have met the enemy and they are ours."

|

|

Stormed at by shot and shell |

|

|

Battle of Lake Erie |

< .

|

|

Barclay vs Perry on Lake Erie Battle at Put-in-Bay |

Lake Erie was lost to the long cannons that converted the British flotilla into sieves and floating wrecks. The battle was over before dusk. Captain Barclay's fleet fell to Commodore Perry's force. Perry accepted Barclay's surrender and made prizes of what was left of the captured British vessels. Perry's dispatch following his victory immortalized the man: "We have met the enemy and they are ours." This naval triumph on Lake Erie was not followed up by successful invasions over land, so once again the Americans made bold strokes that sounded better in dispatches than they did in deeds.

|

|

Battle of Lake Erie |

Captain Barclay subseqently informed his superior, Sir James Yeo of

"H.M's late ship Detroit, Put-in-bay, Lake Erie, Sept. 12, 1813."

Barclay began his report by reminding Yeo that he was obliged to sail the squadron "deplorably manned as it was" to fight the enemy because they were <b>"so perfectly destitute of provisions." As per Yeo's instructions, he was "to consult Major-General Procter, whose wishes I was enjoined to execute as far as related to the good of the country." As a result, battle was risked,"under the many disadvantages which I laboured" and he now had the "melancholy task to relate to you the unfortunate issue of the battle." He concluded his lengthy explanation with these words. "I trust that although unsuccessful, it may hereafter be proved that under such circumstances the honour of his Majesty's flag has not been tarnished."

Sir James Yeo, forwarded this note to his superior, Sir George Prevost.

"I yesterday received Captain Barclay's official statement of our ill-fated action on Lake Erie. It appears to me that though His Majesty's squadron were very difficient in seamen, weight of metal and particularly long guns, yet the greater misfortune was the loss of every officer, particularly Captain Finnis, whose life, had it been spared, would in my opinion have saved the squadron."

When Captain Barclay subsequently appeared before a court martial, his mangled figure brought tears to the eyes of spectators. He had lost one arm at the Battle of Trafalgar in 1803 and the second was so badly injured by grape shot that it required artificial support. His thigh was cut away so that "he tottered before the court martial like a Roman trophy." The following sentence was pronounced by the court. "That the capture of his Majesty's late squadron was caused by the very defective means Captain Barclay possessed to equip them on Lake Erie; the want of sufficient numbers of able seamen, whom he repeatedly and earnestly requested from Sir James Yeo; the very great superiority of the enemy; and the unfortunately early fall of the superior officers in the action. He was fully justified in bringing the enemy into action and during the contest was highly conspicuous and entitled to the highest praise. The court adjudges that Captain Barclay and his surviving officers and men be most fully and honourably acquitted."

While Barclay received a gift of plate from the inhabitants of Quebec and Canadian merchants in London, Upper Canadians had mixed emotions about the man. Despite Barclay's brave fight "those who knew of his leaving the blockade could not help feeling that all the disasters of the upper part of the province lay at his door." In 1813 the British Admiralty confirmed Barclay's rank as commander and in 1815 granted him a pension of 200 pounds in addition to the five pence he already received for his previous wounds. He was consigned to obscurity by the British navy and received no further employment before his death in 1837.

Perry gained great fame, receiving a vote of thanks from the Congress of the United States. He also received an instant promotion to the rank of captain and a gold medal presented by President Madison. Perry died of yellow fever while on duty in the West Indies in 1819.

Never again during the war was the British flag seen on Lake Erie. The loss of the British fleet on Lake Erie reduced General Procter to the necessity of abandoning all the occupied area beyond Lake Erie. American control of Lake Erie not only compromised Procter's own supply lines, it also left him vulnerable to attack, a plight made worse by the lack of reinforcements denied him by his immediate superior, Major General Francis de Rottenburg at Niagara. Procter, who never lived up to Brock's benchmark as a leader, concluded his only course of action was to fall back to Chatham some 100 kilometres inland from Amherstburg. This was not a bad decision but the coy manner in which his order was executed cost him considerable Native confidence and criticism from some of his offiers.

|

|

Tecumseh & Procter |

An outraged Tecumseh called Procter a coward, ranted and raved against his withdrawal and threatened to abandon the British forces. His impassioned pleas to stand and fight were for naught. Procter's view prevailed and the British abandoned Fort Malden. When the Americans invaded Amherstburg four days later Procter's forces began their slow retreat toward Chatham followed by their angry and disheartened Aboriginal allies. While Procter blamed their delay in reaching Chatham on the straggling families of his Native allies, he was careful to ensure that Tecumseh and his followers did not form the impression their families were being deserted.

Meanwhile Procter raced ahead to select the location of his stand against the Americans. The sight of his carriage disappearing into the distance was less than inspiring to the dispirited onlookers. Captain Adam Muir like several other officers of the 41st was contemptuous of Procter and said before the battle of Moraviantown that "Procter ought to be hanged" for his bizarre behaviour prior to the outbreak of fighting. Muir gave evidence at Procter's court martial.

|

|

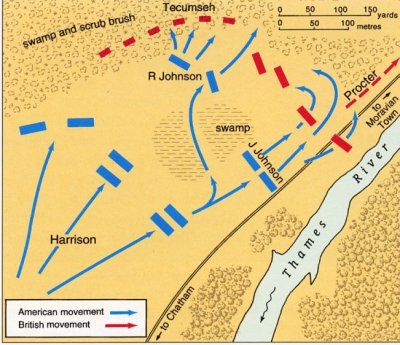

Moraviantown |

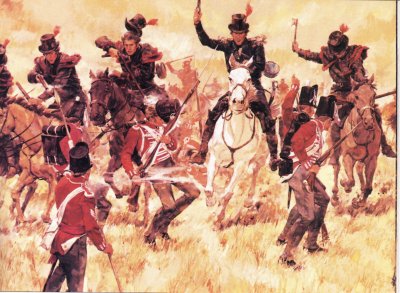

Procter favoured fighting at Moraviantown some thirty miles above Chatham and it was here on October 5th that he ordered his men to form for battle. The British regiment formed into a line extending some 230 metres to the right of the Thames river through an open wood to a small swamp. Tecumseh and his warriors formed forward of this small swamp along the edge of a much larger marshland. Here one thousand British and Native warriors faced three thousand Americans. The offensive began when a line of Harrison's snipers began taking a deadly toll on the thin red line. This was followed by the sudden charge of four columns of mounted Kentuckians. The rest is history. Here on October 5th the small force of hungry, harried and exhausted red-coated regulars was scattered at the Battle of Moraviantown by Harrison's larger army and his Kentucky sharpshooters.

|

|

Battle of Moraviantown |

|

|

Battle of the Thames |

|

|

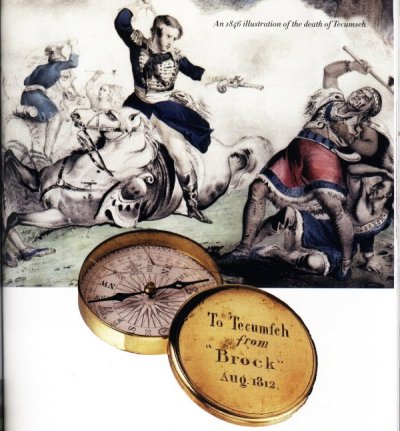

Death of Tecumseh on 5th October 1813 |

Unaware that the British lines had collapsed, Tecumseh and his warriors fought fiercely. Tecumseh's premonition that this would be his last battle was well founded. "Brother Warriors, My body will remain on the field of battle." Leading his fiery fighters in hand to hand contact, the great chief fell fighting from a mortal wound. Tecumseh's aide said the chief was killed by the pistol shot of Colonel Richard Johnson as he was charging Johnson with uplifted tomahawk.

|

|

Tecumseh Killed |

|

|

The Death of Tecumseh |

Tecumseh's Pocket Compass was given to him by Brock when they met to plan their celebrated attack on Fort Detroit. After Tecumseh's death at the Battle of the Thames on October 5, 1813, one of the chief's warriors requested that the compass be engraved in Tecumseh's memory. Brock would have approved.

Procter and a few survivors fled the scene retreating as far as Ancaster. Controversy followed the fleeing Procter when members of his own staff spread alarming accusations about his leadership. While the Commanders-in-chief Sir George Prevost and later de Rottenburg disassociated themselves from any responsibility for the defeat, hunger, fatigue and lack of supplies contributed to the British troops' failure to fight successfully.

In December 1814 a court-martial was held in Montreal where Procter faced five charges.

(1) He did not begin his retreat soon enough. (2) He allowed the retreat to be slowed by taking too much baggage, some of it personal.(3) He did not take care to ensure supplies and ammunition did not fall into American hands.

(4) He neglected to properly fortify his positon along the Thames.

(5) He failed to rally and encourage his troops and Aborigianl allies.

Procter was found innocent of the first charge but partially guilty of all the others, While suffering only a public reprimand and the forfeiture of pay and rank for six months, the sentence ruined his career. He died nine years after the battle at Bath, England. It has been suggested that Procter was a victim of circumstances, a brave but irresolute officer who was "simply unable to make the huge leap that distinguishes an average from an outstanding leader."

|

|

Procter |

The way was now open for Americans to attack the British forces from the rear in the Burlington-Niagara region. This never happened. For some reason Harrison failed to followup up his triumph and take full advantage of his victory. He torched the village and withdrew to Detroit while laden with loot and gory souvenirs his Kentuckians drifted homeward. Harrison's victory ended forever the Native threat to American settlements in the Michigan-Indiana region. Even though the American army withdrew to Detroit, the western part of the province was left exposed to American rampaging raiding parties which in the spring of 1814 came dangerously close to Port Talbot.

|

|

Caledonia |

[*] (From National Post Sept. 2009)

1812 WRECK AT CENTRE OF MODERN LEGAL BATTLE Rights contested for ship believed to be CaledoniaA 200-year-old Lake Erie shipwreck believed to be the Caledonia-- a Canadian-built brig that had a starring role in the first British victory in the War of 1812 -- is now at the centre of a legal battle between the State of New York and a group of relic hunters hoping to raise the vessel and make it a landmark attraction on the Buffalo. If it is the Caledonia lying off the shore of Dunkirk, N. Y., the 26-metre wreck -- said to be in superb condition by divers who have probed the site -- would represent a stunning historical find, just a few years ahead of commemorations being planned in Canada and the U. S. to mark the war's bicentennial. But North East Research -- a private U. S. group of Great Lakes explorers and filmmakers who have documented the wreck and claimed salvage rights --is facing an ownership challenge in a New York court from state heritage officials, the Buffalo News reported this week. The group has met with Erie County's top politician and other civic leaders about raising the wreck and creating a multimillion-dollar tourist attraction highlighting the region's rich War of 1812 history. Municipal officials are "very excited about the possibility of raising the historic schooner and turning this underwater treasure into a first-rate destination on Buffalo's waterfront," Grant Loomis, spokesman for Erie County Executive Chris Collins, said in an emailed statement to Canwest News Service yesterday.

"To be successful, this project needs broad-based support and financial commitments from various levels of government," Mr. Loomis said. "The county executive looks forward to continuing to discuss the possibilities of this project with his colleagues in government and North East Research." Divers have reportedly spotted human remains at the wreck site and retrieved some artefacts, including coins dated as late as 1834, when the decommissioned vessel was being used as a commercial cargo carrier. But it's the earlier phase of the ship's life that's tantalizing the researchers pushing to raise the wreck. The Caledonia was involved in three dramatic episodes during the War of 1812, and served on both sides of the conflict after being seized from the British in October 1812 during a daring midnight raid by the Americans. Built in 1807 at a Royal Navy shipyard near present-day Windsor, Ont., the Caledonia originally was owned by the North West Company and used for hauling furs from trading posts around the Great Lakes. It was pressed into military service when war broke out between Britain and the U. S. along the Canadian frontier in June 1812. Just a month later, the Caledonia carried some 400 troops -- a motley brigade of British and Canadian soldiers, conscripted fur traders and allied Indian fighters -- to U. S.-controlled Michilimackinac Island at the western end of Lake Huron, a strategic prize close to the eastern entrance of Lake Michigan.

Read more: http://www.nationalpost.com/news/story.html?id=1908247#ixzz0S3Q1n4EK waterfront. The following quotations pertaining to historical incidents involving the Caledonia are from the books underlined The War of 1812 p. 51Roberts embarked a small party of the 10 Foot (Royal Veterans) and with four hundred Indians alongside in canoes, he sailed over in the Northwest Company's fur-trading vessel Caledonia to Mackinac Island. Landing on its one practical beach on the northeast side, Roberts positioned a small gun on a rise overlooking the fort and called on the American garrison to surrender which they promptly did. p.72

One of the capable young Am officers, demonstrated their energy by travelling to Lake Erie and on Oct. 8, 1812, taking the armed British vessels Caledonia and Detroit - Hull's former Adams - in a "cutting out" expedition under the guns of the British post at Fort Erie, which stood where Lake Erie empties into the Niagara River. A naval yard was set up on that lake, at Black Rock, New York, a short distance from Buffalo. For Honour's Sake p. 127.

On the night of Oct. 8-9, rowing quietly in among the cluster of Br vessels tied up under the protective guns of Fort Erie, the sailors scrambled aboard two brigs, Caledonia and Detroit, cut them loose, took them under tow and started dragging them toward Buffalo. Although they managed to get the two-gun Caledonia away, the larger brig ran aground and had to be burned. As the lakes provided the most efficient means of moving men and supplies around Upper Canada, both sides knew that the initiative lay with whoever mastered their waters. p. 212

Perry also had eight smaller schooners, some built from scratch and others like Caledonia that had been captured earlier. p. 221

The next day, a Thursday, the British squadron sighted Perry's ships off Put-in-Bay. Aboard Lawrence, Perry hoisted a fighting flag bearing its namesake's dying, entreaty, Don't give up the ship." His squadron was strung out in a long column and two schooners, Scorpion and Ariel, in the van, then his flagship followed by Caledonia, Niagara, and the remaining four schooners in trail, Scorpion, Ariel and Caledonia all mounted long guns which Perry hoped would make up for the deficiency of guns aboard his bigger ships. The Naval War of 1812 p.100

A daring attack by Lieutenant Jesse Elliott, USN on 8 October, 1812, succeeded in cutting out the Provincial Marine's Detroit and Caledonia from under the guns of Fort Erie. The Detroit grounded and was burned but he succeeded in bringing off the smaller vessel. p. 116

The action commenced with a furious duel between the Detroit and the Lawrence, which crept ahead of her consorts and was soon drawing fire from the Queen Charlotte as well. Perry had instructed his second-in-command, Jesse Elliott, to take the third place in line in the Niagara behind the slow sailing Caledonia, which Elliott resented, but faithfully obeyed to the detriment of the Lawrence, for she was soon battered into a wreck with nearly 60 per cent of the crew killed or wounded. p. 130

Early in June 1814, Madison's cabinet decided on its objectives for the summer campaign which was to recapture Mackinaw and destroy a Royal Naval base said to be under construction on Georgian Bay. By mid-July with 1000 soldiers aboard the brigs Lawrence, Niagara and Caledonia and the schooners Tigress and Scorpion, they set off. They burned the abandoned British fortress on St. Joseph, captured a pair of small lakers and steered for Mackinac arriving there on 26 July. After some brief, but deadly exchanges, the Americans retreated and the attack ended. Sending the Lawrence and Caledonia back to Lake Erie with the 70 casualties suffered in the fighting, Sinclair returned to Georgian Bay in search of another fur trading vessel, the schooner Nancy. [*] An engraving from a portrait by Alonzo Chappel fron 1812 The War No One Won, by Albert Marrin, Atheneum 1985 New York

[**] painting by C.W. Jeffreys, courtesy Library and Archives Canada C-70396)

[***] British ships gun/tonnage taken from Naval Occurrences of the War of 1812 by W. James, Conwary Maritime Press 2004

Copyright © 2013 Website Administrator