foreword | Historical Narratives | Resources | Links | Contact

THE HAMILTON AND THE SCOURGE

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Foreword | Historical Narratives | Resources | Links | Contact |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

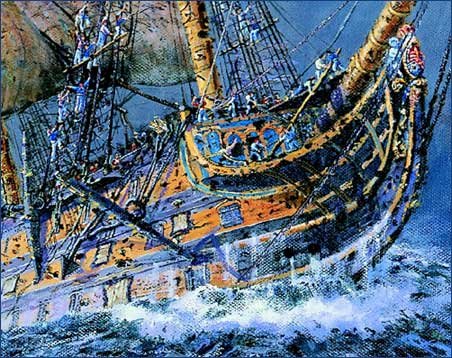

WAR OF 1812 History is at once a tale of intrigue and bloodshed. The Age of Fighting Sail "It is not ships that win battles it is men." About ten kilometres off Port Dalhousie in the cold, clear depths of Lake Ontario two perfectly preserved vessels lie in the clay silt 89 metres down. [See Below *] Separated by some 461 metres, the ghostly schooners await the day when they will be raised and their entombed dead returned to the United States' Navy for burial with military honours. When the ships are rescued finally from the frigid waters in which they have lain for 192 years, the historical treasures will be displayed on a five acre site in Hamilton near the Queen Elizabeth Way. The province which owns the lake bed has given the wrecks to the city. [**]

The two vessels, the Hamilton and the Scourge, last saw the surface and service on August 8th, 1813. They were part of

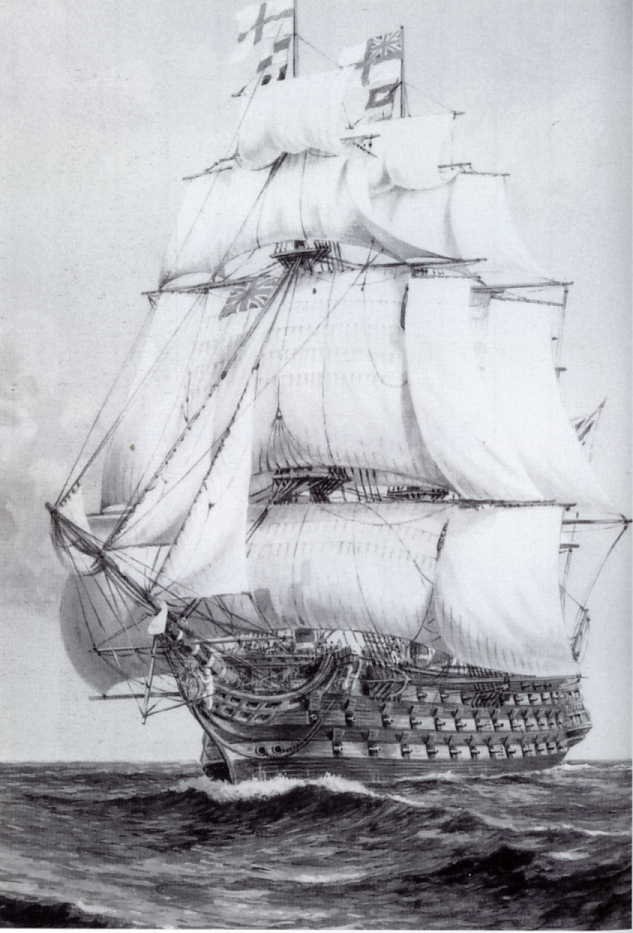

On 19 March, 1813, Sir James Yeo was appointed commander of the British fleet and his "first and paramount" objective was the defence of the North American provinces. Yeo arrived at Quebec on May 5, 1813, to take up his command as Admiral of the Lakes. He was born in 1792 and had joined the navy at age 11. Subsequently he became a naval hero who had served with distinction under Lord Horatio Nelson. Yeo had once captured a French privateer and a fortress with only fifty men in a lightning raid on the Spanish coast. Recognized as a bold practitioner of unconventional sea warfare, Yeo rose rapidly through the ranks and received knighthood in 1810. The British commodore now commanded two ships, the 23-gun Wolfe and 20-gun Royal George, two brigs, the 16-gun Earl Moira and 14-gunLord Melville and two schooners, the 12-gunLord Beresford and (12-gun)Sir Sidney Smith. The American squadron was commanded by Commodore Isaac Chauncey, a tall, portly, pompous person, who was always very certain of himself. The forty-year old Chauncey, who had fought pirates off the shores of Tripoli, was considered by some to be the best officer in the United States Navy. At the end of 1812 Chauncey had boasted to a colleague: "I am happy to have it in my power to inform you that I have now the command of Lake Ontario." The American naval force comprised thirteen sail: two ships, Chauncey's flagship, the 26-gun General Pike and the 24-gunMadison, the 18-gun brig, Oneida and ten schooners. Anchored off the mouth of the Niagara River, Chauncey's squadron prepared to engage the British squadron in their first face to face conflict Most of the British ordnance (weaponry) compromised carronades of which they had seventy-eight. Yeo, who had only 19 long guns to contend with the long-range capability of the Americans, said this required the British "to engage them at close quarters and board, which depended on having the wind in our favour as to be enabled to maintain a distance or come close to action." Chauncey's goal was to remain out of reach of the British carronade, while pounding away at his enemy with long guns, especially the 24-pounders on the Pike. Manoeuvring at sea was no easy task. On land the battlefield is stationary and the troops move. At sea the ships change their relative positions very gradually, while the battlefield rushes past as fast as horses can gallop. The day before the British squadron with Sir James in the flagship Wolfe had raised sail and in a gentle morning breeze on a rolling swell, departed from its base at Kingston. While Yeo's record was impressive, his service on the lakes lacked any evidence of extraordinary acts for he failed to follow Nelson's first rule of conduct: "No captain can do very wrong if he places his ship alongside that on an enemy." In other words, engage the enemy.

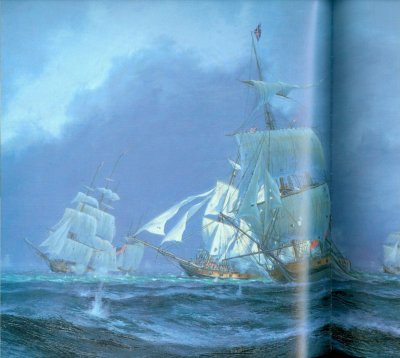

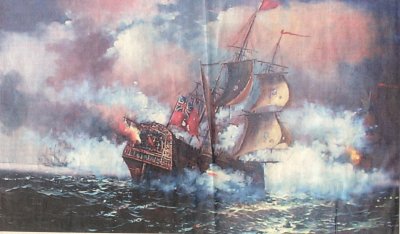

The thirty-year old Yeo was a dark-haired, intense man with a jutting jaw and determined mouth. He was a private, moody individual whose behaviour ranged from hesitant uncertainty to impulsive, short-tempered activity. These characteristics were reflected in his leadership on the lake. He had never commanded a squadron prior to his appointment as commodore and his orders stipulated that he was not to undertake any operations without "the full concurrence and approbation" of Sir George Prevost. Governor-in-chief of British North America, with whom Yeo had a somewhat aloof relationship. Notwithstanding his own inclination to avoid confrontation, Yeo found Prevost's cautious indecision frustrating, a criticism shared by many of Prevost's other officers. During Prevost's unsuccessful assault on Sacket's Harbor, Major William Drummond, a rashly brave and inspired leader who was worshipped by his subordinates, refused to surrender and pleaded with Prevost, "Allow me a few minutes, Sir and I will put you in possession of the place." Prevost retorted angrily"Obey your orders and learn the first duty of a soldier." When the bugle sounded retreat, many of the British soldiers misunderstood its meaning and responded with long cheers. Then realizing that it meant retreat, they bitterly obeyed. It was expected that Yeo, who was given the nickname, "British knight," would make short work of Isaac Chauncey's naval squadrons and quickly assume supremacy on Lake Ontario. Earlier Yeo's arrival at Kingston with 448 seaman, gunners and marines had caused great excitement, "raising the drooping spirits of the inhabitants of that place and generally of the country at large." Yeo had come straight from a court-martial called to consider the loss of his ship Southampton on a reef in the Bahamas. After being acquitted of negligence, he was immediately dispatched directly to Canada. The Americans spotted the British squadron some five miles distant. Both commodores sought to gain the wind's advantage but light airs prevented their engagement. Both Yeo and Chauncey claimed they were anxious to fight but managed by evasive manoeuvring to maintain a safe distance from each other. They largely avoided carrying the contest through with cannon except for a few indecisive skirmishes like the one depicted below which took place on Lake Ontario in September 1813.

"The two naval heroes were fearful of defeat, each holding the other at little more than arms length with neither willing to risk a battle without a decided superiority in guns and men." Neither man was willing to expose his ships to the hazards of hostility. Frequently after shadowing one another for several days, a providential breeze saved them from having to confront each other. It was charged that Chauncey was prepared to abandon any American field forces rather than risk his fleet in combat. Yeo was every bit as protective of his ships and his reluctance to venture out with his vessels appears in his various letters to superiors. When Sir Gordon Drummond asked Yeo to support a military engagement with his squadron, Yeo's response written on his flagship HMS St. Lawrence on the 19th October, 1814 clearly indicated his his aversion to risking vessels in any contest with the enemy. Even when his naval force was superior in size to that of the American squadron, Yeo used his assumption of government policy as an excuse to do nothing as indicated in this letter dated June 3rd, 1814. The American president James Madison blamed the lack of any conclusive engagement between the two men on "the caution of the British commander who frustrated the efforts of Chauncey to bring on a decisive action." According to Madison Chauncey had "established an ascendancy on that important theatre (Lake Ontario) and wanted only the opportunity for a more shining display of his own talents and the gallantry of those under his command." In fact, Chauncey himself chose not to expose his ships to the menace of a showdown and not occasionally, set every scrap of fabric on the foremast to make a speedy exit. Lord Horatio Nelson's defeat of the French and Spanish navies at Trafalgar on October 21st, 1805 [*****] had left Britain mistress of the seas.

In 1812 the Americans declared that this supremacy had passed to them. They had become the "descendants of the sea rovers who had commenced to build a great empire in the Western Hemisphere." Sentiments of a similar nature were indicated in this toast given at a formal dinner attended by the president and his cabinet on July 4, 1812. "To an infant Hercules destined by the presage of early prowess to extirpate the British race of pirates and free-booters." Other Americans were a little less certain, decrying this crazy crowing and describing the American navy as being so "lilliputian that the British Gulliver would bury it in the deep." Numbers seemed to suggest there was a real likelihood of this happening, for to face the British fleet of 600 men-of-war that included some 250 ships-of-the-line, the United States navy consisted of 20 ships, ten of which were frigates and the remainder a ragged assortment of smaller vessels and largely useless gunboats. Madison in his message to Congress claimed that because of the caution of the "elusive Yeo," the Americans were unable to corner and capture the British "knightly foe." After the war Yeo commented that Britain owed much to "the perverse stupidity of the enemy." A sudden and decisive sea battle could put a premium on intelligent, courageous leadership but that kind of leadership was lacking in this instance. Intent on keeping from being killed or captured, both frequent faults of war, the two men blamed the weather for their frustration at not being able to close and clash. Chauncey said he failed to find opportunities to make energetic use of his superior long-range guns, while Yeo cursed the contrary winds that prevented him from getting close enough to make effective use of his deadly, short-range carronades. Both men were determined not to hazard the fleet. This shorfall of fighters condemned their vessels to ghostly inactivity. They persisted in playing a game of tag till the end of the war, always carefully avoiding a head-on conflict. Chauncey explained his reluctance to risk all in a fight to the finish by stating that if he were fighting at sea and was defeated all he would lose would be a ship or perhaps even his fleet. In this instance, however, if he lost his fleet on the lakes, it could cost him his country too. Wooden ships of war operate by harnessing the wind and on the afternoon of August 8th it suddenly ceased to blow. Neptune, the god of the sea, silenced the wind and the waves producing one of the several calms that fell upon the lake during that hot, sultry summer. With flags limp and sails sagging in the stifling heat on the glassy lake, the cautious combatants found themselves unable either to fall upon or to flee from one another. The calm continued until sunset when darkness descended and silence settled over the broad waters. The American ships lay at the western end of the lake some distance from the British squadron to the north. The Hamilton, formerly an American merchantman named Diana, that was built at Oswego in 1809 had been re-armed and renamed. Two months earlier the Scourge, which had also borne another name, had likewise been employed on more peaceful pursuits. Construction of the 18-metre schooner by shipwright Asa Stanard had commenced on October 1st, 1810 and was launched on May 1st, 18ll at Niagara (Niagara-on-the-Lake). It was the principal vessel of the shipping firm W & J Crooks, a profitable Niagara trading company that provisioned the military and carried grain, flour and potash to Lower Canada. The schooner was christened Lord Nelson and bore on its prow a proud likeness of Admiral Horatio Nelson, Britain's greatest naval hero. The striding figurehead while handsome was historically inaccurate for its sculptor had carved the hero's image with two arms, forgetting that 15 years earlier Nelson had lost his right arm for which the heroic seaman had received a pension of 1000 pounds.

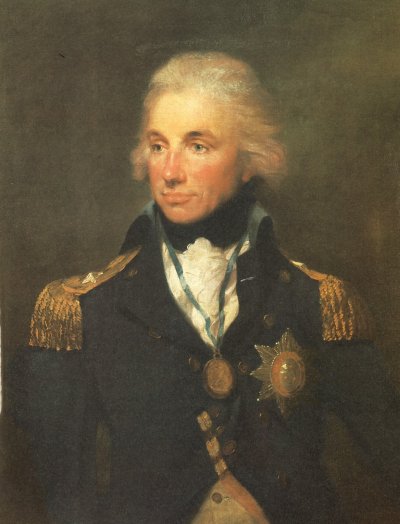

Nelson had an unusually clear mind, a keen intellect and an insatiable thirst for glory. Not much over five feet tall, he was a slight, battered-looking individual who had given an arm and later lost an eye in the service of his country.

Nelson was vain, reckless, arrogant and always dressed to kill or be killed, for whether on parade or the poop deck he jangled with decorations. Nelson was prematurely grey and had no teeth but in every way that counted he was larger than life and in death he became renowned. He was pacing the pitching black deck the night before the battle that bestowed on him eternal rest and priceless immortality. His demise in the hour of a crushing victory left a valiant memory which time has never dimmed.[****] The War of 1812 in which James Crooks participated as an officer in the Lincoln Regiment pretty well destroyed Crooks' Niagara business operations. His ruination commenced on the fifth of June when as his schooner, Lord Nelson, was travelling from Prescott to Niagara, it was pirated by the 16-gun brig U.S.S. Oneida, the only American vessel then on the Great Lakes. Lord Nelson was commandeered and immediately sailed to Sackets Harbour where it was converted into an armed warship and re-christened Scourge. The conversion of this vessel was the first task undertaken by a master Scottish shipwright named Henry Eckford. Eckford, who learned the trade at his uncle's shipyard in Quebec, later moved to New York where he set up his own shipyard. He came at the call of Commodore Chauncey to lay out a shipyard at Sackets Harbour where he began to design and build ships of war. The winter of 1812-13 was bitter and the men building ships on both sides of the border worked in snow and biting cold. Discontent was constant among civilians, sailors and soldiers alike, but Eckford was a leader as well as a talented shipbuilder and able to inspire his workers.

The Scourge's bulwark had been raised and planked and armed with six-pounders on conventional carriages. A 32-pound cannon was located amidships on a pivot. Eight 18-pound carronades were also included. Originally called "the smasher" this short-barrelled, short-range weapon had more explosive power and its charge could propel a heavier ball. Measuring a little over four feet, it occupied less deck space, was more mobile and could do tremendous damage to an opponent, but it was limited to close range combat. Carronades could also fire canister, small, iron balls packed in a large tin can which burst when the gun was fired spraying the balls across the enemy's deck.

The carronade was intended as an auxiliary weapon not a ship's primary armament. Its use as the main weapon was a weakness of the British ships and this was revealled in combat with the Americans. Longer guns enabled the captain to damage the enemy before the carronades could be brought into use. Both types of guns were muzzle-loading with the ball being inserted into the end it came out. The gunpowder encased in a cloth or paper bag was also called a cartridge and contained the right amount of black powder for the weight the iron ball to be fired. The calibre of the cannon - 'the long gun' - was based on the weight of the shot it fired. These ranged from 4-pounders to 32-pounders. The cannon could measure ten feet in length and weigh as much as 6500 pounds. Each could require a crew of as many as 14. With a charge of black powder equal to one third the weight of the shot, the cannon depending on its elevation, could propel a 32-pounder more than 1000 yards smashing sides and scattering huge splinters that were as deadly as shot itself. The carronade weighing 2000 pounds required a crew of seven men and could fire a 32-pound canister effectively at a range of 500 yards.

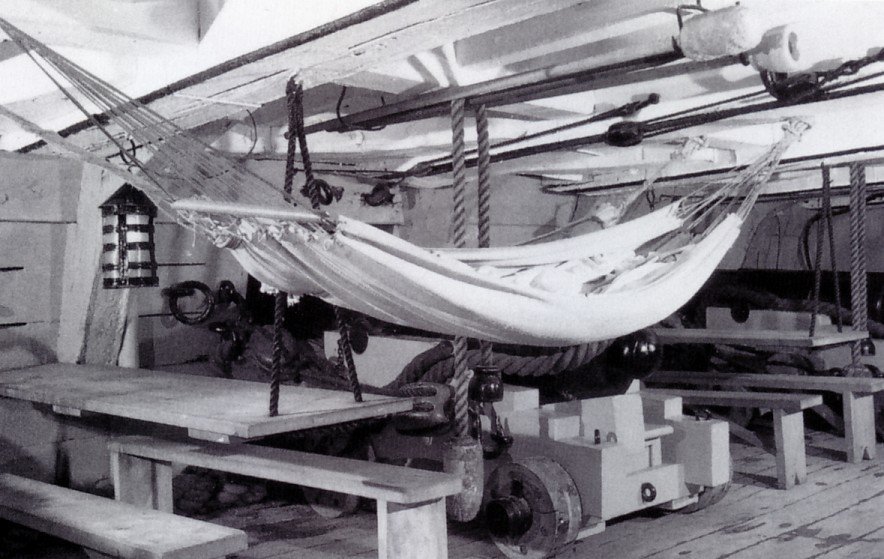

The rapidity of fire of a gun crew of five depended on how well they worked together. The "exercise of Scourge's guns" consisted of loosening the gun from its lashing and removing the tompion, a wooden plug from the muzzle of the gun. To load a cannon the loader pushed a flannel bag of gunpowder down its bore, followed by the shot (cannon ball) and a wad to prevent the shot from falling out. This was rammed home tightly. Next the "gun was run out," care being taken to properly arrange the ropes by which the gun was secured so as not to be foiled on the recoil. A cartridge of powder was opened and plunged down the touch-hole in the top of the cannon to prime the gun. The cannon was then pointed or aimed. The gun's captain fired it by applying a slow match to the touch-hole then leaping clear of the recoil which returned the gun to its loading position. The gun was sponged to extinguish any remains of the fire and the process quickly repeated. A 42-pound shot was the largest a man could reasonably load on board ships in action. The ammunition for all these cannons was a solid, cast iron ball of various diameters. This ball had the greatest range of any ammunition and was often heated red hot in a shot oven, an iron box on wheels burning charcoal. The heated ball set wooden ships and forts on fire. Chain and bar shot in which two balls were connected by a chain or bar were also used especially in the navy where they could tear rigging and sails. Small arms including muskets, pistols, boarding pikes, axes and cutlasses were also available on board for use in close combat when boarding another ship. The cutlasses had straight blades, iron, figure-eight guards and cast iron grips. Two of these cutlasses were located over each gun port. Although schooners converted by both sides produced a rapid increase in fleet size, they were less than successful as fighting ships. The addition of all the firepower made the vessel dangerously top-heavy. The weight of the weapons severely strained the ship and the high centre of gravity caused by the guns made the vessel exceptionally unstable when heeling and it became almost unmanageable in a blow. "It was a lovely evening," recalled Seaman Ned Myers, one of the eight surviving members of the crew of the Scourge. "Not a cloud was visible and the lake was smooth as looking glass." Dusk descended across the broad lake sky merging the heavens and water into darkness, Night time brought rest for the tense seamen, who ate, slept, fought and died between the decks along side their brute cannon. They welcomed the captain's order to splice the main brace, a nautical expression meaning to give each man a ration of rum. The 50-man crew of the Scourge ate supper then collapsed near their cannons and using shot boxes as pillows slept soundly. Both vessels had earlier provided fire support for the assault on the town of York and Myers lay on a rug he had taken as one of the spoils of war. It was said that "there is not a more ferocious sea in the world than Lake Ontario whose storms were far more dangerous than those on the Atlantic coast." Chauncey soon learned how very true this was when two of his schooners drifted off as blackness descended over the scene. All was quiet on the moderate lake and the pitching horizon was empty except for the ragged edges of steely gray clouds. Suddenly on August 8th shortly after midnight, a black squall arose with winds that lashed the deck catching the crews ill-prepared because the sails had not been reduced at sunset. Lightning scared the sky and thunder echoed across the lake as torrents of rain pelted the little ships and gale force winds whipped huge waves across their shivering bows. Not even the crashing thunder could drown out the shrieks of the terrified men on the Scourge as the little vessel leaned crazily on its starboard side, its soaking canvas sails buffeting wildly in the wind. Under the stress of gale-force gusts the ship creaked, groaned and heaved like a living thing. As thunderbolts lit the dense darkness, the vessel was smashed by the hammer-blows of the waves that exploded over its bow filling the ship to overflowing. Within minutes of the onset of the storm, the vessel tilted sharply and slipped beneath the raging water. Only eight seamen survived. For the remainder the Scourge had become what some had said it would - a coffin. A similar number survived from the Hamilton which also sank. These were two of Chauncey's best schooners.

It was an inauspicious debut for Chauncey for on the 10th Yeo captured two more schooners that had strayed from the American line. One of Chauncey's officers angrily complained in a letter home, "This is only part of the evil arising from not attacking the enemy on the third, for which the Commodore is answerable and perhaps highly censurable. (You know he is a peace man) ... .)" Britain managed to maintain mastery of this lake and the St. Lawrence River until the end of the War of 1812.

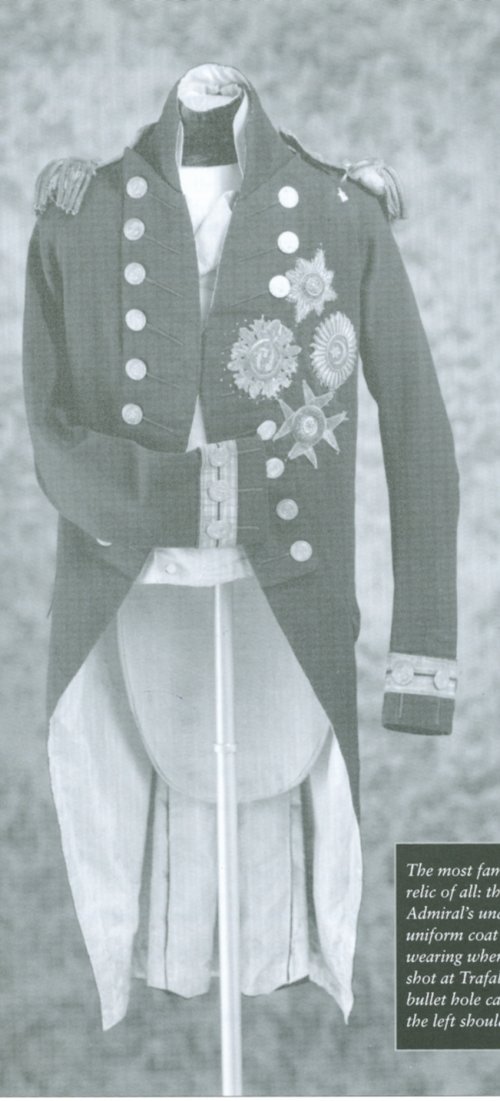

[*] In 1975 the two schooners were discovered at the bottom of Lake Ontario whose average depth is 31 metres and greatest is 240 metres. The location of the Scourge and the Hamilton was declared a national historic site in 1980 and the ships were given to the city by the province. Canadian authorities have been urged for years to raise the vessels and preserve them in museums. The city has been warned that the ships may be threatened by deep-water zebra or quagga mussels or by the dragging anchors of large ships. The United States has offered to pay the multi-million-dollar cost to bring them to the surface, but Hamilton turned down the offer, because one of the wrecks would have gone to a U.S. museum. [**]Unauthorized attempts have been made by divers to visit the sunken warships, the latest occurring in July 1997 when several men were prevented from doing so by police and Canadian Coast Guard vessels. The would-be divers had no permit and faced a fine of $50,000 or a year in jail or both if they dived. In July 2004 it was announced that to preserve the only two completely intact War of 1812 vessels in existence, heritage officials would instal an underwater "burglar alarm" to protect the 200-year old "time machines" on the bottom of the lake from looting souvenir hunters. The radar system, which can sweep almost the entire western half of Lake Ontario, is sensitive enough to detect a rowboat on the lake and its sensitive signal software can dispatch within minutes a police boat to investigate any suspicious craft. [****] Always one to lead the fight and push ahead into the enemy, Nelson was a genius as a naval commander and no one was more convinced of that than Nelson himself. God-kissed talent is normally reserved for great artists but Nelson's career, talent and self-promotion made it applicable to a military man too. His well-known vices of vanity, recklessness and arrogance were sold as part and parcel of his greatness. Like Wolfe he designed his own transformation into immortality. [*****]The Battle of Trafalgar was joined shortly after noon. Four and a half hours later on a warm afternoon of light winds it was all over. A French and Spanish fleet of 33 ships-of-the-line had been savagely and utterly defeated with some 4500 dead by a slightly smaller but more effective British Fleet commanded by Lord Nelson. Nelson was on the French hit list and was struck down by a bullet fired by a marksman in the mizzentop of the 74-gun Reboubtable while she was locked alongside the Victory.

Nelson refused to wear a plain coat so four glittering stars provided a perfect bull's eye. Having led the way through a hail of shot the Victory became entangled with this smaller French ship and it was from her rigging that the bullet was fired which struck Nelson at about 1.15 p.m. as he was pacing the quarterdeck. It hit him in the left shoulder, drove downward into his chest tearing through his left lung, severed a major artery and fractured his spine.

Carried down to the cockpit below the Victory's waterline where the wounded were treated in comparative safety, Nelson lingered in great pain long enough to learn that he had won a decisive victory. The log of Victory said simply: "Partial firing continued until 4:30 when a victory having been reported to the Right Honourable Viscount Nelson, K.B. and Commander-in- Chief, he died of his wounds."

The musket ball which was extracted from his spine after his death is displayed in Windsor Castle. On it are traces of the gold filament which was picked up by the ball as it passed through his left epaulette on its fatal path. When he learned the French forces had been defeated, Horatio Nelson's last words were, "Now I am satisfied. Thank God I have done my duty."

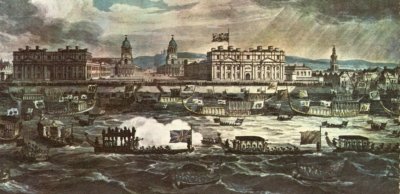

[*******]Nelson's body was placed in a barrel because there was not enough lead on HMS Victory to make a coffin. To preserve the body for the lenghty trip, the barrel was filled with brandy. Once it arrived at the Thames estuary, the body was removed from the shattered hulk of the Victory at Greenwich for an autopsy. It was then placed in a lead coffin and borne in state to be viewed by ordinary sailors and the common people whose love he cultivated and for whom he genuinely cared. Rejoicing at Nelson's remarkable victory was overshadowed by grief at his loss. A midshipman Joseph Woollnough recorded that when his comrades heard the news "A stranger might have supposed from the gloom that spread among them that they had been beaten instead of being conquerors." There was a similar mixed reaction in Britain. As Robert Southey, the Poet Laureate, later recalled in his Life of Nelson published in 1813, "The victory of Trafalgar was celebrated, indeed, with the usual forms of rejoicing but they were without joy."

Nelson's funeral took place at St Paul's Cathedral. The funeral was a great state occasion which overshadowed Prime Minister Pitt's which took place a month later. It also outdid royal ceremony for it was designed to fill the country with deep patriotic emotion. Nelson's service and sacrifice have been remembered ever since.

Nor could military superiority conquer an opponent who refused decisive battle.

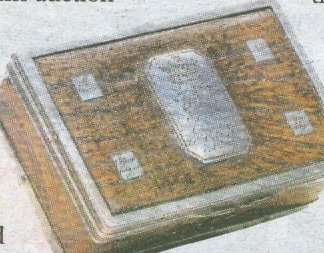

[*******]A box said to be made from wood used to bring home the body of Admiral Horatio Nelson from the Battle of Trafalgar, sold for 8,160 pounds. The box itself is said to have been made from wood from the brandy-filled barrel in which Nelson's body was kept on the voyage home, or from part of a wooden coffin that briefly encased the remains before burial. A silver plaque insde the box is inscribed: "This wood once contained his sacred remains." Small medallions on the lid are inscribed "St. Vincent," "Nile," "Copenhagen," and "Trafalgar," in reference to his victorious campaigns at the Battle of Cape St. Vincent in 1797, the Battle of the NIle in 1798, the Battle of Copenhagen in 1801 and Trafalgar in 1805. Prior to the start of the battle of the Nile, Nelson said, "Before this time tomorrow, I shall have gained a peerage or Westminster Abbey." He was right and wrong; he got his peerage, but St. Paul's Cathedral.

29 September, 2008 marked the 250th anniversary of Horatio Nelson's birth. He was born on a Sunday. To celebrate this occasion, a bust of Nelson was unveiled to mark the event. The life-sized bronze is now on show in the officers' mess at HMS Nelson, Portsmouth Naval Base the BBC reported. Among those present were Nelson's oldest living descendant, Anna Tribe and Vice Admiral Alan Massey, the Second Sea Lord. The bust was created by sculptor Robert Honryold-Strickland after being commissioned by an anonymous donor. Mr. Hornyold-Strickland wanted a realistic representation of Nelson as he would have looked at the time of the Battle of Trafalgar. He therefore based his work on the life mask of Nelson produced in Vienna in 1800, "having satisfied myself that the mask was the best likeness I could get."

The following paintings are the work of

[*]

The Standard, Saturday, April 17, 2010 Copyright © 2013 Website Administrator |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||