foreword | Historical Narratives | Resources | Links | Contact

History deals with the world man has fashioned for himself.

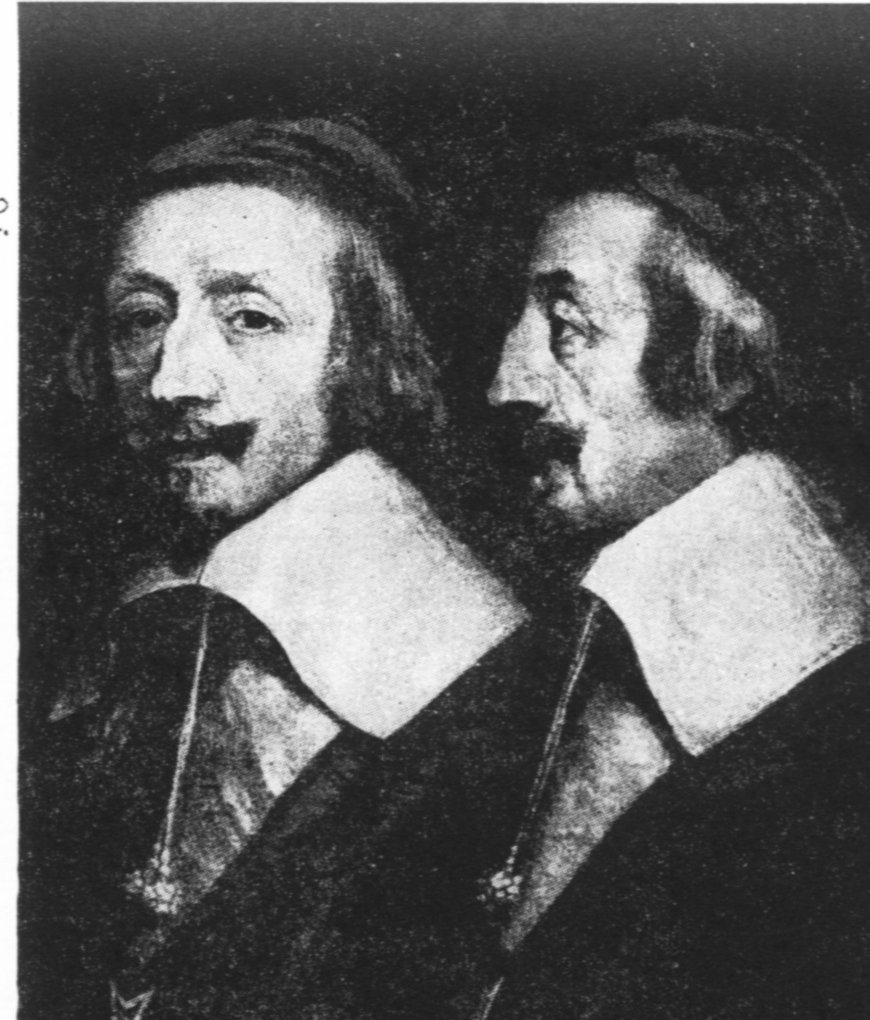

SAMUEL DE CHAMPLAIN

|

|

"With a statue, it is the stone that is not there that matters". |

The curtain across the continent of North America was partially parted by John Cabot in 1497 and more of the land mass was exposed by Jacques Cartier's exploration in 1534.

|

|

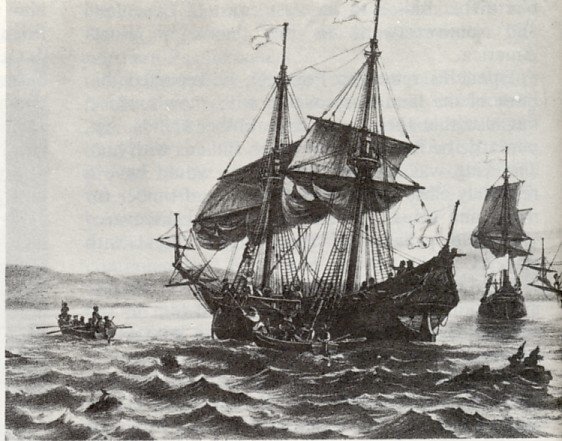

Replica of Cabot's Ship Matthew |

|

|

Jacques Cartier's Arrival at Quebec |

|

|

"In Champlain alone was the life of New France." |

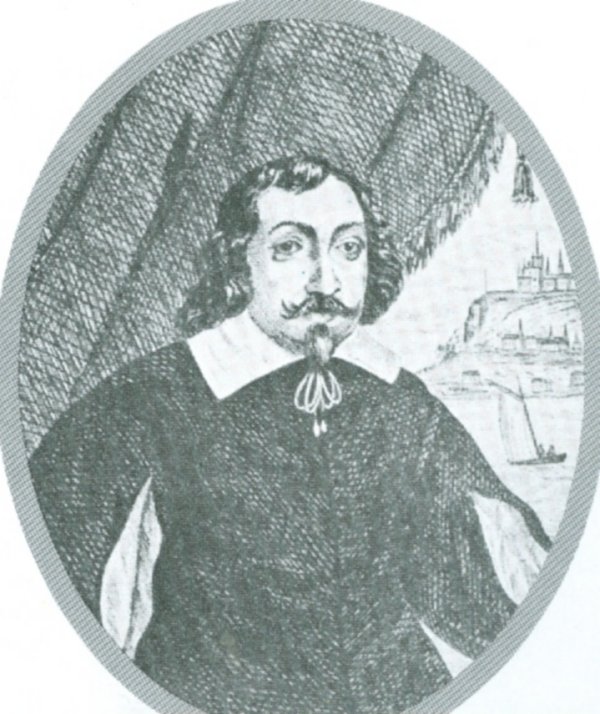

He called himself, "Samuel Champlain de Brouage," and told Henry IV of France personally about his travels. He established Port Royal but abandoned it for a promontory on the St. Lawarence which he called Quebec. He lost the colony to the English, regained it and died there on Christmas Da, 1635.

At the beginning of the 17th century, France began to focus its attention on that part of the new world known as Kannata, the Huron-Iroquoian word for 'town'. In 1603, Francois Grave Depont was dispatched on an expedition to explore this primitive place and Samuel Champlain was invited to go along.

Little reliable information exists about Samuel de Champlain's pre-Canadian career. He was a slight, spare, dark-skinned man with eyes that endlessly scanned the sea that was to become his life. Samuel was born of a seafaring family in Brouage,[*] a fortified town north of Bordeaux on the Bay of Biscay facing the Atlantic Ocean. Apparently the Champlain family had three houses there, but the one in which Samuel was born is unknown. The town's birth records were lost in a fire, so the date of his birth is unknown. Some records suggest he was born in 1567.

|

|

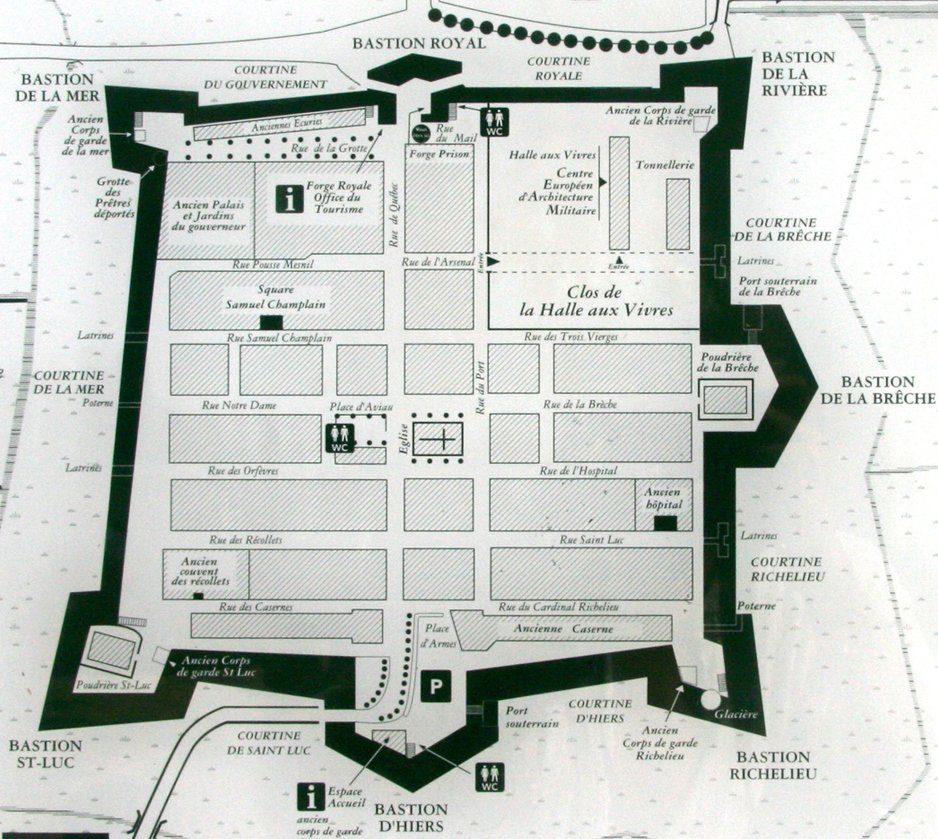

The Citadel of Brouage |

|

|

Citadel of Brouage [#] |

|

|

Wall of the Town of Brouage |

|

|

Monument to Champlain in Brouage |

The son of Antoine de Champlain, Captaine de la Marine, Samuel came by his nautical knowledge from his father from whom he acquired a mastery of the arts of map-making and navigation. While neither peasants nor a noblemen, the Champlain's possessed sufficient social standing to warrant the use of de.

Champlain reached maturity in an age of blood and iron and caught his first glimpse of America when he crossed the Atlantic with a Spanish fleet in 1598 as captain of the Saint Julien. After visiting Puerto Rico, Mexico and Cuba, he returned to Spain, capturing two English vessels en route. He was both a Catholic and a King's man and although having neither wealth nor rank, Champlain was recognized by Henry IV and appointed Geographer of the King in 1601.

|

|

Door of Americas [#] |

Since the XXVIIth century, this doorway from the citadel of Brouage has led to long days of danger on the sea. Among those passing through this portal was Samuel de Champlain, whose name became famous as the founder of Canada.

|

|

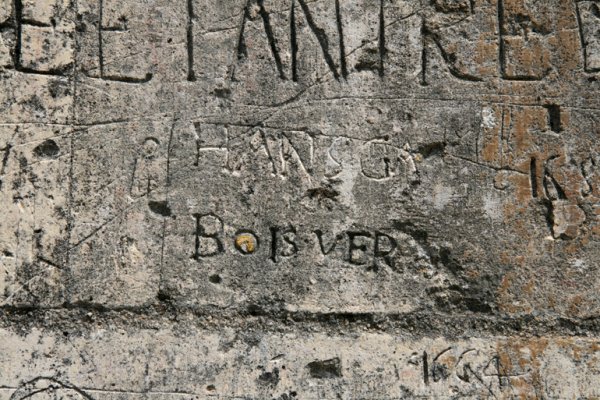

-Graffiti and names line the wall leading from the Fortress.[#] |

Since early times, the soft limestone in this area of France was widely used in architecture. Its impressible nature naturally attracted amateur artists, soldiers, sailors and simple lovers whose scratchings scared its surface.

|

|

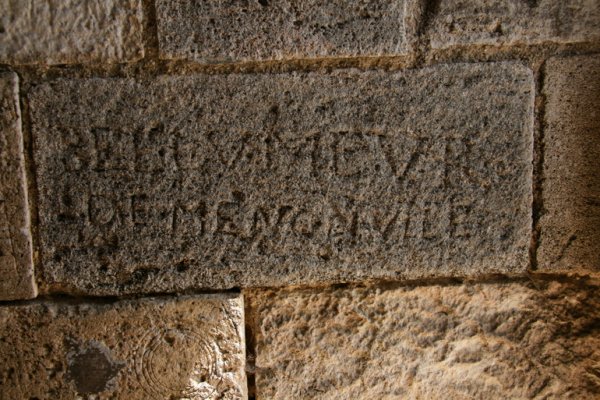

Names saved for the centuries.[#] |

Names, perhaps, of sailors and soldiers, who facing dangers and death in distant lands, decided to notch their names in the soft limestone, touching testimony to their having passed by this way. Wind, weather and tourists intent on making their own mark here, threaten the loss of these intriguing trademarks of patrimonial pride. [#]

|

|

Could they have come to Canada with Champlain? [#] |

|

|

One of the stained glasses of the church of the town of Brouage towards whose cost Canada contributed.[#] |

The two figures honoured on this beautiful window are Samual de Chammplain on the left and Paul Chomedey de Maisonneuve, the founder of Ville-Marie](a religious mission in what is present day Montreal) on the right. Faced with fiercesome attacks on the tiny settlement by Iroquois, Maisonneuve, a devout thirty-year old army officer, whose piety was matched by his courage, demonstrated great leadership in Montreal for a quarter century.

|

|

Monument Maisonneuve at Place d'Armes, Montreal |

When he accompanied De Monts in 1603, Champlain had no offical capacity, but went along as a private passenger, although he was a talented draftsman and painter by profession. His presence as a mere observer would have been hidden from history except for the fact, that he kept an account of the trip which he published. It was the only written record of the voyage.

In addition to visiting Tadoussac, where he observed "tabagies" (native feasts), Champlain travelled up the Saguenay and learned about a salt-water sea to the north, from which he divined in some fashion the existence of Hudson Bay. He also ascended the St.Lawrence as far as the La Chine Rapids.

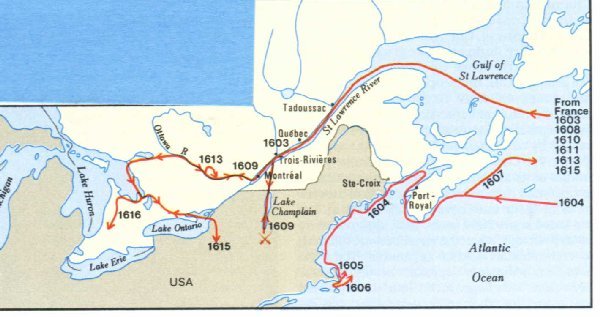

In March 1604 Champlain embarked once again with Sieur De Monts for America. They established a settlement at Port Royal (now Annapolis Royal, Nova Scotia) and explored the seaboard from Cape Breton to Martha's Vineyard. Champlain sailed back to France in 1607.

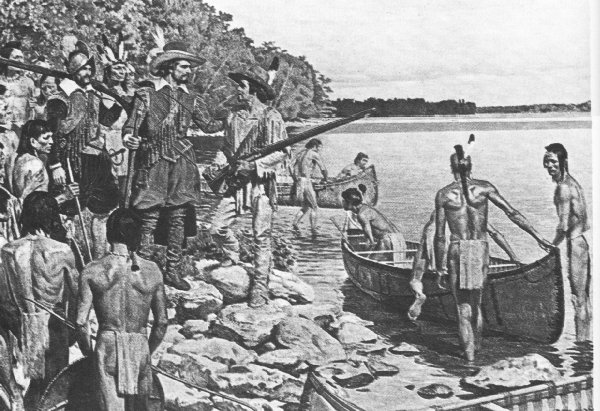

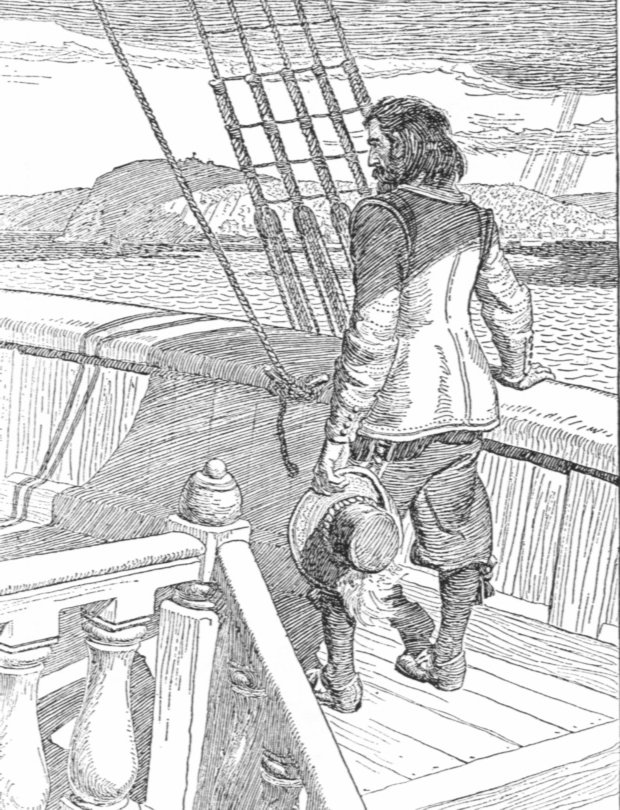

In 1608 Champlain returned to Quebec and sailed once more up the majestic river, until he reached the spot where through the solitude and silence of the ages, a huge crag thrust its rocky ridge into the raging current. Aboriginal warriors watched his ship in wonder and amazement as the floating fleck on the water loomed ever larger. Reaching land at last, Samuel de Champlain stepped ashore on Sunday, July 3rd in 1608 to face the fiery folk gathered round about the great rock.

In that year, on that day, from that hour, dates the commencement of the continuous story of Canada.

|

|

Champlain Arriving at Quebec |

Champlain's curiosity and enterprise served trading companies and the monarchy, but he saw beyond their narrow focus on finances to the vast, fair land of forests, rivers and lakes he grew to love. He declared the farther they went, the more beautiful was the country, which he called, "a new world fair to perfection."A builder with an impulse turned outward, not inward, he as an active not a contemplative person, whose curious mind was always seeking some new unknown.

Disdainful of resting by the river, Champlain sought to open the vast, heavily-forested, intricately-watered dominion, whose many hazards made "life the more delightful." To this individual, whose followers fostered discovery and trade that spanned the continent, fell the glory of being the father of a new nation. Eager at any cost or discomfort to seek, to see, to look at and love, we salute the founder of our great country Canada - Samuel de Champlain.[**]

|

|

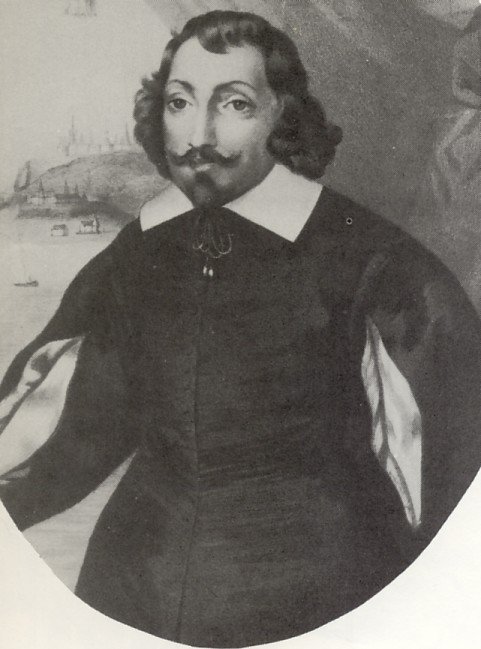

Samuel de Champlain |

|

|

|

Champlain disdained the fairy tales of fortune that had captivated Cartier. He sought something more wonderful than wealth: faith in the future of a new community in this new land. With his vision he saw the promise of endless possibilities. Without the energy and versatility of this dauntless seer, the French tongue would not have flourished on the banks of the St. Lawrence. For his love of and many labours in this new land, history has bestowed on him the proud title: Father of New France.

Champlain was said to personify all that was best in the French empire in North America. He was straight forward, unassuming, sympathetic and devout. He had the curiosity, perseverance, quiet wisdom and amazing fortitude of a born explorer and colonizer. Slow to wrath he was no hothead, but he was determined once his mind was made up. A moderate man who hated bloodshed, his forbearance and compromise combined in this slight, spare Frenchman to find new worlds and found new nations.

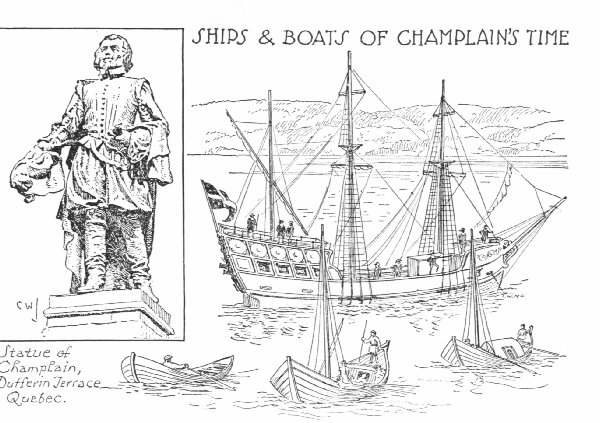

When he sailed up a river which he called the "riviere de Canada," he said it "shouted its uniqueness to adventurers." This great, North American river system pierced the the eastern seaboard and flowed into the heart of the continent. Providing mobility and access to the west with all its riches, the river became the heart and haven of life in the old province of Quebec. Vessels from a forgotten age - sloops, schooners, shallops, brigs, brigantines, canoes, bateaux and ferries - sailed over its surface. The country's economic and political life were fostered by its flow, for it opened up the heavily forested, well-watered land designed by nature to nuture the fur trade.

Champlain faced three main tasks: to get his men safely ashore and properly housed; to establish relationships with the Aboriginals; and to keep his financial backers satisfied. The beginnings of the colony were hard and humble as Champlain struggled with his principals in France to persuade them to validate his far-reaching vision of the new settlement. In Francis Parkman's fine phrase, Champlain was "the Aeneas of a destined people and in his ship lay the embryo life of Canada."

Champlain recorded this event in his journal. "I searched for a good place for our habitation but I could not find one more convenient or better situated than the point of Quebec." The site for a settlement was 'Place Royale,' one league from Mont Royal. "Having found this place to be the finest on this river, I at once had trees cut down and cleared away in order to make it level and ready for building. Water can be made to encircle the place very easily and a little island formed of it and a setttement made there such as one may wish." "Distrust," said Champlain, "is the mother of safety," The habitation stood in the shadow of the towering cliff at the very point where the St. Lawrence suddenly narrows before widening out once more. Kebek is the Algonquin word for 'strait' or 'narrow passage.'

|

|

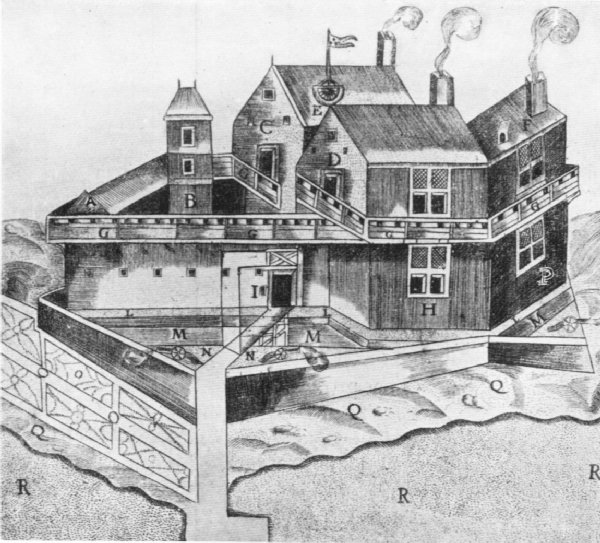

Champlain's Drawing of Habitation at Quebec |

|

|

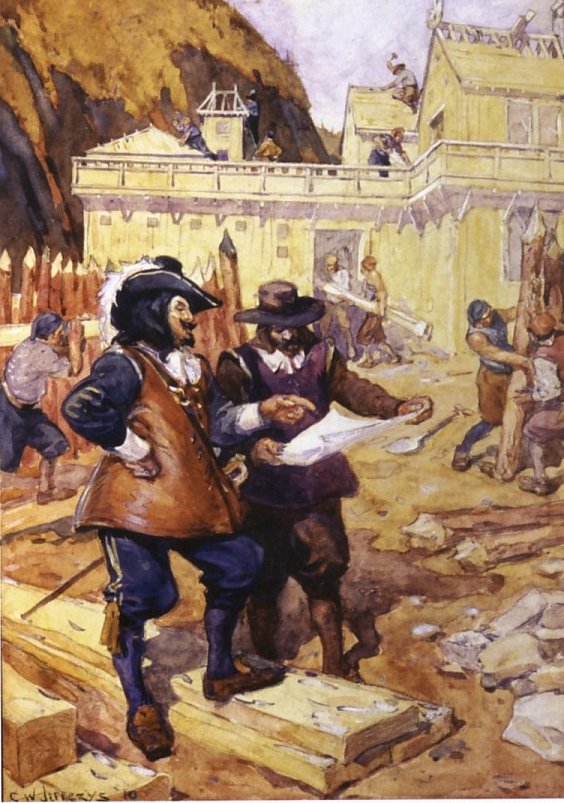

The Habitation Under Construction at Quebec |

Champlain was proud of the strength of this 'Habitation'. It had mounted cannon and a ditch 4.5 metres wide and 1.8 metres deep. It consisted of three clustered buildings, each 5.8 metres by 4 metres and two stories high. Around the the buildings there was a continuous wall above the ground floor forming an exterior gallery for defence. Outside the wall was a moat with drawbridge and a raised platform for cannon. Beyond that was an exterior palisade outside of which were the gardens. Atop the structure was a flagstaff flying the lilies of France. The history of New France can be said to have begun on that date for it marks the beginning of permanent settlement in the Lower Town of Quebec City, a collection of wooden buildings surrounded by a palisade of logs.

|

|

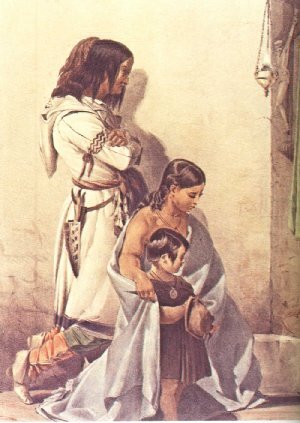

The Arrival of Madame Champlain |

|

|

Madame Champlain Teaching Indian Children |

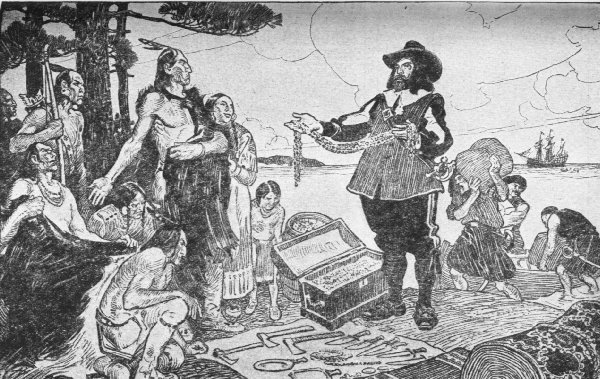

Money could be made in the fur trade. This trade financed exploration in early Canada. but eventually became detrimental to more lasting labours by enticing men away to the wild and wanton life of the wilderness. The passion for pelts resulted, some said, in "the class system, the subjugation of the Metis and many other ills." When fur trading for the year, the ships were ready to return to Frqnce with a fine cargo of pelts in the hold. It augured well for the future for the fur trade in the northern areas meant quick profits for the principals. Local Natives were friendly and accommodating, although danger lurked to the south where a strong military force was going to be needed. To keep the peace with the suppliers of fur, they would need to form an alliance.

|

|

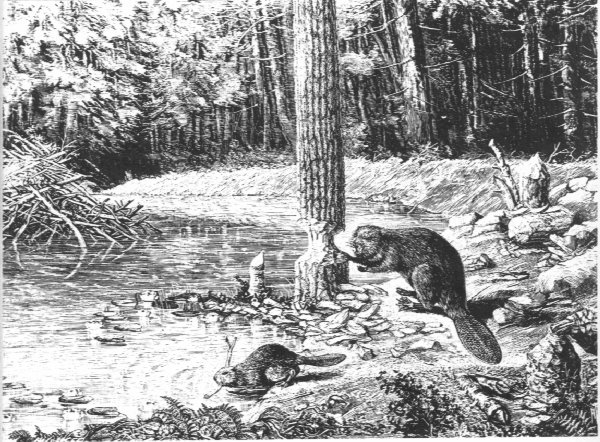

Castor canadensis - North American Beaver |

Some said the prolific little animal was the real founder of Canada, for the fur trade and the fast-flowing river determined Canada's history during the course of three centuries. This trade made and marred New France for it brought both great good and a profusion of evil. Without the beaver the country's settlement and development could have become simply another English colony. By 1600 fur-bearing animals in Europe had become almost extinct and late in the sixteenth century furs commanded a high price there. In North America adult beavers were big (averaging 50 pounds), plentiful (numbering 60 million) in the 1600s and relatively easy to catch. Beaver names and emblems were known to Natives long before the Europeans pursued the pelts. Onondagas had the Beaver clan and an Algonquin tribe was known as the People of the Beaver.

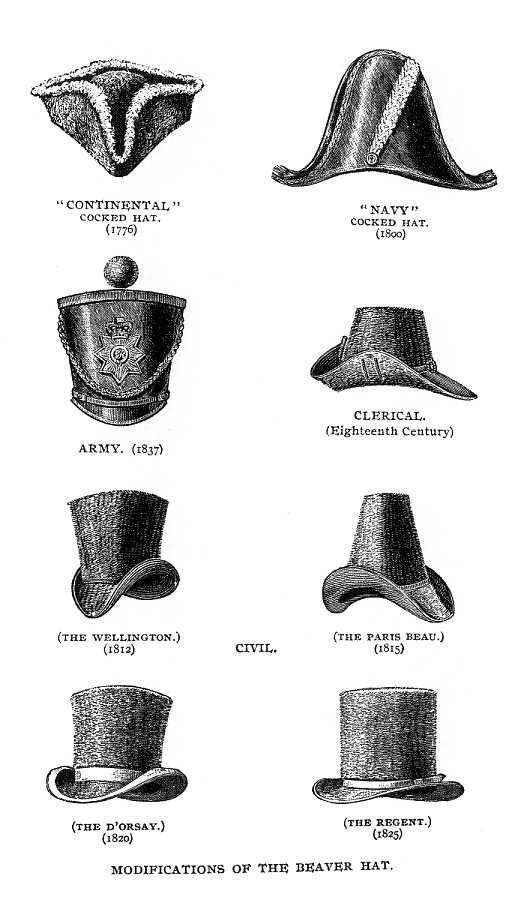

No fabric rivalled the warmth, wearability and beauty of furs and they were in great demand by both the men and the women of the upper classes. Important people wore them to display rank and wealth. Fur coats, muffs, wraps, gloves fur-trimmed garments and most importanly beaver hats all came into fashion. Hats off to the beaver. European men wanted felt hats and Natives wanted iron pots and tools and this fostered a brisk trade in pelts. Brimmed hats made of fur felt were highly prized and beaver fur made the best felt. By the late 1600s, nearly 100,000 beaver pelts were traded annually. A beaver hat cost 20-30 livres, almost one-third the monthly pay of a French army captain. Henry IV saw fur trade as a means of raising revenue and building an empire.

|

|

Beavers Before the Onslaught |

Hatters were wild about beaver. The most prized of the pelts was the pre-conditioned beaver hide that was known as castor gras d'hiver. Prime winter pelts were skinned by native women who scraped the inner sides, rubbed them with animal marrow and cut them into manageable rectangles that were sown together with moose sinews. Beaver robes were worn with the fur against the flesh and over many months the long 'guard' hairs in the fur that was already loosened by the initial scraping would drop off leaving only the short, woolly undercoat that made the finest kind of pelt. Felt was made by removing this cover coat from the pelt and rolling or pounding it flat. Then it was fastened together with shellac for shaping into a variety of stylish hats. Beaver pelts were preferred over other furs because of the microscopic barbs in the hair that hooked together so less shellac was required to created a fine "bever hatte."

|

|

Modifications of the Beaver Hat |

Trade between Natives and Europeans flourished for furs, particularly beaver. It was the most important animal fur in Canadian history, its long barbs at the tip of each hair in the soft underpelt making it ideal for felt. The felt-making technique transformed animal fur into a soft, supple, water-resistant material. The abundance of North American beaver stimulated European felt production and brought wide-brimmed hats into fashion.

|

|

Natives Trading With The French Early 17 Century |

Profit was prodigious for traders, but no one told the Natives. Some Natives believed it was they who were taking advantage of the Europeans. According to Father Le Jeune, "The Savages say the beaver is the animal well-beloved by the Europeans. I heard my Native host say one day jokingly, 'Missi picoutau amiscou. The Beaver does everything perfectly well: it makes kettles, hatchets, swords, knives, bread. In short it makes everything.' He was making sport of us Europeans." He remarked, "The English have no sense; they give us twenty knives like this for one Beaver skin."

While initially Natives did not perceive trade posed any danger to their independence, it did, in fact, revolutionize the Aboriginal way of life. They lost much of their former self-sufficiency and became more reliant on the Europeans. Fur trade depended on the labour of Native people. Each hunting family had traditionally used some thirty beavers annually for food and robes. After being worn for a year, the robe pelts shed their long, outer guard hairs exposing the short hairs required for the pelting process. The desire of the Natives for trade goods caused them to spend longer periods each year hunting inland for fur-bearing animals. Several hundred thousand pelts known as castor gras d'hiver were available annually in the St. Lawrence - Great Lakes regions at the end of the sixteenth century. The European demand for furs made them the second staple of the Canadian economy. It also led to the exploration of the Great Lakes and contributed to the war between France and Britain.

Beautiful fall passed into winter and cold winds, grey clouds and falling snow brought melancholy moods and thoughts of home. Winter also brought the scourge of scurvy, a deadly disease caused by deficiency of vitamin C. Characterized by spongy, bleeding gums, loose teeth, bleeding beneath the skin and extreme weakness, scurvy wreaked havoc on the habitation. Twenty-eight souls soon became thirteen.

Champlain recorded this description of scurvy's impact. "During the winter a certain malady attacked many of our people. It is called a land-sickness, otherwise scurvy. There was engendered in the mouths of those who had it large pieces of superfluous fungus flesh which caused a great putrefaction. And this increased to such and extent they could scarcely take anything except in very liquid form. Their teeth barely held in place and could be withdrawn with the fingers without causing pain. This superfluous flesh was cut away which caused them to lose much blood from the mouth. Afterwards they had great pains in the arms and legs which became swollen and very hard with spots like flea bites." The simple remedy for its ravages that was learned from the Natives by Jacques Cartier - spruce-needle tea - was not known to Champlain.

Despite this scourge, the little trading post became the centre of Quebec and the region an enduring heritage of the French. The mystical telegraph of the Natives carried the news through field and forest that the French had come to trade and stay. The new permanent residents soon became aware that warfare had followed them from Europe. Here in this new lovely land there was a long tradition of strife and among the fighting factions, one force was more to be feared than any other: the Iroquois. This fearsome foe was determined to dominate or destroy all rivals.

When Cartier had come to Quebec in 1535, the conditions along the St. Lawrence were vastly different from those that greeted Champlain. Cartier encountered Iroquoians, a mix of Huron-Iroquois who shared a common origin.

By the time Champlain arrived, the now-deadly Natives no longer lived in this area.The departure of the Iroquoians from the St. Lawrence Valley, the dominant event of the second half of the 16th century, occurred around 1580 about the same time French merchants discovered the vast potential value of Canadian furs. The river was the route used to some extent by the Mi'kmaq and the Maliseet, but above all by Montagnais, Algonquins and a few Hurons. While the Native peoples encountered by Cartier were fighters to be feared, they were mild-mannered men compared to the Aboriginals who now lived south of the St. Lawrence. They were ferocious warriors who inspired dread and terror in all who encountered of them.

What occurred between the time Cartier and Champlain came to Canada is not known for certain, but extensive research on the 'ethnohistory' of northeastern North America suggests that raids by the Iroquois living in present-day New York State may have led to the expulsion of the St. Lawrence Iroquoians. The landlocked New York Iroquois wanted trade goods, but found them difficult to obtain. In a frenzy brought on by envy and resentment, the Mohawks, the most easterly tribe of the Five Nations, raided and completely routed the Indians of the St. Lawrence who fled, many of whom joined the Hurons on Georgian Bay and Lake Huron. Champlain did not immediately come into contact with the fiercesome fignters living in palisaded villages among the Finger Lakes of northern New York, but word of their prowess in battle reached him from numerous sources. They called themselves the Ongue Honwe, "the men surpassing all others." and they did not take kindly to any who dared oppose them.

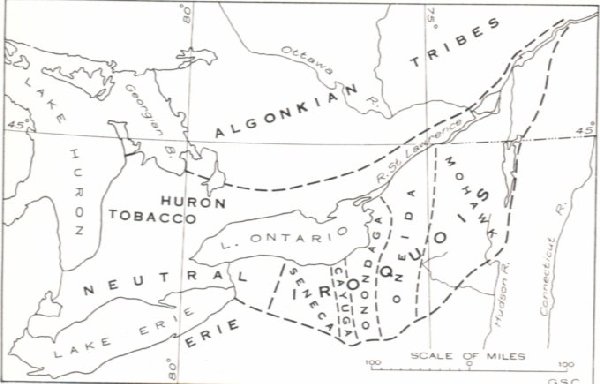

The areas south and west of Lake Simcoe were occupied by some 16,000 Hurons (Wyandots) allied in origin and language to the Iroquois. To the southwest lived allies and kindred of the Hurons, the Tobacco or Petun Nation. Their name came from the tobacco they cultivated and bartered widely with other tribes. Today, tobacco is an important crop still cultivated in their ancient lands.

Southeast of the Petuns and west of Lake Ontario on both sides of the Niagara gorge was the Neutral Confederacy, the peaceful Atiwandaronks "People who speak a slightly different tongue." They were named Neutrals by the French because they took no sides and refused to allow battles within their territory. They were friends alike of the Iroquois, the Algonquins and the Hurons.

Champlain described the Neutrals as a powerful people occupying "forty populous villages." He said the Neutrals were "the only nation living in total peace." They formed a confederacy or shifting alliance of tribes comprising five groups occupying from 28 to 40 villages lying south and east of Huronia. The confederation of tribes was common among Indians. Champlain said the Neutrals lived "West of the lake of Entouhonoronons (Lake Ontario) and north of Lake Erie and extended across the Niagara River." East of the Neutrals and occupying the basins of the Genese and Mohawk Rivers was the dread confederacy of the Five Nations.

|

|

Map of Iroquoian & Algonkin Nations |

The Hurons maintained a close friendship with the Algonquins to the north and east. While years before they had fought with their neighbours, the Tobacco people, by the time Champlain penetrated into southwestern Ontario, the Petuns had cemented close relations with the Hurons. The sole enemies of the Hurons were the Iroquois living south of the St. Lawrence River who warred with any neigbours refusing to enter their League. The Neutrals lived squarely in the path of the Iroquois and for years they and the Hurons had steadfastly ignored entreaties from the League of the Iroquois to fulfil their dream and join them in establishing the "Great Brotherhood."

Warfare between the various tribes took the form of raids and counter-raids during which no holds were barred. The Iroquois were warriors without peer in the region. At first they struck in small raiding parties and these sporadic ambushes and the retaliatory raids that followed seldom produced much change in tribal dominance. They served simply to provided warriors with their chief interst in life - proof of personal courage in combat. Fearful French colonists described the woodland warriors in this way. "They approach like foxes, fight like lions and disappear like birds."

Offensive weapons used included clubs, stone axes and bows and arrows. Tomahawks [****] did not appear prior to contact with Europeans. Some warriors used slat armour and wicker shields covered with rawhide to protect themselves from bone- and stone-pointed arrows. Wicker and rawhide proved no impediment to bullets and balls from muzzle-loading guns.

Neither side had really efficient military organizations. Discipline was non-existent since unwilling warriors could drop out of a conflict whenever they chose. This failure to fight incurred no other penalty than a little loss of public prestige. Defence like discipline was likewise loose. Some villages were protected by palisades, but most were not. Natives caught napping simply fled into the forest. Close contests between the two Confederacies might have continued indefinitely had not the Iroquois acquired more firearms and ammunition from the Dutch than the Hurons obtained from French fur traders along the lower St. Lawrence River.

|

|

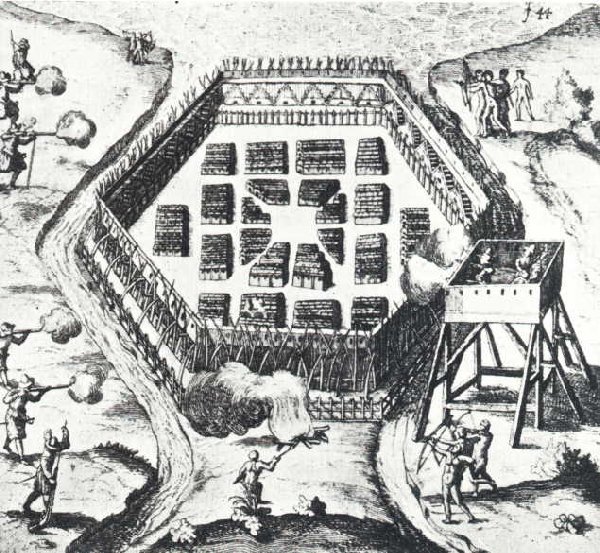

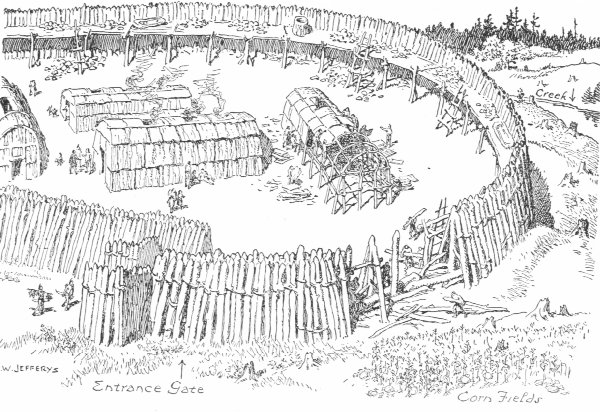

Hurons and French attacking a palisaded Onondaga village |

Because they flanked either ends of the confederacy, the Mohawk and the Seneca tribes encountered their various enemies first and because of the confederacy's loose organizational structure, they often acted independently of the other tribes. The Senecas were chiefly responsible for the destruction of the Huron, Tobacco and Neutral nations. The Mohawks took on the task of harassing the Algonquins, the Montagnais north of the St.Lawrence, the Abenaki and various other Algonkian tribes in the Maritime Provinces, New Hampshire and Maine. The three middle tribes, the Cayuga numbering 2,000, the Onondaga, 3,000 and the Oneida 1,000 contributed contingents for all major operations.

Because of the independent nature of each tribe, problems could arise when one tribe of the confederacy concluded a peace treaty with an opponent that was ignored or dismissed by the others. An example of this occurred in the 17th century when the French concluded a hard-won truce with the Mohawks only to find themselves dumbfounded and dismayed to be assailed by parties of the Onondagas and Senecas who did not recognize the Mohawk's moratorium on warfare with the whites.

The name Hotinnonsioni(Builders of Cabins) was given to the Iroquois. These people were the most comfortably lodged in long houses which contrasted with the small, circular wigwams of the Algonquian tribes which usually housed only one family. The early whites saw long houses that were "fifty or sixty yards long by twelve wide with a passage ten or twelve feet long down the middle for their fires." Each fire added twenty or twenty-five feet to the length of a cabin but rarely exceeded thirty or forty feet.

A typical town might have fifty of such dwellings. One was said to have two hundred. Each town was surrounded by a ditch, rampart and stockade so strong the English called them castles. Each rested on four posts which formed the base and support of the structure. Around the entire cicumference, that is, the two sides and the two gable ends, pickets were planted to secure pieces of elm bark which formed the walls and which were bound together with strips made from the interior coating or inner bark of white wood. The roof framing was made with poles bent to form a bow which were covered with pieces of bark that overlaped like slate. Inside the middle space was the fire whose smoke escaped through an opening made in the roof directly above, which served also to provide light since there were no windows. Movable pieces of bark were used to cover the hole during heavy rains.

In his quest to find a route to the East, Champlain needed help to hunt along the great rivers of the wilderness. To secure assistance and at the same time extend the trading area, he allied himself with the Natives of the St. Lawrence and the Ottawa and joined them in their war with the Iroquois. Champlain set off up river hoping to meet Indians from the west descending with their furs. His search was successful for some seventy miles above Quebec, he several hundred Hurons and Algonquins on their way south to solicit French aid in the fight with their ancient foe, the Iroquois.

Champlain eagerly greeted the Hurons, the great trading nation of North America that had applied their marvelous hunting skills to the fur trade. He agreed to join them in their conflict with the Iroquois and they trusted his word. Champlain's promise was based on a policy of conciliating neighbouring tribes from whom the French got furs. It was a commitment he had to honour for it was necessitated by the political realities of the St. Lawrence River. The first installment was a heavy levy for the alliance: the lengthy, costly conflict with the mighty Six Nations.

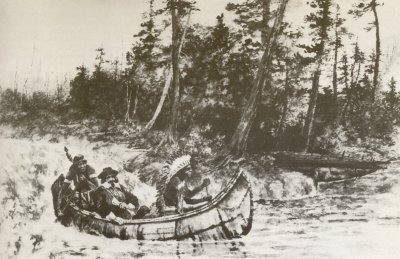

On the 28th of June Champlain set out to investigate and to invade the Iroquois. With a shallop capable of carrying twenty men, each bearing a short-barreled arquebus slung over his shoulder, Champlain entered the deep, broad, beautiful mouth of the "river of the Iroquois," the Richelieu. In the wake of the shallop were twenty-four canoes bearing warriors well daubed with war paint from the Montagnais, Algonquin and Huron confederacies. Champlain promised to walk the warpath with them in return for their promise "to take me to explore the Three Rivers as far as a place where there is such a large sea that they have never seen the end of it." Champlain was now about to fulfill his end of the bargain.

In the prow of the lead shallop, the intrepid, insatiably curious Champlain peered intently at the shoreline, enrapturd by the unspoiled, primitive landscape whose woods no whiteman had ever seen before. The intrigued mind of this perpetual adventurer was always eager to discover new mysteries. Captain, explorer, warrior, governor, anthropologist - Champlain distinguised himself in each of these roles. Versatility was what the new world required and it got that in spades with Champlain.

The lower stretches of the Richelieu River were easy going as it wound among "many pretty islands which are low, covered with very beautiful woods and meadows." Animals were abundant and little disturbed by their presence since no one had ever threatened them in this no-man's land. The Natives had assured Champlain they could sail up the river to the Lake of the Iroquois, but the roaring rapids at Chambly prevented their progress. Champlain disovered the handicap of the heavy shallop which could not be dragged through the rapids and was too big to portage among the large trees on shore.

By this time many of the men were becoming uneasy about the fate they were to face. Champlain noted this and wrote, "I was much troubled and it gave me especial dissatisfaction to go back without seeing a very large lake filled with handsome islands and with large tracts of fine land bordring on the lake where their enemies lived." "I determined to go on with my promise and to carry out my desire." Champlain called for volunteers to accompany him further and two stepped forward. Most apparently had real reservations about raiding the Iroquois, for in the words of Champlain, "their noses bled." He told them to return to their settlement at Quebec to which, "By God's grace, I too will return." This new development worried the warriors who expressed reluctance to proceed with the attack with only three Frenchmen.

The resolve and firmness of this man who had looked death in the face a hundred times convinced them that three would be enough. Champlain and two "who went cheerfully," set off with the Natives in their light, bark canoes. A review of their forces indicated that there were sixty Indians in twenty-four canoes. These marvelous vessels floated in a few inches of water and were easily carried by one man over the winding wilderness trails. Champlain admired the canoe's virtues and fostered its adoption by the French. The party included sixty Indians in twenty-four canoes and three Frenchmen bearing baggage, heavy arquebuses, powder, match, shot and armour.

Champlain described the scene in his journal.

In His Own Words

"I set out then from the rapid of the river of the Iroquois on the second of July. The Indians took their shields, bows, arrows, clubs, swords fixed to the ends of long sticks and their canoes and carried them about half a league by land to avoid the swiftness and force of the rapid. They made their way so fast that we soon lost sight of them. This displeased us. We followed their tracks but often went astray and would not have known where we were had we not caught sight of two Indians moving through the bush. We called out to them and they agreed to guide us." The others travelled quickly on ahead.

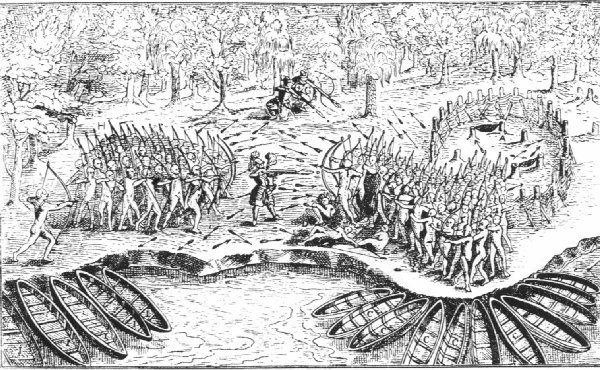

After rowing 120 kilometres they entered a large and lovely lake which Champlain named after himself. On the evening of July 29th, we sighted off the point what later became the site of Fort Ticonderoga a number of canoes that the our Indians immediately noted were heavy in the water. This indicated they were made of elm bark - the tree of choice of the Iroquois. We had we gone no more than an eighth of a league further before we heard the howls and shouts of both parties flinging insults at one another and scattered skirmishing whilst waiting for our arrival. As soon as our Indians saw us, they began to shout so loudly that one could hardly have heard thunder."

|

|

Champlain at Lake Champlain |

Contrary to the established practice of Indian warfare, the two parties approached each other openly and challenges to battle were hurled in jeering voices across the tranquil water. Two Iroquois canoes paddled out for a parley to learn from their enemies whether they wished to fight. They replied they had no other desire. The Iroquois were too well trained in forest fighting to risk conflict on the water and since it was dark and they could not distinguish one another, they vowed as soon as the sun rose they would attack. This was the etiquette of war: a parley and agreement on the hour of battle. Once this was completed the Iroquois returned to the shore from where they hurled taunts of their enemies' feebleness and foretold how they would be exterminated by the prowess of Iroquois warriors. Champlain's allies gave as good as they got, threatening ominously that the Iroquois were going to experience a power of arms such as they had never seen before.

The Iroquois then disappeared into the forest where they danced the night away to the flickering light of their fires, singing all the while in high, shrill voices their war chants, songs of insult and songs of celebration of their coming triumph. They had no doubts whatsoever that victory would be theirs. Champlain's companions, who spent the night in their lashed-together canoes, returned jeer for jeer. Champlain wondered at their resolve in the face of such fearsome odds for the Iroquois appeared to outnumber them four to one. Was their seeming bravado simply a case of whistling in the dark? It was hard to remain confident in the face of the awesome uproar coming from the Iroquois camp.

Morning found the Frenchmen donning breastplates, their highly polished metal reflecting the rays of the rising sun. Care was taken to ensure Champlain and his men came as a complete surprise. Each of the Frenchmen was in a separate canoe lying hidden on the bottom. Champlain and his companions waited, undoubtedly with some apprehension, the coming clash. The allies paddled to shore unhindered by the Iroquois, disembarked and formed in battle aray. With carbines loaded and sword and dagger dangling from their waists, Champlain and his companions advanced warily, their fingers steady as they awaited the onslaught.

Finally from out of the woods the warriors appeared, marching solemnly into battle with taunting laughter. Champlain described them as "strong and robust to look at coming slowly toward us with a dignity and assurance that pleased me very much." He was most impressed with his foes' physical magnificence. Tall, lithe, splendidly muscled, they were a superior looking enemy numbering about 200. Three chiefs, their heads topped with snowy plumes, strode ahead, their hysterical howling and fierce demeanour frightening to behold. The Natives told Champlain to be sure to shoot them.

Suddenly the Natives parted and Champlain in his casque with white plume and gleaming cuirass moved foreword slowly through the opening like some medieval machismo. Seeing a whiteman for the very first time, the Ongue Honwe fell silent, their fierce eyes filled with wonder and awe at this fascinating figure who was surely a white god. With no sign of haste, Champlain set up his arquebus on its stand and lit its slow fuse. He had loaded it with four balls. When he saw the Iroquois warriors move to attack, he prepared to fire. "I rested my musket against my cheek and aimed directly at one of the three chiefs." He pulled the trigger that connected fuse and breech powder. His eye and aim were excellent for the explosive charge felled all three of the chiefs, killing two of them instantly and the third after a brief period. When they saw all three chiefs drop, Champlain's allies raised such riotous outcry, he said "one could not have heard thunder."

|

|

Fire! |

The sudden explosion followed immediately by three stricken sachems jarred the senses of the Iroquois. They were astonished that two men had been so quickly been quelled even though protected with armour woven from cotton thread and wood so effective against arrows. But the musket blast released them from their transfixed spell and they realized they had to fight or die. They let fly a barrage of arrows at their enemies. At this critical moment, the two other Frenchmen exited from the forest and fired point-blank into the aroused Iroquois. The sudden appearance of two more gods with even greater thunder were too much terror for the Iroquois. The sight of all that flash, fire and smoke coupled with ear-splitting explosions caused the terrified fighters to turn and make for the woods. Their harried howling and panicked flight brought the French allies to life and with scalping knives and hatchets held high, they sprang forward in pursuit of their fleeing foes.

Champlain recorded the scene.

"I took aim with my arquebus and fired. They lost courage and took flight abandoning the field and their fort and fleeing into the depths of the forest whither I pursued them and laid low still more of them."

|

|

Champlain's Musket Blast |

Champlain won the battle but not the war for his first musket shot set off a savage feud between the French and the Iroquois confederacy that with little respite was to last a hundred years. It proved to be a costly cause to espouse, for the people of the Long House neither forgot nor forgave. Their hatred for the French never slackened nor was the spilling of blood ever sated.

Even after the Hurons had been exterminated and the Montagnais ceased to count as a fighting force, the feud festered. Inter-tribal warfare was not new, but European involvement changed what had once been periodic, local skirmishes with bows and arrows into wars of mutual extermination waged with weapons over vast territories. At firs the Iroquois were very wary of the white warriors with their death-dealing weapons, but when they acquired their own fire sticks, they took wide-ranging revenge.

Champlain was blamed for the blood that was lost for allying the French with the locals and provoking the Iroquois enmity that led to so much misery, but did he have any other option? His was a carefully considered policy for geography and trade made the choice for him. Colonization was possible only if the fur trade flourished sufficiently to ensure the financial backing of business associates in France. This in turn depended on the Montagnais and Algonquins whose long flotillas full of furs floated down the Ottawa to Hochelaga. In order to maintain this flow of fine furs, Champlain had to support his natural allies in their never-ending conflict with the Iroquois. If you wanted furs you had to fight. The Iroquois had no great regard for the English, but when the French and English fought as they frequently did, the Six Nations had no choice but to choose the English as allies.

|

|

Champlain's Travels |

When Champlain gave life to his little colony at Quebec, he was totally dependant for furs on the Montagnais and Algonquins trappers. The Iroquois and Hurons of the St. Lawrence Valley were not primarily trappers and so sought to establish themselves as middlemen between the Native tribes of the Shield and the French at Quebec or the Dutch at New Amsterdam at the mouth of the Hudson River. The Hurons were ideally located to act as middlemen because they occupied lands lying across the trade routes. The Iroquois sought to fill this role but they were not as strategically located since the supply of furs flowing to Quebec came by way of the Ottawa River route which led to the Huron country around Georgian Bay. The solution was simple. The Iroquois would take control of this vital highway and divert furs to their allies the Dutch on the Hudson River.

The French had no alternative but to protect their fur suppliers, so in July 1615 Champlain set out for the home of the Hurons to ally himself with them in their coming conflict with the Iroquois. The French ascended the Ottawa River, crossed Lake Nipissing and descended the French River to Georgian Bay. Throughout the journey of twelve days, Champlain, ever the eager onlooker, made copious notes of rapids, tributaries, islands, portages, flora, fauna and of Aboriginal life while in the Huron villages.

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

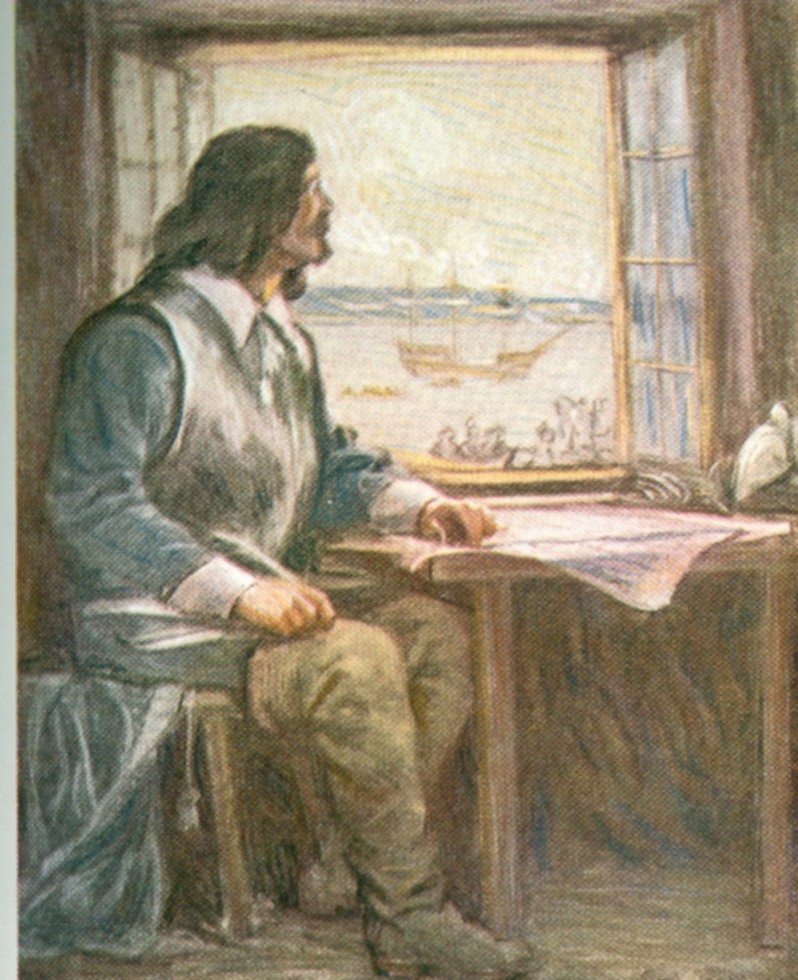

Champlain, the explorer, cartographer and colonizer, travelled thousands of miles on foot and canoe. |

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Champlain Taking An Observation on the Ottawa River with the Astrolabe he lost. |

|

|

Champlain on Georgian Bay 1615 |

Feasting and festivities celebrated the arrival of the French for the Hurons were greatly excited at the arrival of the impressive French force that would help them face and defeat the fierce Iroquois.

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Champlain & His Huron Allies Planning An Attack on the Iroquois in 1615 |

|

|

A Palisaded Iroquois Village |

The Iroquois village was surrounded by a stockade made of four rows of thick stakes thirty feet long, each lashed firmly to the next. Champlain proposed the construction of a tower from which they could fire down into the village. Predicatably, the Huron braves failed to follow the agreed upon plan and chaos ensued. According to Champlain, they "simply shouted war cries and fired arrows uselessly into the fort. I knew there was nothing I could say to them for they are not trained fighters and will not put up with discipline or punishment, but simply do whatever they feel like doing. I was shouting my head off to no purpose and getting nowhere with them."

During the three-hour free-for-all, two chiefs and about fifteen warriors were killed. This unexpected outcome, dampened the enthusiasm of the remaining Hurons, who began to murmur about retiring from the field. They had fully expected French firepower would panic and stampede the Iroquois, This failed to happen and despite heavy Iroquois losses, their fort remained untaken.

Before long the decison was made to withdraw. Because Champlain had been wounded in two places: in the thigh and in the knee, walking was difficult, so he was bound "as tightly as a child in swaddling clothes," strapped to the back of one of braves and borne away much to his extreme discomfort. "Never before have I suffered such agony. The pain in my knee was nothing to what I suffered from being bound. Before long it became more than I could endure and as soon as I could stand, I made my way on foot which I found much easier."

|

|

Huron Survivors Assisted by the French |

Champlain had intended to travel directly back to Quebec and requested an escort and a canoe. Four Natives volunteered to accompany him, but no canoe was available so with his usual forbearance he bowed to the inevitable and spent the winter with the Natives. During this lengthy sojourn, he studied their customs carefully and with the welcome arrival of spring, he finally left for home on May 20, 1616.

Not content to confine his labours and leadership soley to trade and war, Champlain devoted the remaining nineteen years he had left in his life to the development of Quebec. In 1615 he brought to Quebec four members of the religious order the Recollets, a branch of the Franciscan order, which came under the authority of Pope Paul V. Le Caron ministered among the Hurons; Dolbeau among the Montagnais and Jamay and Du Plessis remained at Quebec. With them the mission of New France was born. The power of the king paled before the power of the Church, whose heroic missionary efforts and devoted social services gave it great importance and prestige in the life of New France. It was the Church, not the monarchy nor the trading companies, that gave the colony the support it needed during its early, very trying times.

In 1625 another religious order, the Jesuits, came to New France. They established a religious monopoly comparable to the commercial monopoly of the Company of New France. They brought missionaries and money from France and before long soon crowded out the Recollets, who left and did not return to Quebec until 1670. Jesuit missionary work began among the Algonquins in 1625 and among the Hurons the following year. Their mission among the Iroquois dates from 1642. Their number included Brebeuf, Lalemant, Jogues and Le Moyne. They carried Christianity to the Indians and did praiseworthy work among their own countrymen and women in the cause of education and higher moral standards.

The government left colonizing in the hands of the traders, but because of their fixation on financial returns in furs and farming, they failed to fulfill to carry out heir responsibilities. Consequently, the growth of New France was so slow that Champlain had fears his little colony in Canada would be abandoned. While Quebec was founded in 1608, it remained largely a little fur-trading post with a few individuals residing in a rude garrison who could at any time be recalled to France.

A man named Louis Hebert, an apothecary, visited Acadia in 1604 and after returning to Paris in 1607 came back to Acadia and remained there until 1613. In the winter of 1616-17 Hebert renewed his acquaintance with Champlain who was then in Paris seeking support for his nine year old Canadian colony at Quebec. Hebert considered the tiny settlement safe and sailed with his family on the 11th of March, 1617. Described as the "first true colonist of Acadia," Hebert's skill as an apothecary and his small store of grain helped sustain the tiny group of settlers at Quebec. At Champlain's suggestion Hebert took a piece of land above the settlement and without waiting for formal title-deed, he undertook the herculean task in his spare time of clearing and cultivating it. Trees had to be felled and cut up, stumps burned and removed, stones gathered into piles and every foot of soil upturned with a spade. Sections of his land were sown with maize, peas, beans, other vegetables and part was set aside as an orchard. The remainder was used as pasture.

|

|

Louis Hebert |

Champlain visited Hebert's farm in 1618 and was pleased to discover cultivated land "filled with fine grain." For many years Hebert and Champlain were the only ones interested in cultivating the land. Hebert enjoyed the confidence of the Natives whom he found to be intelligent and good candidates for education. Hebert petitioned for a title to his land which he received on 4 Feb. 1623. A comfortable, stone, one-storey house was built around this time. It was the first dwelling erected on the plateau above the village. Hebert achieved his ambition to cultivate enough wild land to support him and his family in independence.

The meadows along the St. Charles provided pasture and the higher ground brought forth grain, vegetables and an apple orchard. All this had been accomplished by Hebert using only hand tools for ploughs pulled by oxen occurred after Hebert's death. During the winter of 1626, Hebert had a fatal fall on the ice and died on 15 Jan. 1627. His immediate descendants multiplied rapidly and helped populate Quebec which at his death was a struggling hamlet of sixty-five souls. Two-thirds of them were women and children and unable to till the fields. When Hebert and his family secured his land on the Plains of Abraham, they were joined by other wedded couples who decided to make their home in new world. The future and the fate of the colony could be heard in the familiar sound of happy cries of children born in Canada. And so they left a legacy, for from this pioneer Canadian there are many descendants in the province of Quebec today.

Champlain attempted to pressure the King and his Council to provide more support for the colony by arguing in 1618 that the English and the Flemings were so envious of the French colony's growing prosperity, they might very well attempt to seize upon the small settlement and "enjoy the fruits of their labours. To forestall such foreign takeover, Champlain urged action to save Canada and its many resources. "The forests are of marvellous height from which a number of vessels might be built which in turn could be laden with merchandise and other commodities such as cod, salmon, whale oils, hemp, silver, steel, iron, cloths, marble, jasper as well as abundant yields from the soil including cattle fed on the well-watered and fertile meadows."

Champlain promised "to undertake to discover the South Sea passage to China and to the East Indies by way of the river St. Lawrence which traverses lands of the said New France. This river issued from a lake about three hundred leagues in length from which lake flows another river that empties into the said South Sea" So said an account given Sieur de Champlain by a number of people. Likewise, he argued, "The traffic and trade in furs is not to be scorned. Not only marten, beaver, fox, lynx, and other skins, but also deer, moose and buffalo robes are commodities from which one can derive at present more than 400,000 livres."

Hope rose at the appearance of Richelieu att the court of Louis XIII. Cardinal Richelieu became the king's first minister and his inflexible velvet hand held everything in France. He deftly manipulated the king, the queen, the nobles, the army and the treasury. Gifted with imagination and "covetous of national greatness," Richelieu was eager to make France a great colonial power like Spain and England. He decided that New France should no longer languish and created the Company of One Hundred Associates, each of whom donated three thousand livres for working capital in exchange for which they received a monopoly on trade for fifteen years. Champlain was its first Lieutenant Governor. The company was expected during this period to bring out three hundred colonists a year up to 1643.

Champlain championed farming not fur trading as the enduring treasure of New France. The trading companies focussed on the sea for fish and the forest for fur-bearing animals as Nature's greater gift of wealth. Colonists were not needed for the first and would jeopardize the second since cleared land would lead to a loss of forest animals.

Colonization lagged because unlike Britain, France sent relatively few settlers to Canada and few came of their own accord. According to a familiar French saying, "Next to the Kingdom of Heaven, France is the most beautiful of all lands."

Champlain's description of New France as "a land of promise with the most beautiful rivers, the greatest lakes and the most fertile soil," fell on deaf ears. Tales of fierce winters and fiercer warriors were widely related in France and little effort was made to offset negative news and views with positive praise for the wonder and the wealth to be found in New France. |

|

Cardinal Richelieu |

|

|

Cardinal Richelieu |

In 1628 Richelieu's company sent out the first of four vessels bearing cargoes of provisions, munitions and a few settlers. Champlain eagerly awaited their arrival but he waited in vain for an English force led by a Scotsman named David Kirke captured the French ships in the Gulf of St. Lawrence. No sooner had word reached Champlain of this catastrope, than Kirke appeared before Quebec and in a note signed, "your affectionate servant," demanded Champlain's surrender. Champlain concealed his pressing need for supplies and in an equally courteous reply refused to yield. His bravado convinced Kirke that Quebec could best be captured by starvation so he sailed away to England leaving Champlain at Quebec to face the winter with few resources. When Kirke returned the following spring with a second summons to surrender, Champlain capitulated. Amid the beating of drums and the booming of cannons Champlain's little settlement sadly saw the English flag raised over its ramparts. With all courtesy Kirke returned most members of the captured colony to France.

|

|

Champlain Leaving Quebec A Prisoner on Kirke's Ship |

A distraught and careworn Champlain returned to France where he appealled to the Company and the king to re-acquire Canada. His petition restated his earlier arguments about the great value of the vast country "both for trade outside it and for the comforts of life inside it." In 1632 France and England signed a treaty that returned Quebec to France much to the joy of Champlain who had given almost life-long service to the colony.

On March 23rd, 1633 Champlain left Dieppe with a fleet of three vessels conveying men needed for the fur trade along with soldiers, craftsmen, labourers and some women and children. They reached Quebec on May 23rd and that same day they took possession of the post in a solemn military ceremony. A squadron of soldiers, pikes in hand and muskets at rest on their shoulders, went before him to the roll of martial drums. A quarter of a century of tireless effort had finally borne fruit in the realization of his dream - the settlement of New Fance.

Alfred, Lord Tennyson's oft-quoted last lines from Ulysses find a fit focus in Champlain as he led his small band back to the little settlement he sought so hard to found and foster.

Come, my friends,'Tis not too late to seek a newer world.

Push off, and sitting well in order smite

The sounding furrows; for my purpose holds

To sail beyond the sunset and the baths

Of all the western stars until I die.

Tho' much is taken, much abides; and tho'

We are not now that strength which in old days

Moved earth and heaven; that which we are, we are;

One equal temper of heroic hearts,

Made weak by time and fate, but strong in will

To strive, to seek, to find and not to yield.

Now an old man Champlain, wished to end his days on duty in New France as the king's lieutenant of the land he loved. As the last days of July drew to a close 150 canoes reached Quebec, paddled by five hundred Hurons and laden with the richest skins. Sixty of their leaders held a council and welcomed Champlain back with genuine emotion.. The rhetorical gifts of the red man were among his many endowments and their eloquence was lavished on a leader they loved and respected.

Champlain resumed his work of restoring relations with the Hurons and Algonquins since everything was dependent on profits from the fur trade. In 1634 he built a fort to check the English seaman seeking a share of the fur trade and established a new settlement at what became Trois Rivieres where he constructed a battery of cannon. Well aware of the little settlement's inability to defend itself, Champlain appealled to Richelieu and proposed that 120 men armed with light weapons be sent to Canada. He believed that their strength combined with that of two thousand Natives would be sufficient to crush the enemy. Richelieu failed to reply to this passionate appeal which proved to be Champlain's last. Despite his best efforts the colony continued its meagre, hand-to-mouth fashion and he never did see it grow and prosper.In his fortress of St. Louis the great man of North America lay dying. Paralysis struck him in October and Christmas Day 1635 saw the end of his arduous, noble and notable career. Thee founder of New France died at Quebec at the age of sixty-eight. He was given, said Father Le Jeune, who delivered the funeral oration, "a very honourable burial, the procession being formed of the people, the soldiers, the captains and the churchmen. Those whom he has left behind have reason to be well satisfied with him." His body was buried in the town he founded in a neighbourhood chapel named Chapel of Champlain. They buried him never suspecting the size and significance of the nation he had founded. Five years later the chapel was destroyed by fire. No one knows where the dust of the founder lies buried.

Champlain, the heart and soul of New France, is the most outstanding figure on the threshold of our national history. He founded Quebec and for twenty-seven years was a voice crying in the wilderness for sustenance for the settlement. Champlain, the sailor, made twenty voyages to and from France. His work as a navigator led him to "remote regions, the hazards of which made life the more delightful." On the title page of his last book published in 1632, he proudly described himself as a sea-captain whose greatest achievements were his maps. He was first to chart the Atlantic coast of New England and Canada with amazing accuracy. He left a Canada whose boundaries had been pushed far back into the unknown. Much of the Great Lakes system had been explored by himself, his young men and the coureur de bois and missionaries working both under his encouragement and after his death.

As an explorer Champlain was eager at any cost or discomfort to open the unknown and was at home in the rough life of the fleet or the forest. He crossed the ocean under the king's flag and found new rivers and new routes through the "trackless wilderness." He could sit with a king or share a council fire with Natives who admired his dignity, his wisdom, his sympathetic insight and his high character. He was a colonizer who planted the most important company of Frenchmen in North America. They became pioneers of discovery and trade that spanned a continent. They cleared forests and despite hard life on the edge of the wilderness they clung to the soil and endured. A many-sided leader Champlain was also a fervent Christian preoccupied with spreading the faith among the Natives. He once said the salvation of a single soul was of more value than the conquest of an empire. Champlain was quite simply one of the finest characters of his nation combining energy, practicality, loneliness, tough nerves and inarticulate love of the Canadian earth that would make Canada

|

|

Champlain contemplating the future of what became Canada |

|

|

Monument to Samuel de Champlain by Hamilton MacCarthy at Nepean Point near Parliament Hill, Ottawa |

|

|

Louis XIV |

|

|

Musketeer of the Carignan-Salieres |

On April 19, 1665 the first four companies of the Carignan-Salieres regiment set out for New France. Their mission: "to carry the war to their doors and to exterminate the Iroquois utterly." The best the French could do was burn their castles and their cornfields, but these limited onslaughts lessened for a number of years, Iroquois attacks on the French settlements. However, the festering feud blocked French extension southward and staunchly allied the Iroquois to the English, an alliance that lasted down to the capture of Quebec by General James Wolfe in 1759.

Because the St. Lawrence was the artery of travel in early Canada, almost all settlement was along its banks. Officials and most seigneurs favoured the establishment of villages on the banks of a river. The habitants preferred isolated farmhouses on their own river lots. Behind official preference for overseeing settlements in villages was the concept of control. Habitants on the other hand countered this concept with a more loosely structured independent way of life made possible by remoter residences. With the forest at every back door and the river at every front door, unobtrusive movement along the St. Lawrence was easy and virtually impossible for government officials, seigneurs or the church to control.

In the century and a half Quebec was a French colony, only about 10 thousand immigrants came to Canada. Of those who emigrated from France, almost 4000 were engages - indentured servants who were committed to several years of service to those who engaged them. Approximately 3500 were soldiers released from military service. Towards the end of the French regime, 1000 prisoners - salt smugglers for the most part - were sent to Canada and in the late 1660s almost as many women were shipped out to become wives. At most 500 immigrants came on their own and all but a handful of these were French. They came principally from the north and west in the immediate hinterland of La Rochelle, the principal port of embarkation for Canada. Most came because they were sent since immigration grew out of official policy decisions rather than individual excitement over the lure of the new land whose reputation was not good. Knowledge of the cold climate and hot native inhabitants was widespread and few wished to leave family and the land they knew for an uncertain future in a faraway place.

[*] The National Post, March 22, 2008Champlain Gets No Respect

Few French citizens of his birthplace have ever heard of him and certainly do not consider him the most important native of Brouage, this historic fortified city that draws some 400,000 visitors a year.To add injury to insult, a bookstore owner in Brouage said she had no books about Champlain and had never heard of the man. "Is he a traveller? she asked." Well you might say that!!

The title of the town's most important historical figure goes to Marie Mancini, King Louis XIV's first true love. The Sun King was forced to marry Maria Theresa of Spain in 1660 for political reasons, but he walked up the stone steps to the ramparts surrounding Brouage and wept so powerfully over the forced termination of their romance that a river of tears flowed down the steps. [**]July 23, 1908

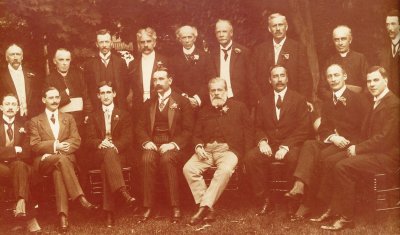

"Tricentennial of Quebec 1906

Standing in front of the Champlain Monument, the Prince of Wales officially inaugurated the Tricentennial of the founding of Québec City. The Governor General of Canada, Lord Grey, played a key role in the organization of the event, associating the memory of the battle of the Plains of Abraham and the celebration of the British Empire. The festivities, which took place from July 19 to 31, were marked by outdoor historical shows, parades, banquets, balls and fireworks..

|

|

Tricentennial of Quebec Banquet |

(Back Row) 4th from left: Sir Robert Borden: Prime Minister of Canada 1911-1920;

5th from left: Sir Wilfred Laurier, Prime Minister of Canada 1896-1911) (Sitting) 2nd from left: Arthur C. Murray, from General Murray's family;

3rd from left: Count Bertramd D. Montcalm

4th from left: George Wolfe

5th from left: Marquis de Levis;

7th from left: Captain D. Carleton.

[***] The National Post March 15, 2008

Tourouvre, France

Two-thirds of French Canadians can trace their roots to 283 early settlers

[****] Jacques Cartier used the word tomahawk for hatchet, but did not state that it was used in combat. A century later another European speaks of the Mohawks using, "weapons of war such as bows and arrows, stone axes and clap hammers."

The overhanging, wall-mounted turret projecting from the walls of medieval fortifications from the early 14th century to the 16th century is called a bartizan or guerite.

Items marked with [#] have been forwarded by Jean-François Demange, who lives in Navarre and frequently visits the homeland of Champlain. Jean-Francois says that Brouage used to be on the ocean front, but has subsequently become inland. He commented that this may be nature's way of punishing France for abandoning her sons in Canada.

The sea far off withdrew, as the sea at the bottom of time, and the unknown fortress does not live more than in the breath of winds.

But and she can be reborn, the city of the lost dreams, her heavy past stopped being a harvest of disappointed hopes.

Most fascinating, concerning Brouage, is the fact that if France abandoned his sons in New France, as to punish her, Ocean abandoned Brouage.

Copyright © 2013 Website Administrator