foreword | Historical Narratives | Resources | Links | Contact

LAND ALLOTMENT & REGISTRY OFFICES

History rests on pieces of evidence, written records and other works created in the past and surviving into the present.

"The Lord bringeth thee into a good land,"says the Bible and it did not take the Loyalists long to discover that much of it was located in Upper Canada. This fact was confirmed by Samuel Holland, Surveyor General.

|

|

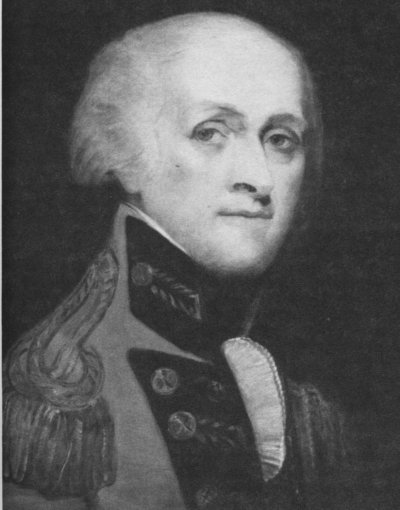

Samuel Holland |

Governor General Sir Frederick Haldimand, the aloof Swiss professional soldier, believed that the Western country should be reserved for the Aboriginals whose loyalty to Britain had been sorely tried by the terms of the peace treaty with the United States which consigned their traditional hunting grounds to the new republic. However, when Haldimand learned that the Natives of the area would not consider the Loyalists unwelcome invaders, he directed Holland on May 26th, 1783 to "proceed to Cataraqui [Kingston] where you will examine into the situation." Haldimand subsequently settled a number of Loyalist groups along the upper St. Lawrence where he granted them land and basic supplies. He instructed Holland to send his assistants to the Niagara country to assess its suitability for settlement.

|

|

Frederick Haldimand |

Holland's subsequent reports about the quality of the land greatly impressed Haldimand. Although some of it was "broken land" by which he meant rocky because of the Precambrian Shield which stretched down across the St. Lawrence River, most of it was so fair that

In His Own Words

"I think the Loyalists may be the happiest people in America by settling this country."

These positive reports led to plans for the launching of pioneer land surveys of the upper country. British practice was to forbid private purchases of land from the Aboriginals. Instead the government negotiated with the Natives leading to formal treaties with Aboriginals who regarded themselves as allies, not subjects of the British king. The government alone gave legal title to Aboriginal lands. This policy was the basis of peaceful relations between England and Canada with the Native nations, unlike nearby American states where American troops clashed repeatedly with the tribes of the Ohio valley who were forced to fight American interlopers to preserve their rapidly disappearing land legacy. Upper Canada never had a fiery Native frontier.

|

Acting on behalf of the Crown in October, 1783 William Redford Crawford of the Royal Regiment of New York purchased from the Mississaugas [People of the large river mouth] who were located on Carleton Island, land for settlement which eventually became the counties of Frontenac, Prince Edward, Lennox and Addington, Hastings, Glengarry, Stormont, Dundas and Leeds. At Niagara on May 22nd, 1784 Major John Butler completed negotiations with the Mississaugas for the purchase of an extensive "tract of country" for settlement situated between Lakes Ontario, Erie and Huron. For the sum of 1180 pounds, 7 shillings and 4 pence the said "Wabakanyne, Sachems, War Chiefs and Principal Women in band will and truly did grant bargain, sell, alien, release and confirm unto His Majesty all that tract or parcel of land lying between the Lakes Ontario and Erie." The purchase of this land by Indian treaty made possible the western spread of the settlement of Niagara. Negotiations for land did not always conclude cordially. In this instance there appeared to be some dispute over the accuracy of the boundary of this purchase.

|

In a letter written by John Graves Simcoe in March of 1792, Simcoe indicated there were "doubts relative to the Boundary" of this land purchase from the "Messessaga Indians" and he requested that Samuel Holland determine whether "a North West Course drawn from the Waghquatata Lake does or does not strike the River La Tranche or New River."

Presents promised to the Native peoples for their land did not always reach them. In September 1793 Simcoe reported to his superior that "the Messissagua Indians, who are the original proprietors of the land which as been sold to the Government, make great complaints of not having received the presents which they stipulated when they sold the lands. Colonel Butler upon my enquiry told me this originated from a mistake of Sir John Johnson's who had given the presents to the wrong persons."

|

In January, 1794 Lord Dorchester informed Simcoe that a plan for another land purchase had been found in the Surveyor General's Office which contained a blank deed "with the names or totems of three Chiefs of the Mississaga Nation" attached thereto. The totem mark of the Mississaga was an eagle, however, since the deed was blank it had no validity and Dorchester said it would be necessary for the British government "to purchase it anew." [* See below]

In November 1795 on behalf of the British government John Butler negotiated with the principal "Chiefs of the Missasaga Nation" for the purchase of "the Spot of Land delineated on the Sketch" This 'spot' of land was six miles deep from each side of the Grand River beginning at Lake Erie and extending to the head of the river. This land was to replace land lost by the British allies, the Six Nations Indians, in what became New York State following the American Revolution. Butler said the Missasagas consented to part with it "without any hesitation" for which they received "1180 pounds paid to seal the bargain." It was reported that the "Missasaga Nation of Indians was an unsettled people numbering about six hundred men, women and children."

|

|

Shaded Section on Left: Land of the Six Nations |

Large scale surveying of the land purchases was begun by the Deputy Surveyor General, John Collins, who was directed by Haldimand to proceed "to Cataraqui in order to survey and mark out the settlement at that place for the refugee Loyalists" for whom farm lots were urgently needed. "Excessive bad weather" had waterlogged the countryside and delayed the commencement of work until late October, 1783.

What was the surveyor's task? "It was to measure the natural features of the earth and its waters, to scan the heavens, to locate and fix the boundaries of areas into which man has decided to divide the planet and to determine precise dimensions, directions and relative positions. His work meets the urgent need of man to see his locality, his nation and the world as a whole and in relation, one to the other; to orient himself and his interests within the earthly and heavenly environment."

Townships were laid out and divided into concessions which were divided into lots. To ensure fairness in the distribution of the land Haldimand directed that the lots be awarded "impartially by drawing for them." He insisted this was to apply equally to the officers as well the lesser ranks a decision which was not popular with the former.

The physical and man-made conditions under which surveyors laboured were harsh and often difficult. In addition to working in"excessive bad weather" while being eaten alive by "insects in such multitudes," Lieutenant Governor Simcoe established tough working terms for them. In 1792 Simcoe directed that one quarter of a dollar a day be allowed to the surveyor "to find your own ration." For a "coasting survey" any number of men up to ten could be employed. For an "inland survey" not more than 12 could be employed. The allowance for axemen was 1/6 of a shilling a day; for chainbearers 2 ½ shillings a day. For the quarter dollar a day he received the deputy surveyor was obliged to provide for each person in his party: 1 ½ pounds of flour, 12 ounces of pork and ½ pint of pease (peas). If he was "furnished with a Battoe, (bateau) axes, tomahawks, camp kettles, oilcloths, Tents and Bags from the King's stores, you will be allowed only 10 pence rations for your party."

|

The practice at the time was for the surveyor to set up his circumferentor on a level stump or a flat rock and take a sight along the intended township baseline. Axemen cut away obstructing trees. One chainman carried and opened up the remaining 99 links of the chain to a point determined to be precisely correct. The surveyor then signalling the picketman to drive in a stake at that point. At the termination of every fourth lot a span of one chain was provided for a future side-road. If he came to a creek or swamp the surveyor recorded that feature in his field book. He also entered details regarding the quality of the soil, the number of rock outcroppings and the types of timber.

|

Land grants were sought by Loyalists and other settlers as a natural right and by lobbying and intense labour they often acquired large holdings. Land was allotted in a variety of ways and over time confusion resulted regarding who owned what and where it was located. In order to ensure that property and its rightful owners were dutifully documented, registry offices were established in the various counties. The bicentennial of their establishment was 1997.Settlement in the province began in 1784 when land was granted by the "bounty of His Majesty" to Loyalists and disbanded troops who had joined the Royal Standard during the American War. Initially land grants were made by commanding officers of the various posts under authority of the Commander in Chief.

Surveyors normally surveyed the land into 100-acre parcels but exchanges of lots based on personal preferences permitted the acquisition of larger holdings in a particular location. Mining rights on the land were excluded for titles were granted solely for the purpose of agriculture with the Crown retained mining rights on all properties. To be granted a lot one had to be a professing Christian, physically capable of clearing, cultivating and improving the property and be able to provide proof of having obeyed laws and led a life of inoffensive manners in one's former country.

|

Candidates also had to subscribe to the Oath of Allegiance and the following Declaration: "I, John Doe, do promise and declare that I will maintain and defend to the utmost of my power the authority of the King in his Parliament, as the Supreme Legislature of this Province." Settlers who refused or neglected to comply with the declaration were "turned off" their property forthwith.

|

One petitioner named David Palmer submitted the following petition to Lieutenant-Governor John Graves Simcoe on July 5th, 1795.

In His Own Words "To His Excellency John Graves Simcoe, Esquire, Governor and Commander in Chief in and over His Majesty's Province of Upper Canada.

The Petition of David Palmer

Humbly sheweth:

"That your Petitioner was an Inhabitant of Sussex County, State of New Jersey, and for many Years followed the business of a Miller by which he supported himself and Family in a Reputable way and was situated in a part of the said state where the Refugees and other Loyalists that had fled to the British standard. Resorted in a Private manner by means of which he had it in his power to Give them succour, which he did in the best manner he could and also gave great assistance in getting their Recruits to the Army, whereby he became suspected by the then Ruling Power and suffer'd much in his property by the Severe and Inhuman Laws passed in the said State against Loyalists, whereby he became little better that a Bankrupt and that in the year 1788 he came to this Province with his Wife and Children, several of whom are now become Inhabitants. Therefore, your petitioner prays that your Excellency will Grant him such an allotment of Land as you in your wisdom may think he merits and your Petitioner as in duty bound will ever pray.

40 Mile Creek, July 5th, 1795"

Palmer received a grant of land located in what is now the Grimby area shortly after his arrival in Upper Canada. The above petition was for additional land.

Land was distributed by lot with each pioneer receiving a certificate signed by the Governor and counter-signed by the Surveyor General or his deputy. It declared that John/Jane Doe, entitled by His Majesty's grace to a quantity of land had drawn Lot Number 'x' in a certain concession of a certain township. Having settled thereon and improved his location the grantee at the expiration of 12 months was supposed to receive a Deed of Concession which permitted the owner to alienate (transfer) or devise (bequeath) the property.

Land Boards were introduced in the various districts in 1789 to ensure orderly and loyal settlement. The five-year period during which they existed extended over the important pioneer growth period when townships along the upper St. Lawrence, around the Bay of Quinte, along the north shore of Lake Ontario and the west bank of the Niagara River were settled.

|

|

Dark Sections Indicate Areas of Early Settlement |

An important part of the Land Board's function was to control the extensive growth of land speculation which made its appearance at a very early date. Much of the speculation resulted from individuals from the United States who applied for land to sell, not to settle. Newly granted land not actually settled within a year was forfeited, and land could be transferred only with Board approval. Persons not intending to become active settlers were refused applications and entries of ownership often had to be cancelled for non-settlement. Boards also confirmed property locations previously made and granted lands by certificate.

Simcoe became impatient with the pace Land Boards set for populating the province and successfully secured their abolition on November 6, 1794. Magistrates of the different districts handled allotments of land up to two hundred acres while the Executive Council and Simcoe himself awarded larger grants of land including whole townships. Once the Land Boards had been eliminated there was no mechanism to screen applicants for land. Regulations to check speculation did not work and they contributed to confusion and delay in issuing legal title. The system did, however, satisfy Simcoe's desire to make Upper Canada a place where settlers found land easy to acquire.

Despite attempts to document ownership the sole proof of title was often the fading script on the yellowing scrap of paper originally issued. For ten years after the first land allotments were made scarcely a single grant had been ratified. By then many settlers were reluctant to exchange their jealously guarded yellowing piece of paper for an official document.

During its fourth session in August, 1795 Upper Canada's first parliament ratified the Registry Bill. It was considered so important by the Members and those they represented that it was passed quickly with only a minor amendment made to its preamble. This first of our Registry Acts established a registry office for each county and paved the way for the general issue of patents by providing for the registration of all deeds, mortgages, wills and transfers.

In order that "deeds to perfect titles" could be granted it was proclaimed on August 21st, 1795 that lawful land claimants must make known their claims to the attorney general within six months by the production of tickets, certificates or "such other testimonials" so that grants could be issued under the Great Seal of the province. Land owners were warned that failure to submit such documentation could result in the lands being "deemed vacant and granted to other applicants."

The existence of private property made survey markers or monuments critically important and "cursed be he that removeth his neighbour's landmark." Upper Canadians did not take kindly to willful interference with their boundary markers and few places in the world had penalties as severe for removing or damaging them. During the first session of parliament held in York in 1798, the Legislature enacted a statute which stated: "If any person or persons shall knowingly and willfully pull down, alter, deface or remove any such monument as aforesaid he, she, or they shall be adjudged guilty of felony and shall suffer death without benefit of clergy,"The latter phrase signified punishment of utmost severity. Over the years the sentence was softened and became a misdemeanor in 1849. Today the maximum sentence for disturbing a boundary monument is imprisonment for five years.

Toronto Built on Bargain Land [*]

"Pittance paid for 100,000 hectares. At the very least it could be described as the mother of all bargains. At the most a case of grand theft land. For 10 shillings - then roughly the daily earnings of a low-ranking foot soldier in the British army - the government of the day bought up the land that is now Toronto. Now, nearly 200 years after the 1805 sale that saw more than 100,000 hectares of land change hands, the government of today and the Mississaugas of the New Credit First Nation are poised to hammer out a better deal - one that has the potential to be one of the largest land claim compensation settlements of its kind."On Tuesday representatives of the federal government and the Mississaugas will hold a joint press conference in Toronto to bring the public up to speed on the history of the so-called "Toronto Purchase" land claim and where it is headed. The two sides, says Chief Dan LaForme, are about to begin negotiations in earnest. In 1805, the last time they sat down together to seriously negotiate, a revised deal was reached - one that attempted to remedy a previous flawed deal made in 1787. The earlier treaty resulted from a meeting between one of the King's men and the Mississaugas at the head of the Bay of Quinte and purportedly ended with the Mississaugas surrendering all lands north of Lake Ontario. The deed, however, was unsigned and that was a problem.

"Years later, in 1805 a government representative approached the chief of the Mississaugas (those involved in the first deal were dead) with a fresh proposal. This time the land was surrendered for 10 shillings. The surrendered land stretches over 20 kilometres from Etobicoke Creek in the west to Ashbridge's Bay in the east and extends inland more than 40 kilometres. The Toronto Islands were not part of the first deal. Somehow they ended up on the second surrender deal according to the Indian Claims Commission's Web site and the First Nation never accepted the boundaries as spelled out in the 1805 treaty. The band says the islands were not part of either deal and both are being disputed.

"In all the land in question covers 100,312 hectares. The Mississaugas say the land was never properly surrendered. The Mississaugas' claim is one of many similar ongoing claims across the country. Many have ended up in court tangled in lawsuits. That has not happened in this case. And that is how Chief LaForme would like to keep it. "The government of Canada has been willing to sit down and proceed with negotiations, so that tells us that they're willing to come to some kind of agreement with us, rather than taking the court route." LaForme said he has no idea how much a settlement in this case might be worth to the 1,500 Mississaugas who live both on and off the reserve land. The Mississaugas settled a claim on an 81-hectare parcel of land in 1997 for $12 million."

[*] From the Toronto Star, June 11, 2003]Copyright © 2013 Website Administrator