foreword | Historical Narratives | Resources | Links | Contact

JOHN GRAVES SIMCOE

History is a form of autobiography, an essay in self-knowledge.

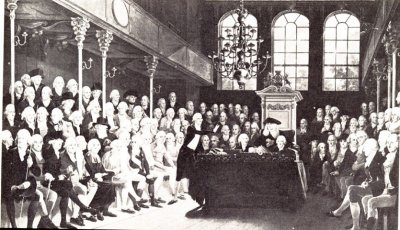

The Constitutional Act of 1791 resulted in the division of Quebec into two provinces: Upper and Lower Canada. John Graves Simcoe, a member of the House of Commons that approved the act, envisaged a fine settlement in Upper Canada populated by Loyalists, many of whom he had led as members of the Queen's Rangers during the revolution.

|

|

Queen's Rangers Badge |

In order to create this wonder in the wilderness, Simcoe applied for and was appointed to the position of lieutenant-governor of the colony in the wilds of the new world, a commission he compared to a "species of banishment."

|

|

House of Commons Debates 1792 |

While John Graves Simcoe occupies a modest and very minor place in English history, he holds a distinctive honour in the history of our province. He was Upper Canada's first lieutenant-governor and the most effective of all British officials dispatched from London to preside over a pioneer society. Simcoe was denied the opportunity to serve his country in a military capacity and became instead a stubborn, strong-willed autocrat presiding over a forested fiefdom deep in the heart of North America. The appointment which lasted 4.5 years and was to be but an incident in a life he wanted to devote to soldiering, however, this somewhat tragic figure was denied the opportunity to practise his preferred profession.

Simcoe began his military career with high promise and quickly achieved uncommon success. He purchased his captaincy but his subsequent promotions were made by merit. He became a major at the age of 25 when in 1777 he assumed command of the Queen's Rangers and was made a lieutenant colonel the following year. While subsequently he received promotions to major general in 1794 and lieutenant general in 1798, he never again assumed an operational command. He was, however, during the invasion scare of 1801, entrusted with the protection of the most endangered sectors of the English south coast - Plymouth and and County Devon. The war office must have thought highly of his competence because in 1806 at the age of 54 he was appointed Commander-in-chief, India. Here at last was the challenge he had chased. Fame, it seemed, had finally come.

Before Simcoe could take up this task, he was sent on a mission to the court of Lisbon to report on steps needed to protect Great Britain's oldest ally from the threat of an imminent French invasion. En route Simcoe fell ill and returned home to die at Torbay on Oct. 25, 1806. Simcoe died just plain John Graves Simcoe, one of the few British lieutenant generals of that time who was not knighted. Such are the fortuitous turns of events in history. His reputation was high enough with the war office, but not with the fountainheads of honours - the King and Prince Regent.

In a letter to Joseph Brant in 1791, the Duke of Northumberland called Simoce "brave, humane, sensible and honest." These qualities shine forth from the military journal Simcoe kept. About Simcoe's performance as lietuenant governor of Upper Canada there may be divided opinions, but as a military man there can be no doubt at all. His talents were surely wasted during a very tense and trying period of British history.

Despite criticism from some quarters, Simcoe dwarfed his successors by bringing to the task of creating a new colony, vigor, vision and limitless enthusiasm. The latter characteristic was revealed by his oft-repeated assertion that "A thousand details crowd upon my mind." These countless concepts and limitless proposals resulted in zealous activities, lengthy - called 'tiresome' by their recipients - dispatches to London and numerous frustating disappointments. His voluminous correspondence with the Colonial Office represented a continual debate between metropolitan officials and a local zealot.

|

|

John Graves Simcoe |

Simcoe might well have been nicknamed the Resilient Governor because despite disappointment after disappointment, his fertile imagination continued to produce numerous plans and projects that tumbled over each other in his restless and resourceful brain. He tendency to be driven by his dreams resulted in him sending his superiors in London diverse dispatches that were comparable to exhortations. Simcoe's official communications, a curious blend of passionate petitions and trite platitudes, resulted from his fiercely fawning determination to act on the slightest hint his superiors deigned to give him. As Simcoe so perceptively put it, "Nothing is more essential than to profess Correct Opinions unless it is to possess correct Acquaintances."

In his never-ending search for success, Simcoe eagerly appropriated other people's often questionable proposals. The concept of municipal incorporations was Cartwright's not Simcoe's. Lord Dorchester's order to reoccupy Ft. Miamis, which Simcoe at first opposed, was later claimed by Simcoe as his own and he boasted it had been the master-stroke that averted war. He had a tendency to support the wrong people as result of which he suffered many disappointments. Intent on succeeding in a world whose workings he often misunderstood, he sought so hard to please he became somewhat of a nuisance to his superiors.

Notwithstanding these shortcomings, Simcoe was "the most persistently energetic governor sent to British North America following the American Revolution. He had an articulate faith in Upper Canada's imperial destiny and a sympathetic appreciation of the interests and aspirations of its inhabitants." Simcoe served his king and his country with "a zeal exceeded only by his piety toward God." In no aspect of the service of this hectic hero was this zeal more real than in the hopes and aspirations he had for what he called, his "dream province." It was which was

In His Own Words

"destined by nature to govern the interior world."

He had great plans for this peninsular country that jabbed like a giant finger into the very heart of North America. Simcoe peered into the future and saw the great growth that lay ahead for the tiny colony. While a bold visionary whose prediction of the province's potential for development showed great perception, Simcoe lacked common sense, proportion and flexibility. His outlook and attitude lagged far behind those of other more far-sighted statesmen of the time. His failure to fathom the future of his 'dream province' is illustrated in his assurance to the British government that the province's possibilities would be infinitely greater than those of any other British colony only if it were populated by two classes of people: the haves and the have nots.

|

Simcoe pledged to preserve a society based on levels: a lower class that knew its lot in life and stayed in it and a titled, aristocratic, upper class that determined what that was. Egalitarianism had no place in his province. He denounced democracy, declaring it would be province's undoing. Democrats pandered to the mindless whims of the masses, republicans were nothing more than scoundrels and liberty was just another name for licence. "I equally deprecate the darkness of Despotism as the Lunacy of Liberty."

Simcoe's view of the world was Simcoe-centric. His zeal was inseparable from his ambition which was deliberate and calculating. He candidly admitted during the American Revolution that he chose command of the light company because it was "generally esteemed the best mode of instruction for those who aim at higher stations." As soon as he received the appointment to Canada he so ernestly solicited, he made a virtue of accepting it and began to look forward to being rewarded "with future trusts and more lucrative employments." He eagerly acted on a minister's slightest mention and was sure to shamelessly herald in his dispatches his devotion to duty.

The position as lieutenant governor of Upper Canada was not Simcoe's first choice. Despite his professed hatred of the new republic to the south, he longed to be Britain's first ambassador to the United States of America. In a letter dated the 16th March, 1791 to Evan Nepean, Under Secretary of War, Simcoe inquired whether the Embassy in the United States, "the original object of my wishes," might be open to him. He was curtly informed that it was not. Consequently, the sovereign's "trusty and well-beloved John Graves Simcoe" accepted the position as lieutenant governor of Upper Canada at a salary of 2000 pounds a year, the appointment to be effective on December 24th, 1791.

Simcoe was born on Feb. 25, 1752, the third of four sons and the only one to survive childhood. His father, John Graves Simcoe, Esq., captain of His Majesty's ship Pembroke, died of pneumonia en route to Quebec with Wolfe in 1759. According to one source, Simcoe senior had earlier been captured by the French and imprisoned at Quebec. While there he was supposed to have made a chart of the St. Lawrence River which proved invaluable to the fleet that delivered Wolfe to his date with destiny on the Plains of Abraham. No record has ever been found to confirm the capture of Simcoe nor the existence of his chart of the treacherous channel of the St. Lawrence River.

|

Young John was educated at the Free Grammar School at Exeter and Eton and attended Merton College, Oxford which he left without earning a degree. His passion and educational pursuits were focussed on the military. His ambition was to devote himself to professional soldiering and "from childhood had been taught to consider the military as the most extensive and profound of sciences." Even though opportunites abounded during his lifetime for service in the military, Simcoe was denied the opportunity of a career in his chosen profession. "Because of this Simcoe, the strong-willed, self-confident military autocrat, is really a tragic figure."

Simcoe's Military Journal recounts his service as commander of the Queen's Rangers in the American Revolution. In 1771 at the age of 19 he obtained a commission as ensign in the 35th Regiment. Five years later he went to war in America to fight the revolutionaries. His regiment arrived in Boston in 1775, two days after the Battle of Bunker Hill on 17th June, 1775. While taking part in the siege of Boston, Simcoe purchased a captaincy. His subsequent promotions were all based on merit.

The origins of the Queen's Rangers lay in the Seven Years War (1756-1763) during which France and England fought for possession of the New World. Initially, French-Canadian habitants and their Aboriginal allies achieved success employing guerrilla tactics against the red-coated regulars. To counter the French tactics Robert Rogers raised a company of rangers for the British, which he trained in woodcraft, scouting and hit-and-run warfare along the frontiers of French Canada. The regiment was given the name Queen's Rangers in honour of Queen Charlotte the wife of King George the Third. Simcoe was made major at the age of 25 and assumed command of the Queen's Rangers on October 15, 1777. Simcoe's princpal contribution to the ranger regiment was the formation of a mounted comapny which he called his "huzzars." The Queen's Rangers numbered about 400 and were largely Loyalists and deserters from Washington's army. While few in number the Queen's Rangers were an elite fighting force fighting used for reconnaissance and as outpost troops skirmishing in advance of the British army. They carried out a series of risky, skillful, successful engagements against the enemy without a single reverse, a record they maintained to the end.

|

They did escort and patrol duty around Philadelphia in 1777-8, fought in the Pennsylvania campaign, served as rearguard during the British retreat to New York (1778) and fought at Perth Amboy, New Jersey, where Simcoe was captured but freed in a prisoner exchange three months later(1779-80). They saw action in Charlestown, South Carolina in 1780, fought in the raid on Richmond, Virginia with Benedict Arnold, and took part in other raids in Virginia and in the Yorktown campaign during the years 1780-81. In the winter of 1779 Simcoe even made an attempt to capture George Washington. The Rangers last important action on June 26, 1881 was also their boldest and their best, climaxing a glorious career. Simcoe wartime renown as a light cavalry officer made the Rangers one of the most successful British regiments in the war. The Light Infantryman was proficient at scouting and skirmishing and more than a match for the Americans and their ruthless Indian allies. Shooting rapids in canoes and whaleboats, traversing swamps and snowshoeing through endless tracts of forest, British Rangers earned a reputation for resilience and resourcefulness as they adapted to the wilderness conditions of North America. Their development was a watershed in the history of irregular warfare.

|

Simcoe was an unconventional soldier in a time when armies followed strict and rigid manoeuvres. He insisted that the Rangers be "accoutred for concealment," the first British regiment to wear green uniforms for camouflage. He set little store by drill and personally oversaw the training of a small party of troops in the surprise tactics of today's commandos, the methods varying depending on the circumstances. His guiding principles were surprise, speed, and close combat because of the terrain and the weaknesses in musketry which he clearly recognized. He emphasized physical fitness and got astounding results from his 'infantry' which he later estimated marched an average of 145 kilometres per week in every kind of weather. One of his more startling requirements for the period was his insistence that the men bathe at every opportunity.

On one occasion Simcoe had his horse shot from under him and during 1776-1777 he received three wounds during campaigns on Long Island, in New Jersey and during the capture of New York. Each time he hastened to return to active duty and rapidly established a reputation as a daring, caring, competent officer, an energetic and skilled leader who readily inspired confidence and loyalty in his men who were regularly involved in successful operations. Once Simcoe and forty-two of his mounted Queen's Rangers were sent out as a scouting party. On hearing that one hundred and fifty American militia were nearby, Simcoe decided to attack. He sent his buglers to the right to sound the charge, while the rest of his small party advanced on the left. Then in a loud voice Simcoe ordered his light infantry of which he had none, to "Charge." Believing they were surrounded and about to be caught in the jaws of a pincer attack, the American militia took fright and fled. Simcoe's forces pursued them, killing and capturing twenty-eight at a cost of one ranger killed and three wounded.

|

During another incident Simcoe was dispatched with his Rangers to destroy a main depot of American military stores which was guarded by a large force of militiamen. Simcoe decided on a ruse to rout the Americans. He had his men light a great many campfires along the river bank on the opposite side of the Americans. The American commander, fearing Simcoe's forces represented the advance of the whole British army, abandoned the stores and retreated. Simcoe sent some men across in canoes to destroy the supplies.

During Simcoe's time here he took some time from the war to woo a young lady named Sarah 'Sally' Townsend. On February 14, 1779, Valentine's Day, Simcoe sent Sally a poem in which he extolled her beauty and his love for her. It contained three verses, the first of which is as follows:

"Fairest Maid, where all Is fair, Beauty's pride and Nature's care;To you my heart I must resign, 0 choose me for your Valentine!

Love, Mighty God! Thou knows't full well, where all thy Mother's graces dwell,

Where they inhabit and combine to fix thy power with spells divine;

Thou knows't what powerful magick lies within the round of Sarah's eyes,

Or darted thence like lightning fires, and Heaven's own joys around inspires;

Thou knows't my heart will always prove the shrine of pure unchanging love!" It is not known whether Sally shared Simcoe infatuation. If indeed she did their romance never had time to ripen, for that same year Simcoe was ambushed by rebels, captured and imprisoned for six months in the common jail at Burlington, New Jersey. During his imprisonment he was treated harshly and because of gruelling hardships he became quite ill. His one attempt to escape was foiled when the phoney wooden key he was using broke in a lock. John McGill, a fellow Ranger who was captured with Simcoe, offered to impersonate Simcoe asleep in bed so his commander could escape. However, escape was unnecessary because of his disability.

|

When Simcoe learned that Cornwallis had proposed the cessation of hostilities for the purpose of settling the terms on which his posts could be surrendered, Simcoe immediately dispatched a request to Cornwallis to permit his corps composed of Loyalists and some deserters - both the object of the enemy's persecution - to escape to some safe haven. The Americans did not consider the Loyalists in the same light as regular soldiers. and Simcoe feared for their lives if captured. To Simcoe's chagrin Cornwallis refused this request saying, "the whole of the army must share one fate." Few shared their fate, however, for some of the deserters were promptly executed.

It was suggested that Simcoe suffered an emotional collapse when his intrepid little unit suffered its first defeat when Cornwallis surrendered at Yorktown in 1781. During the surrender the colours of the Queen's Rangers were smuggled away and never did fall into enemy hands. Simcoe spirited them to England where they remained until they were acquired by Canada and today are on display in the officers' mess of the Queen's Rangers at Fort York. As the finest Loyalist unit the Queen's Rangers were awarded the title 1st American Regiment and enrolled in the British Army in 1782.

While Simcoe called the Corps "the terror of their enemies," it neither pillaged nor plundered but pursued a policy with the populace of consideration and conciliation. To be magnanimous and chivalrous in war was to Simcoe the natural thing to do. Simcoe demonstrated compassion to enemy soldiers, on one occasion warning an American sentry that he would be shot if he did not retire. To another American officer he cautioned, "You are a brave fellow, but you must go away." He saw no reason to kill unnecessarily. The Duke of Northumberland called Simcoe "brave, humane and honest" and these qualities are evident throughout his Military Journal.

|

|

Simcoe, Never a Vindictive Victor |

Simcoe was sent home on parole from which he was finally released when he was exchanged for an American prisoner of equal rank being held by the British. Simcoe's parole discharge stated that as British government ministers had "earnestly desired that Lieutenant-Colonel Simcoe on parole to the United States of America be released from his said parole, I do hereby absolve the parole." The parole was signed by Benjamin Franklin. The war had been a personal triumph for Simcoe, who was granted the rank of lieutenant-colonel. His military service with the Rangers made him a sincere friend of Loyalists, whose support of the sovereign during the fighting in the rebellious colonies greatly impressed him. He was appalled by the sentiments of some in Britain who seemed to have adopted the viewpoint of General Washington, that "the best thing the Loyalists could do was to commit suicide." In 1783 when the war was concluded by the Treaty of Paris, the Queen's Rangers left New York for Nova Scotia where the regiment was disbanded. Many of the regiment's soldiers and officers settled in New Brunswick. Simcoe subsequently persuaded several of them to join him in Upper Canada when he became governor of the colony.

Shortly after his return to England romance was in the air and Simcoe fell in love. Just how fervently Elizabeth reciprocated the feeling was never really clear. In any case Simcoe married Miss Elizabeth Posthuma Gwilliam, a wealthy young heiress and talented artist, whose sketches made in Upper Canada provided an important source of information about early life in the pioneer community. As an English squire and a landed gentleman, Simcoe considered himself as much an aristocrat as the proudest duke in England. He loved the monarchy and the aristocracy and he could not imagine a society without rank, privilege and hierarchy. In November 1790 he was elected Member of Parliament for the borough of St. Maws, Cornwall.

|

Simcoe was forty and had been unable to find active service since he was 30. Simcoe was motivated by a single-minded passion to distinguish himself in some way in the colonies and his appointment as lieutenant governor stimulated his natural enthusiasm and boundless energy. He breathlessly described to a friend his plans for the colony. "I am to have a Bishop and an English Chief Justice. I propose that the site of the Colony should be in that great peninsula between the Lakes Huron, Erie and Ontario. I mean to establish a Capital in the very heart of the country on the river Thames." He was overflowing with plans and proposals and was always impatient to implement his dreams for the Canadian colony. He was in a hurry to make history. He deluded himself with the will-o'-the-wisp idea that there could be a reunion of the lost American colonies, that somehow he could overcome the democratic demon and win thethe American rebels could be won back to the bosom of the king. For anyone in 1793 to believe realistically in the reunion of empire was to suffer a bizarre fantasy or display political gullibility of a high order. Like most other lower-ranking colonial officials, Simcoe magnified the importance of his office. He visualized himself as a kind of colony king, a sylvan sovereign who was determined that his new province would become a blend of aristocracy and democracy, a judicious mixture of the upper class and lower levels settlers.

|

A distinguished Frenchman, Le comte Rochefoucault, an early visitor to Upper Canada, who spent several weeks as Simcoe's guest, recorded many of his observations about the colony and its governor, including this description of his host. "But for his inveterate hatred of the United States, which he too loudly professes and which he carries too far, General Simcoe appears in the most advantageous light. He is just, active, enlightened, brave, frank and possesses the confidence of the country, the troops and all those who join him in the administration of public affairs. To these he attends with the closest application. He preserves all the old friends of the King, and neglects no means to procure him new ones. In his private life, Governor Simcoe is simple, plain and obliging."

A heavy-set, six-footer with the blunt appearance of John Bull, Simcoe was a solitary, aloof individual. He always referred to himself in the third person, and Mrs. Simcoe addressed him either as 'the Colonel' or 'the Governor.' While he had drive, energy and originality, Simcoe was also willful and headstrong and often had a misguided sense of reality. He could be kind and generous, or cruel and stubborn. He could be calm and sensible one minute, and outraged and bombastic the next, quickly taking offence at anyone who deigned to question his tenacity of purpose. The ideal qualities of occupants of the office of lieutenant-governor included flexibility, tact, discretion and empathy. Simcoe, like his successors, was largely lacking in all these characteristics.

Simcoe was an intellectual magpie, an impractical dreamer who became entranced with one glittering idea for a while, only to abandon it suddenly in favour of another often unrealistic scheme. His ambition outran his talents and his energy frequently exceeded his judgment. His conduct of administration was decidedly autocratic. With his vein of self-sufficient obstinacy, Simcoe never took kindly to contrary opinions, and at times was undoubtedly difficult to work with. His adamant determination was reflected in his favourite expression, "It is my unremitting endeavour."

Simcoe was actively disliked by some for his imperious ways. It was recorded by one resident of Upper Canada on October 1793, that "Governor Simcoe has quarrelled with his Council and is gone off to Toronto in a pet. Representations have been made to the King and Parliament against him and the people are murmuring very hard." Throughout his posting in Upper Canada, Simcoe's actions were frequently the subject of controversy, and some historians have expressed surprise that the colony faired as well as it did under his leadership. He had no end of ideas and from the moment of his appointment, he inundated his superiors with a deluge of plans and proposals, many unrealistic and unworkable in a new colony. As a result of his wild, galloping imagination, new plans and projects tumbled over each other in his restless and fertile brain. If Simcoe's energy and enthusiasm had been matched by commonsense and compromise, he might have met with more success and considerably less frustration and disappointment.

While Simcoe bristled at any opposition to his own authority, he thought nothing of using any opportunity to circumvent the decisions and directions of his superior in Lower Canada, Lord Dorchester. In Simcoe's opinion, Dorchester was old and bereft of ideas, while he was young and brimming with projects and strategic plans. He bristled with open irritation at the unimaginative officialdom Dorchester represented, with his dithering and interfering obstruction, and Simcoe regularly appealled over Dorchester's head directly to officials in London, who never reprimanded him for this insubordination.

Simcoe made his mission the reversal of the American Revolution, once declaring that he was prepared to "die by more than Indian torture"to restore the United States to his Sovereign. He settled for a less painful approach, however, by seeking to establish on the very doorstep of Yankee-land, a free, honest and exceptional British colony, which Simcoe believed would act like a magnet to Americans. By enticing them to come to Canada, he hoped to convert them into supporters of the sovereign, something that British military might had failed to do. Simcoe believed the American Revolution had been a conspiracy started by a minority, and that many "from across the line" were still loyal to their 'Old Father,' Simcoe's affectionate name for the King. He felt these misguided Americans could be won back to their former support for the sovereign. He had this in mind, when in June, 1792, he referred to the "wavering provinces of Maine and Rhode Island," which he fancied might reject the union and rejoin the king's company.

|

He considered that all who came to Canada were King's men, loyal and true, motivated by love not of land, but of Crown and Motherland. As is usual in human affairs, motives of the American immigrants were mixed. There were some half-hearted monarchists and more than a few covert republicans. To Simcoe republicanism represented all that was reprehensible and wicked, and he was determined to immunize Upper Canadians against the democratic disease seeping up from the south. Ironically, Simcoe, who was all Tory and totally against everything democratic and republican, depended largely on emigrants from the American republic to populate the province's vast, empty spaces. They were skilled men and women who helped create a colony of peace and prosperity that persisted until the War of 1812. They were also the very people most likely to be 'infected' by the political principles he so detested.

Simcoe was certain that the absence of nobility in the American model of government was the glaring omission which had resulted in the American Revolution. He was certain the existence of nobility in Upper Canada would ensure "a superior, happier, more polished form of government," and was determined that his government would include the presence of hereditary nobility to provide moral guidance and loyal leadership for the masses. This meant that Simcoe's associates would not be chosen from those "who kept but one table." The rules were clear for those who knew how to decipher them. To be included in the ranks of the ruling elite, breeding, respectability and the proper social bearing were basic requirements. Those who possessed these requirements inevitably came to the colony directly from England. Not even Loyalists were considered for this close-knit group. While Simcoe admired their courage and commitment to the crown, he believed they were contaminated by republican principles. Simcoe expected the role of the fortunate few would be reinforced by religion, but only as offered by the Church of England. It was the old Tory view that this church and only this church would support the aristocratic minority by preventing "dangerous thoughts" from taking hold in the minds of the many. Simcoe's pursuit of perfection was described by one historian as "an orgy of enthusiasm," by which he intended to establish a model of Mother England in the wastelands of Upper Canada, where Simcoe envisioned a mini-aristocracy with himself at the top.

Simcoe was a man with a mission and anxious to begin the great task of carving his new colony out of the wilderness. His hard work and dedication did establish a soundly founded colony and he served Upper Canada well, but not always wisely. His vigor was not matched by his vision, for his concept of the colony's future was faulty. Simcoe's scheme of government by the privileged few was destined to produce fatal results in later days. These ideals in a community imbued with the principle of democracy were doomed to failure. His dream was dashed by the very settlers he welcomed into the province. While they were eager immigrants, their pledges of allegiance to the king were often given for land, not loyalty. They brought experience, expertise, determination and drive, but they also brought deeply rooted democratic ideas. These ideals ensured that Simcoe's model of the mother land would never become a reality in Canada. Simoce's dream of an aristocratic colony collided with the rugged pioneer spirit of settlers bent on building a new nation. Their insistent demands for ever more control of their country resulted in frustration, fury, and finally rebellion and bloodshed.

During his term of office, Simcoe suffered numerous ailments, including malarial fevers, jaundice, migraine headaches and rheumatism. These reoccurred a number of times during his four years and it is suggested that the cause was what today is known as hepatitis, which he got from army cooking added to numerous other infections. On one occasion when he was extremely ill with a persistent cough, Mary Brant, Joseph Brant's sister, prescribed the root of sweet flag (acorus calamus) which relieved his malady in a very short time. His ills were not always so easily cured, however, and he continued to be plagued by both physical sickness and emotional disappointments. In addition to suffering from "a severe indisposition," Simcoe, one of two "prancing pro-consuls," had grown weary of the discord and disagreements he regularly had with the other pro-consul, Lord Dorchester. Finally on the advice of his physician, Simcoe applied for sick leave, approval of which arrived on July 14th, 1796. He was informed that the frigate Pearl would be at Quebec at the beginning of August to take him and his family home to England.

|

On July 18, 1796, Simcoe presided at his last Executive Council meeting. One of his final acts was to seek permission for an entry to be made in the Council Book.

In His Own Words"that the grant of two hundred acres made to his infant son, Francis in the neighbourhood of York, be part of the land to which Simcoe was entitled as Lieutenant-Colonel and Commandant of the late Queen's Rangers during the American war." It was on this piece of property during the winter of 1795-96 that the Simcoes constructed a chateau or summer home which they called Castle Frank. It was located on the brow of a steep and lofty tree-covered ridge between Castle Frank Brook and the Don River, near the present-day intersection of Bloor and Parliament Streets. Castle Frank had an outstanding view of the valley. Wild rice once grew in the river below, attracting geese every fall, and fishing parties would travel up from the lake by canoe to catch salmon. It served as a shelter from the heat and hungry mosquitoes of summer during the Simcoes' final months in Upper Canada.

Elizabeth Simcoe tells us in a diary entry dated October 29, 1794: "We went 6 miles by water & landed, climbed up an exceeding steep hill or rather a series of sugar loafed Hills & approved of the highest spot, whence we looked down on the tops of large trees. There are large pine plains around it, which being without under wood I can ride and walk on and we hope the height of the situation will secure us from mosquitoes."

|

|

Castle Frank |

In the midst of the original white pine, elm, basswood, and butternut forest, the house was built of carefully hewn, squared and grooved logs that were clapboarded. The 30 by 50 foot building was oblong in structure, the longer side fronting on the south. The façade was meant to imitate a Grecian temple with its columns made of the trunks of four, sixteen-foot, well-matched, peeled pine trees supporting the portico that was formed by the projection of the roof. There were four windows on each side of the cottage with the main entrance at the front. The windows were shuttered with large double planks, heavily studded with the heads of thick, stout nails. The chimney was located in the centre of the roof. The inside finish of the structure was rough and never fully completed, but the large, open room was the source of much delight and the scene of numerous social occasions in the tiny settlement. The castle was named after their first son, Francis Gwillim, who was killed in his 22nd year in April, 1812 at the siege of Badajoz during the Peninsula War in Spain. Francis was buried on the field of battle. Elizabeth used Castle Frank as a summerhouse and country retreat, going up the Don by sleigh in winter or through the woods in summer for picnics and parties.

After the Simcoe's departure from Upper Canada, the cottage was used as a temporary home by the new Administrator, Peter Russell. Careless fishermen burned Castle Frank to the ground in 1829, leaving charred wood and rusted nails to mark its lovely location. This property, along with all the other Simcoe property in the province, was eventually sold off by the family. John Scadding managed the estate for a while, and purchased a portion of the land. In 1844 his son donated some of the property for St. James Cemetery. Much later, Sir Edward Kemp built a second, twenty-four-room Castle Frank, north of the original site. It was demolished in 1962 to make way for the present Rosedale Heights Secondary School. Today, a road, a crescent, and a subway stop perpetuate the name Castle Frank.

Thursday afternoon, July 21st, the Simcoe's boarded the schooner Onondaga, and with a soft, summer breeze filling its sails, they left the little capital for the last time and headed for Kingston. In the forest that fronted the colony's capital of York, they left behind for all eternity, a precious part of themselves - their 15-month old, Canadian-born daughter Katherine. The tragic news of the "melancholy event" was sent to Mrs. Hunt in England, who forwarded a grave marker inscribed: "Katherine Simcoe, January 16,1793- April 19, 1794. Happy In the Lord." Katherine was buried on Easter Monday in a tiny grave in a military cemetery situated east of the huts of the Queen's Rangers which Simcoe had named Fort York.

|

|

Onondaga |

|

|

Final Resting Place of Katherine Simcoe |

The location today is Victoria Square Memorial Park on Portland Avenue.[*]Surviving memorial stones have been placed in the centre of the square and if one is Katherine's her name is no longer visible. The cenotaph located there was constructed in memory of officers, non-commissioned officers and men who were killed, died of wounds and disease in the following regiments or companies of regiments engaged during the war of 1812-1815 upon the western Canadian frontier, west of Kingston.

The Simcoes arrived at Kingston on July 25th, and after an 18 hour stopover continued on to Montreal where they arrived on the 30th. Thence to Quebec City where Simcoe spent the next six weeks carefully completing the official affairs of the province, after which he enjoyed "a very pleasant period" awaiting the arrival his ship, the Pearl which the Simcoes boarded on September 10th. Their eventful trip home included a pursuit

|

by a French frigate and a brig commanded by an American named Citizen Barney. They outran their pursuers, however, and arrived safely off the Downs of England on the 13th of October and at 1:00 o'clock that day docked at a place called Deal some eleven miles northeast of Dover.

Simcoe's interest in and concern for his precious province did not cease with his departure. On March 26th, 1798, he wrote to the King urging him to watch over Upper Canada.

In His Own Words

"It will be with proper and honourable support the most valuable possession out of the British Isles in population, commerce, and principles of the British Empire."

Only once did Simcoe express a desire to return to Canada and that was when he believed the Duke of Portland had promised him the governor-generalship, but even then he wanted a peerage as well. Instead Simcoe was assigned to San Domingo, now known as Haiti. He departed in January 1797 and returned the same year because he was frustrated by the failure of the government to provide the troops and supplies which he felt were necessary. Ill also from from the few months in a disease-ridden climate, Simcoe returned home in August. On 9th of January 1806 he attended the funeral of Lord Horatio Nelson at St. Paul's Cathedral. He found the ceremony impressive but "too theatrical."

Simcoe was promoted to major general and then lieutenant general in 1798 but never again received an operational command. During the invasion scare of 1801 he was entrusted with command of all forces in the most endangered sections of England's south coast. In 1806 he was made Commander-in-chief, India. At age 54 fame seemed at last to be within his grasp. Before taking up this post, he was dispatched along with another commissioner to the court of Portugal to assist Britain's oldest ally against Napoleon. He rather than the Duke of Welllington might have received command of the Anglo-Portuguese forces but fate intervened.He fell ill on the outbound voyage and was returned home immediately dying at Torbay. Despite he faithful service to his sovereign, Simcoe was one of the few British lieutenant-generals of that time not knighted. He died plain John Graves Simcoe on October 25, 1806.

|

|

John Graves Simcoe |

Simcoe lived his life in accordance with the legend graven upon the family coat of arms:

NON SIBI SED PATRIAE

(NOT FOR SELF BUT FOR COUNTRY).

The words of the Duke of Wellington could well have served as Simcoe's personal motto: "I have ate of the King's salt and, therefore, I conceive it to be my duty to serve with unhesitating zeal and cheerfulness when and where my King or his government may think proper to employ me."

|

|

Victoria Memorial Park |

Only seventeen head stones are intact from the original cemetery, none of which is matched to the corresponding remains below ground. At the turn of the last century, a monument was finally raised to commmorate the dead. The designer of it was Walter Allward, who also designed the massive amd magnificent war memorial at Vimy Ridge.

[*]Victoria Memorial Square Restoration ProjectThe old military burial ground at Victoria Memorial Park at Portland and Niagara Streets [a few blocks north and east of Fort York in Toronto] is the first European cemetery in the City of Toronto. It was created in 1793 by Lt. Governor John Graves Simcoe shortly after the establishment of the Garrison at York and the founding of the town. The cemetery was located a short distance north-east of the garrison and on the east side of the Garrison Creek. It provided a burying ground for soldiers of the Toronto Garrison and their dependants. The first burial to take place in the cemetery is considered to be that of Katherine Simcoe, infant daughter of Lieutenant Governor John Graves Simcoe. Katherine died in 1794. Marcus Van Steen, in his book, Governor Simcoe and His Lady, recounts the death of Katherine and states that a year after her demise, a small marble tombstone, brought from England arrived and was placed over the child’s grave with the following inscription.

“Katherine Simcoe

January 16. 1793 - April 19, 1794

Happy in the Lord

In 1869 a cabinet order transfering the property along with 17 other sites was approved by Governor General Lord Elgin, Prime Minister John A. Macdonald, Georges Etienne Cartier, Macdonald's Minister of Militia, and seven other members of Macdonald's cabinet. The order stated the sites were put under "the charge, keeping and management of the minister of the militia and defence for the defence of the dominion until further ordered." In 1939 the City of Toronto formally assumed care of the park and graves for a reported $1 a year. After lobbying the federal government for years to turn the site over to the city, Prime Minister Harper's government on Friday July 4th, 2008, confirmed its transfer, telling the Canadian Press, "there is no longer an operational requirement" for the defence of the country, the site has been sold to the City of Toronto. [Toronto Star, 7 July, 2008]

Copyright © 2013 Website Administrator