foreword | Historical Narratives | Resources | Links | Contact

KILLER CHOLERA

History is post-mortem.

Reports regarding the scourge cholera are often in the news for the dread disease still haunts refugee camps around the world. Early in the 19th century the disease was rampant throughout continental Europe and residents of Great Britain prepared themselves for its appearance on their island.

Precautions were taken in London to protect the population from this plague and it was peremptorily pronounced that preparations to prevent an epidemic had been prompt and complete. There was, intoned the Times "No atom of alarm." Not all citizens shared the confidence of London's great newspaper and they awaited with feelings akin to terror the arrival of the grim scourge. Their fears proved well-founded for cholera morbus did invade the British Isles. "Death rode triumphant through every street," and swept through the city like flames through straw. Before the plague had mercifully moderated thousands of people had died.

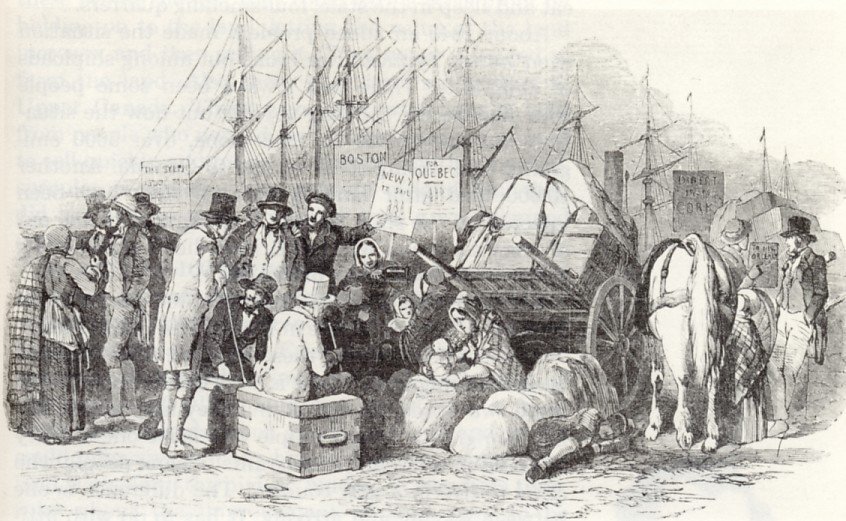

From Great Britain the pestilence was carried to Canada by impoverished immigrants seeking a new life in a new land.

|

|

Preparing to Depart for Canada |

|

|

Leaving for Life in a New Land Called Canada |

They travelled across the ocean in overcrowded ships in which they were forced to live in dreadful filth and squalor. The long and frequently treacherous Atlantic crossing meant that many in steerage spent from five to twelve weeks in dark, dank, cramped, unsanitary holds which were described by one traveller as "filthy, filled with a fetid stench and containing hundreds huddled together like animals."

|

|

|

Under the British Passenger Acts ships sailing to Quebec were allowed one adult or two children for every 1.1 square metres of steerage space. Each adult was allotted a sleeping space of 1.8 metres in length but only 46 centimetres in width. These regulations were often ignored since most ships carried far more passengers than regulations allowed. Weakened by seasickness and suffering from dysentery and cholera caused by lack of clean water, shiploads of infected passengers arrived in British North America. Thus cholera came to Canada in 1832 bringing "a very great mortality of hasty death."

To signify that a ship carried passengers who were infected with the disease a yellow flag was raised on the mast. Waving ominously in the wind it forewarned one and all to beware. Regulations forbidding visits to these vessels were easily enforced for the pestilential pennant was deterrent enough.

From south to north hath the cholera come,

He came like a despot king;

He hath swept the earth with a conqueror's step,

And the air with a spirit's wing.

Initially it was thought that cholera was a disease of the "lower classes," since they were the ones who were always hardest hit by it. Society was shattered to discover, however, that the disease began to occur among the "better sort." Only then was attention given to the disease by government officials. Boards of Health immediately sprang up and hastened to offer warnings and words of advice. Citizens were cautioned to avoid over-exertion, anxiety and sudden changes in diet and to keep out of the night air. They were also cautioned to keep clean, wear flannel and have plenty of anti-cholera medicine on hand. The latter was a homemade brew that was a mixture of laudanum (opium) and brandy. Neither the message nor the 'medicine' was of any help.

The word 'cholera,' which comes from an old Greek word for 'gutter' is most appropriate for it is caused by improperly disposed of human wastes. The bacterium Vibrio comma is a screw-shaped, one-celled organism equipped with a very mobile, terminal, vibrating tail - hence its name. Contaminated drinking water produces a toxin in the small intestine which makes the wall of the stomach more porous to water. This causes vomiting and massive purging of liquids resulting in de-hydration which upsets the body's chemical balance. Other symptoms include severe spasms and cramps, great thirst, a husky voice, a sunken face, blue colouring and eventually as the body processes collapse kidney failure.

The disease struck suddenly and arbitrarily and depending on the individual, cholera's effects could range from minor intestinal disturbances to severe illness which was painful and rapidly fatal. A person in good health at daybreak might be dead and buried by nightfall. If one wanted to wish anyone bad luck or ill-will, a common curse of the day was "May cholera catch you."

Based on the false assumption that cholera was contagious the Canadian response to the anticipated onslaught of immigrants in 1832 was to establish a quarantine station on Grosse Isle, a small, hilly island thirty miles below Quebec City. It became the first landfall in Canada and ships' pilots on the St. Lawrence were ordered to anchor all vessels there for examination by health officers. While the ship was being "purified," poorer passengers in steerage were required to clean themselves and their baggage. Wealthier passengers in cabins were exempted from the purification process but this made little difference since the sources of water were often the same and the healthy quickly became infected.

In Montreal and Quebec City schools and shops were closed and the only booming businesses were the ones producing the one-inch thick boards needed for coffins. Smoke from fumigation fires cast an ominous pall over every neighbourhood. Fifty-two thousand people emigrated to Canada in 1832 and they overwhelmed the facilities set up to receive them. Because cholera was contracted by ingesting water or food contaminated by those with cholera, quarantine alone could not hope to contain the disease. In spite of the quarantine sheds set up along the river, primitive conditions prevailed among the throngs that surged up the St. Lawrence River carrying cholera with them into Upper Canada.

Ships travelling from York to Queenston were instructed to stop at the mouth of the Niagara River for inspection. Most captains did not want their vessels identified as "infected" so they frequently ignored these directions. When one vessel named Canada approached the wharf at Niagara, a mob armed with clubs shouted, "We're not going to be infected," and tried to prevent the ship from landing. Its captain complained later that "the lowest orders of Niagara" had taken the law into their own hands. However, the town officials who were sympathetic tended to endorse their violent action.

Local municipal governments were largely responsible for dealing with cholera and individual communities acted in a variety of ways to protect themselves from the epidemic. Boats were banned from landing and travellers were prevented from entering towns. In some places armed guards were stationed on roads to keep out strangers. Strong measures were debated at Niagara to bar the entry of workers from Lundy's Lane and Chippawa where twenty men had been stricken and eleven died. On July 25, 1832 magistrates at Niagara ordered all crafts to wait fifty yards off shore for inspection by medical officers. When one of its crew members became sick and died the vessel Niagara was ordered fumigated with a mixture of burning tar, sulphur and chloride of lime.

Boards of health were created to deal with the crisis and they had varying degrees of success. The massive number of immigrants complicated the situation because overcrowding in poor housing, unsanitary living conditions and inadequate supplies of clean water simply perpetuated the problem. In some instances fear of contracting the disease was so great that no one was willing to retrieve the dead for burial. Bodies were placed inside shanties which were set ablaze so that fire consumed them.

Homeowners were ordered to disinfect their premises with lime and to whitewash houses, cellars and privies. Few followed through on these directions and even when lime for whitewash was provided free of charge there was limited response to the appeal. Fines for non-compliance were levied but these were largely uncollectable.

In the midst of the infection military bases were oases of safety because when sanitary measures were ordered they were obeyed. At Fort George, for example, drains were repaired, pools of stagnant water were drained and all buildings were cleaned and whitewashed. When diseases did strike, the forts attempted to isolate themselves from nearby communities. As a result the military suffered relatively little during an epidemic.

Eventually it was realized that cholera could best be prevented by ensuring a clean supply of water and that the disease could best be treated by simple rehydration techniques. Cholera came to Canada again but never as severely as in 1832. Even then the actual impact of the disease was less than many were led to believe. As the Toronto Patriot editorialized, "We verily think that in 1832 the press killed more on this continent than cholera."

Copyright © 2013 Website Administrator