foreword | Historical Narratives | Resources | Links | Contact

TECUMSEH

History is the essence of innumerable biographies.

"He died a martyr to his cause and left his bones upon the earth for which he fought."

|

|

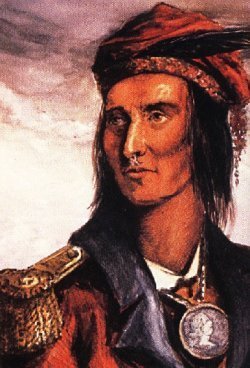

Tecumseh |

"Sell a country! Why not sell the air, the clouds, the great sea as well as the earth?" So raged the great Shawnee chieftain, Tecumseh, the 'Shooting Star' who flashed forth onto the northwest frontier pledging to protect Native traditions and territory, for he knew once their land was lost their freedom would follow.

Some three hundred years ago in the forests and fertile valleys along the Ohio River, two cultures collided. In the area called the Old Northwest, European traders met and eventually mastered the Indian people with phantom weapons, diseases against which they had no defence. From the frenzied fighting that took place in this forest empire between Natives and the newcomers emerged an unforgettable leader known by name Shooting Star, the great Tecumseh.

Tecumseh was born in 1768 in Piqua, a village along the Mad River about five miles west of present-day Springfield, Ohio. The fourth of eight children. Tecumseh grew into a strong, courageous, intelligent brave whose skills in the art of guerrilla warfare made him a menace to those who fought him. Wise in the ways of forest flora and fauna, he used camouflage to beguile, confuse, confound and elude pursuers, and the cries of birds and four-footed creatures to signal and surprise his enemies. His tactics were based on speed and ambush - the sudden strike, the wild war whoop that daunted and demoralized, followed by the terrible tomahawk. Among the Indians who survived the fight at Fallen Timbers was the dreamer Tecumseh whose father was slain by the Long Knives at the battle of Point Pleasant on the Ohio.

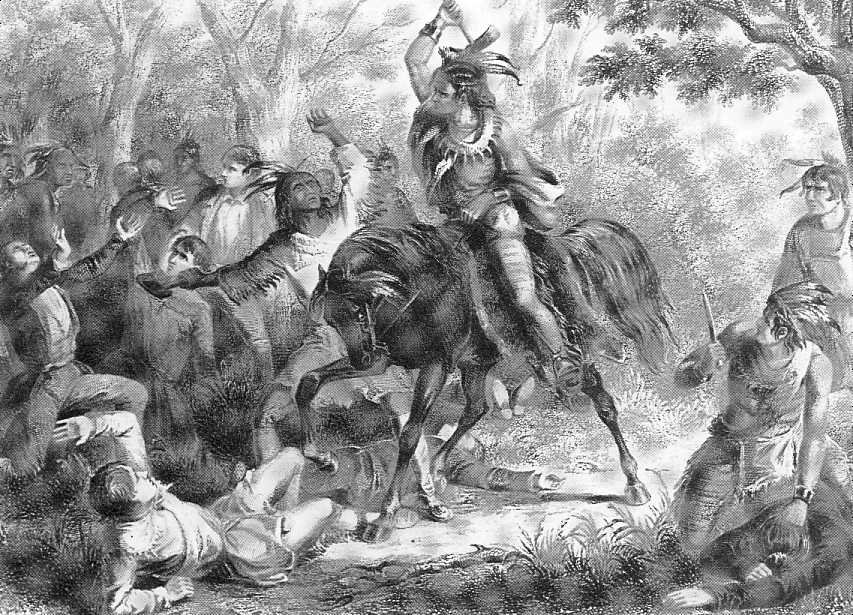

His eldest brother, Cheeseekau, raised him to be a sharp fighter who looked "with contempt on everything that was mean." Tecumseh was a man of intelligence, eloquence, courage and character, a relentless enemy but a merciful victor to captives. He was respected and held in high esteem by friend and foe alike. While fierce and fearless in warfare, Tecumseh was an honourable opponent. Ever "merciful and magnanimous," this "gallant and impetuous spirit" learned idealism and compassion from his brother and was never savage or sadistic to his captives. When no less a personage than Isaac Brock said of him, "A more sagacious or gallant warrior does not exist," he was speaking of one of the continent's unforgettable sachems, perhaps, the most lauded Aboriginal leader in North American history. Tecumseh had a passionate concern for his people with a genius for strategy. Brock believed that if he had been British, he would have been a great general.

|

|

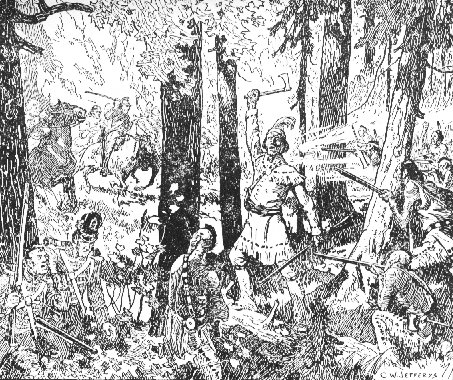

An enraged Tecumseh saving the lives of white's facing a fate worse than death at the hands of his own people. |

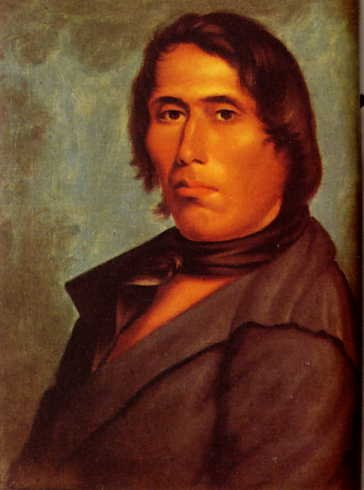

Tecumseh quickly acquired a reputation as a stand-firm chief preoccupied with people rather than things. The handsome, charismatic sachem was described by a British officer as "being in appearance and noble bearing, one of the finest-looking men I have ever seen." He was five feet ten inches in height but seemed taller because he walked proudly erect with a graceful, athletic stride. His skin was the colour of light copper and his face oval with fine features and his black, piercing eyes gave him an exceptionally wild and impressive appearance. When most Natives had adopted the clothing of white man, Tecumseh wore a plain deerskin hunting shirt over deerskin pantaloons, his moccasins ornamented with porcupine quills and his jet black hair adorned with a single eagle feather.

This buckskin-clad statesman had an eloquent tongue. He could speak English but on public occasions used his native tongue and never failed to amaze American and British officials with his fiery, forceful fluency. His eloquence was edgy, figurative, concise and cutting. Tecumseh's speeches were described as a cascade of past events passionately recounted with sharp reasoning and soaring poetry. His oratory drew crowds eager to hear speeches marked with dignity, eloquence and pride.

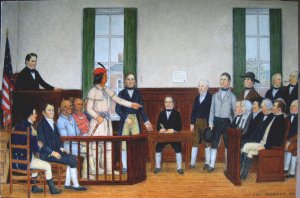

These were tense times in Ohio and in 1807 Americans there feared the ever-increasing numbers of Natives congregating in Greenville. As their apprehensions mounted, there was growing pressure on officials to act. Some cried for war to drive this menace from their midst. Governor Kirker kept his head and instead invited Native leaders to meet with him and others at Chillicothe. Four chiefs accepted his invitation and the day after their arrival, they attracted anxious crowds to the courthouse. The chiefs in turn addressed the large and anxious audience. Tecumseh was one of the speakers and a witness remembered his decisive effect.

When Tecumseh rose to speak, he cast his gaze over the vast multitude. He was one of the most dignified men I ever beheld. Words fell from his lips swiftly and forcefully. While this witness from the wild was speaking, the crowded room was hushed; it was a most profound silence. Carefully and confidently, Tecumseh spoke of the Indians' willingness to adhere to the treaty and live in peace and friendship with their white brethren. His welcome words were received with much gratitude and good will by the whites and settlers immediately returned to their farms.

|

|

Tecumseh Mesmerized the Many |

On another occasion after speaking to a large group of Aboriginals and Americans, Tecumseh was invited by William Henry Harrison, governor of Indiana Territory from 1800to 1812, to join him on the portico of Harrison's home. When told by the interpreter that "your father requests that you sit beside him," Tecumseh snorted in derision. "My father! The Great Spirit is my father and the earth is my Tecumseh decided to dedicate his life to defending the property of his people by preventing the sale of land by any tribe thinking of trading their homes and heritage for trappings and trinkets. mother and on her bosom I will repose," whereupon he seated himself on the ground.

During the discussions that followed, Tecumseh angrily denounced the latest Indian land cessions and raged against the readiness of some chiefs to give away land that belonged to all Indians. In the heated exchange, Harrison, fearing trouble from the assembled Indians, who loudly supported Tecumseh's outburst, drew his sword. Fortunately, cool heads prevailed and violence was averted. After parting from Harrison, Tecumseh headed south certain that, "the northern and southen tribes must join together in a unified front against the Long Knives."

|

|

Tenseness between Tecumseh and Harrison |

Tecumseh had a great grasp of history and exhibited an astonishing knowledge of treaties. He knew details of hundreds of them and cited chapter and verse to prove that most had been violated by white men. No voice ever challenged his facts. The unceasing flow of white men whose numbers were like leaves on the trees grieved and dismayed Tecumseh. "We are made miserable by the white people who are never satisfied and are always encroaching on our land. They have driven us from the great salt water, forced us over the mountains and would shortly push us into the lakes. We are determined to go no further." As Tecumseh watched the land on which his people had lived for thousands of years traded away by tribes for trifles, he decided to assume the role of a trans-tribal leader and undertook to create a pan-Indian alliance to resist the white onslaught. The older sachems, electrified by Tecumseh's call to arms, recognized him as their solitary spokesman.

To take up the cause as savior of his people, Tecumseh secretly set out to weld together not only the northern tribes but also those along the Mississippi Valley into a fighting force strong enough to resist the white man's assaults on Native lands. He envisioned forming a union fanned by the flames of anger and animosity towards the whites whose insatiable demand for ever more land threatened their very existence. He decided to dedicate his life to defending the property of his people by preventing the sale of land by tribes willing to trade their homes and their heritage for trappings and trinkets. Rumours spread quickly about his determination to forge a 'pan-Indian confederacy' in the Old Northwest, His legendary diplomatic forays took him great distances.

In his travels Tecumseh gained the support of the Potawatomi, Ojibwa, Shawnee, Ottawa, Winnebagos and the Kickapoo. Accompanied by an entourage of Shawnee, Kickapoo and Winnebago warriors, the Shawnee chief was on the last leg of a mission that had taken him three thousand miles in six months. Beginning in the summer of 1811 he had travelled south from Indiana to spread his message of intertribal unity. Night after night he had stood before council fires exhorting the southern nations to bury their various and long-standing grudges and prepare for a collective war against the whites to defend what remained of their tribal lands that were being lost to the United States at an alarming rate. Control of the continent was seen as a fundamental right of the young republic. Bursting its national boundaries, the new nation overflowed into the western lands resulting inevitably to confrontation and conflict with the indigenous tribes that since time began had inhabited these regions.

The Treaty of Greenville had resulted in the tribes of the Old Northwest Territory ceding to the whiteman millions and millions of acres of land and by 1805 the entire north bank of the Ohio River had seen the last of the tribes and their teepees, lost forever to the people of plains and the forests.

Tecumseh, who saw the handwriting on the wall, timed his visit to Tuckhabatchee in what is now Alabama to coincide with the annual council of the Creek Confederacy comprised of some fifteen different tribes that included Chickasaws, Choctaws and Cherokees. Whenever Tecumseh urged the tribes to unite in a grand confederacy against the white man, he always addressed them in a dignified language, making an impassioned appeal which "touched the hearts of his dusky audiences." He stood for several minutes surveying the assembled warriors before he spoke. "Brothers, We belong to one family. We are all children of the Great Spirit. We walk in the same path and slake our thirst at the same spring. Now affairs of the greatest concern lead us to smoke the pipe around the same council fire. My people are brave and numerous, but the white people are too strong for them alone. If you do not unite with us they will first destroy us and then you will fall easy prey to them. We must be united. We must smoke the same pipe and fight each other's battles."

For all his passion and power, Tecumseh's speeches met with mixed effectiveness. Some who listened remained aloof. He had little success with the Delaware, Wyandot, Menominee, Miami and the Piankeshaw among others and his messianic message fell flat among most of the Creek who felt betrayed by the British peace with the Americans. They saw no reason to support their former enemies, while others were reluctant to ally themselves with the British. Tecumseh's success was greater among the younger warriors; older chiefs tended to oppose him on the grounds that his proposed intertribal council would undermine their authority. Despite these holdouts, however, Tecumseh's influence and that of his brother, Tenskawatawa, called 'The Prophet' spread.

Tenskwatawa also travelled from tribe to tribe never mincing his words. "O Shawnee braves, O Potawatomi men O Miami Panthers O Ottawa foxes, O Miami lynxes, O Kickapoo beavers, O Winnebago wolves, lift up your hatchets, raise your knives, sight your rifles. Have no fears; your lives are charmed. Stand up to the foe. Fall upon him. Wound, rend, tear, flay scalp and leave him to the wolves and buzzards." They listened spellbound to the compelling oratory of Tenskwatawa and to his brother, Tecumtha. The Britsh became interested and the Americans apprehensive. |

|

'The Prophet |

Harrison had ample opportunity to assess his adversary and he was more than impressed. He reported to the Secretary of War Eustis, "If it were not for the vicinity of the United States, Tecumseh would perhaps be the founder of an empire that would rival that of Mexico or Peru. No difficulties deterred him. His activity and industry supply the want of letters. For four years he has been in constant motion. You see him today on the Wabash and in a short time you hear him on the shores of Lake Erie or Michigan or on the banks of the Mississippi and wherever he goes he makes an impression favourable to his purposes. He is now up the last round to put a finishing stroke to his work."

Harrison could see that a clash was coming and he commenced taking measures to meet it. He was determined to strike a blow of his own in Tecumseh's absence and establish a presence in the disputed land. So when Tecumseh was in the south rallying support for his confederacy, Harrison moved north. On September 26, 1811 Harrison and his force of more than 900 officers and men marched to the Wabash to repel any attack. It took them two weeks to travel sixty-five miles to the high ground where Terre Haute now stands. Ahead lay territory disputed by Tecumseh and the site of his capital of sorts, called Prophet's Town, near the confluence of the Wabash and Tippecanoe Rivers. Prophet's Town had become a symbol of Indian resistance and the rallying Tecumseh's confederacy. Harrison made up his mind to destroy Prophet's Town. With Tecumseh absent and Harrison's militia bolstered with some trained regulars, there was no time like the present to rid the frontier of this centre of Indian resistance.

Tenskwatawa had been warned by Tecumseh to avoid any confrontation with the whites while he was away. However, Tenskwatawa resented the silent menace of the American military and its impudence in camping so contemptuously close to their home. He was also under pressure from the hotheads in his camp. He saw this as an opportunity to display his leadership abilities and at the same time defeat the threatening American force. After the Prophet's incantations had confirmed the enemy's gunpowder had turned to sand and his bullets to soft mud, Tenskwatawa and his assembled warriors moved warily through the murky darkness to assault Harrison's camp. His plan was to attack at the approach of dawn.

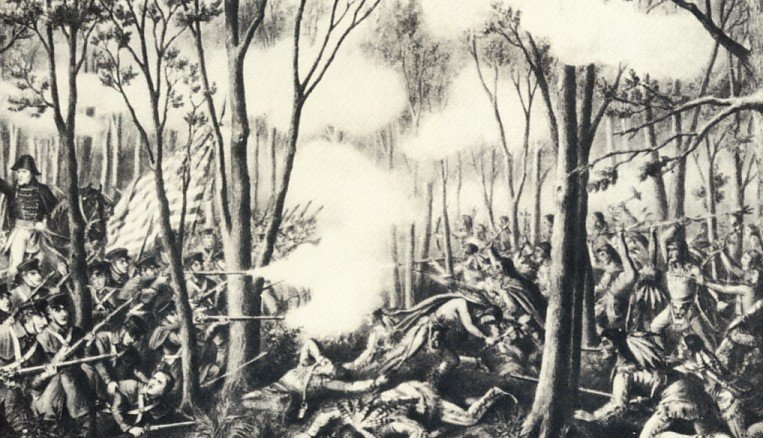

Tenskwatawa's first assault included black-painted, hand-picked warriors intent on killing Harrison and his officers. When one of the warriors was spotted by a sentry, he fired a shot to alert the camp. Harrison had suspected the possibility of a surprise attack and had ordered his men to sleep "on their arms." As the troops awakened and reached for their rifles as the main assault began. Fighting broke out everywhere as the two forces fell upon each other. Volleys of bullets were fired on the illuminated camp as some of the soldiers shot blindly into the darkness while others hurried to extinguish the bonfires that made them easy targets. The main body of warriors surged foward into point blank range, the rifle flashes like fireflies in the pre-dawn darkness.

|

|

Confrontation at Tippecanoe |

They attacked in wave after wave against Harrison's defensive perimeter. During the battle the Prophet stood on a slight rise singing his war songs. His assurances of invincibility were soon proven false and before long he and his disorganized and disheartened warriors, their ammunition dwindling and retreated to Prophetstown. When Harrison marched late on November 8th, the town was deserted. After taking any items of use, the Americans put the torch to five thousand bushels of corn and beans and all of the lodges. As the flames flared into the sky, Harrison declared his forces had achieved an unqualified victory. The Battle of Tippecanoe, he trumpeted, was a triumph for the United States.

|

|

Battle of Tippecanoe |

The battle had been less a victory for Harrison than a personal defeat for Tenskwatawa. The winter's store of staples was gone and the village lay in ashes. Thanks to the Prophet's wild indiscretion, Harrison had accomplished his objective and made his enemy appear the aggressor. Tenskwatawa's credibility was gone and never again wouldhe command the respect, admiration and awe of the tribesmen. For his disastrous defeat, the Prophet earned nothing but scorn, anger and disdain from his brother when he returned from the south to find his capital and dreams of a confederacy in blackened ruins. While he had had some success in calling for a confederacy of the clans, it proved impossible even for him to tranform a myriad of tribes into a viable whole. Now all was at an end. Tecumseh's schemes had been frustrated for good by the folly of the Prophet.

The site of the battle has since become classic ground and is enclosed by an iron fence. Tippecanoe, as the battle was named, was a relatively minor military skirmish but it had great ramifications. It shattered Tecumseh's dream of a Native confederacy, destroyed The Prophet's mystical authority and drove Tecumseh to declare his allegiance to King George. Americans looked at the battle through rose-coloured glasses and saw a victory which transformed Harrison into a war hero. Later this led to cries of "Tippecanoe and Tyler Too," the campaign slogan which carried Harrison as president and John Tyler as vice president into the White House in 1840.

|

|

William H. Harrison |

|

|

John Tyler |

|

|

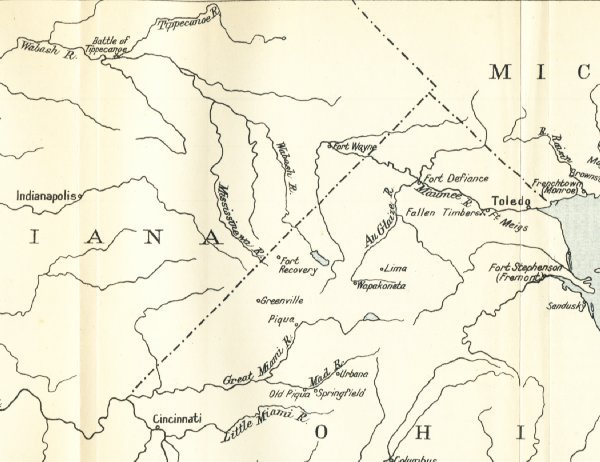

Tecumseh's Country [western tip of Lake Erie on the right]

|

On July 1 Tecumseh crossed into Canada and committed himself and his followers to the British cause. The first meeting between Brock and Tecumseh took place by lamplight in a chamber of Fort Malden. They made an impressive pair. Brock, a tall, barrel-chested, auburn-haired man with a keen blue gaze and a ruddy complexion, wore a scarlet frock coat with bullion epaulettes. Tecumseh was described as a pre-possessing figure, his complexion light copper, his countenance oval with bright hazel eyes beaming energy and decision. Three small crowns or coronets were suspended from the lower cartilage of his nose and a large silver medallion bearing the likeness of George III was attached to a mixed coloured wampum string hanging about his neck. He was dressed in his signature fringed deerskin shirt and leggings, and moccasins adorned with porcupine-quill ornamentation. Brock immediately crossed the room to shake his hand. "Two strong men stood face to face, though they came from the ends of the earth."

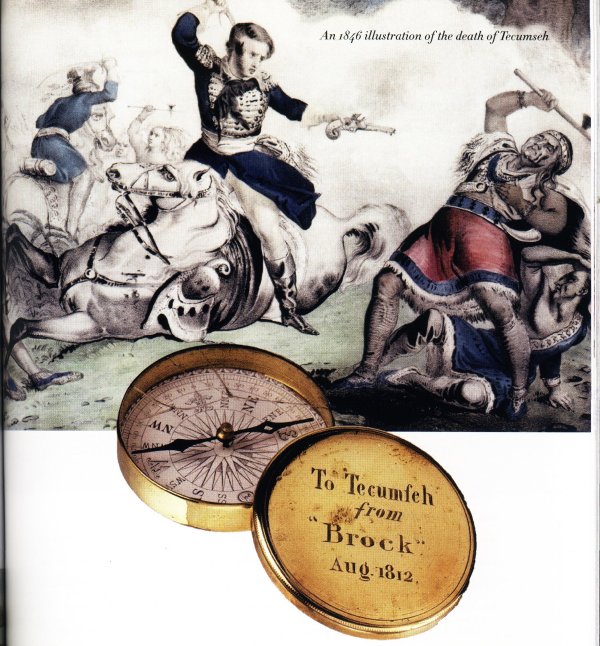

After much discussion about whether to attack Fort Detroit or not - Brock's officers were dubious and some against - Brock ended the discussion with that they would attack. Tecumseh turned to the other chiefs present and said, "Ho!" Pointing a finger at Brock he cried, "This is a man!" After the surrender of Detroit, Brock, with one of his instinctive gestures, slipped off his richly tasselled scarlet sash and fastened it about Tecumseh in the presence of the troops and Native braves. The Shawnee in return presented Brock with an arrow-patterned Indian sash. When the fatal bullet hit Brock later that year, he was wearing the sash Tecumseh had given him.

Fort Meigs was constructed on the Maumee River upstream from the site of the abandoned British post of Fort Miami and just across the river from the site of the Battle of Fallen Timbers. Harrison considered it easily defended and a logical place to deposit men and materiel. It was also a thorn in the side of the British should they contemplate any major advance from Detroit. General Henry Procter, who had been left in command of Detroit by Brock following its capture, thought so too and encouraged by Tecumseh he decided to attack it in the spring of 1813. With 900 regulars and militia, supported by 1200 Indian allies led by Tecumseh, Procter sailed up the Maumee to the ruins of Fort Miami and laid seige to Fort Meigs. The bombardment proved ineffective with the Americans recovering the cannon balls and firing them back at the British.

A perplexed Procter took a page from Brock's book and demanded the Americans surrender. Harrison was not Hull, however, and rejected Procter's demand. Time dragged on and Procter's militia units became anxious to return to their farms for spring seeding. Unaccustomed to prolonged warfare and weary of fighting, the greater part of Tecumseh's braves returned to their villages. When a relief force arrived to bolster Harrison's beseiged fort, Proctor withdrew down the Maumee. A second attack by the British and Tecumseh's warriors two months later ended with Procter falling back following a tentative assault. Tecumseh was enraged at what he considered Procter's premature withdrawal and his admiration for Brock became contempt for Procter. In a rage Tecumseh declared that Procter was unfit to command and should "go and put on petticoats." He compared Procter to an animal that when frightened "dropped his tail between his legs and runs off." These caustic comments did not augur well for future relations between the British commander and his principal ally.

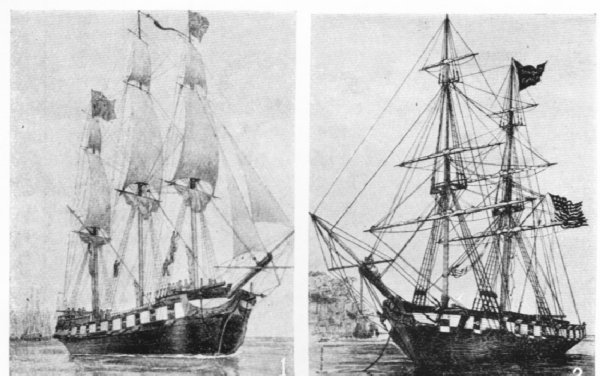

The hope of the British now centred on their fleet which commanded Lake Erie. A grey morning mist rolled up from Lake Erie when the British fleet stood out in battle array. Captain Robert Barclay, one of Nelson's heroes at Trafalgar was in command. Like the great admiral under whom he served, he had lost an arm in naval conflict, a fact that earned him the Indian title, "our father with the one arm." The American fleet was commanded by Captain Oliver Perry. A light breeze rippled the surface of the lake and filled the swelling sails as action began about noon. The roar of Detroit's twenty-four pounder resounding across the lake told the anxious observers on shore that the battle had begun. The savage encounter raged for three hours before Barclay, his thigh badly broken, his shoulder severely shattered and all his officers either killed or wounded, was compelled to yield to a superior force with double the weight of metal.

|

|

Barclay' Flagship Detroit & Perry's Flagship Niagara

|

The American naval victory on Lake Erie threatened Procter's position, effectively cutting him off from supplies and reinforcement. Feeling vulnerable to attack and believing he did not "see the least chance of occupying to advantage my present position," Procter decided to withdraw to the Thames River without delay. At a council of war on September 18, Tecumseh raged against withdrawal. In a thundering declaration delivered with flashing eye and rapid gesture, he argued that foes were fought by attacking, not fleeing, "Father, you have the arms and ammunition which our great father sent for his red childdren. If you intend to retreat, give them to us and you may go. Our lives are in the hands of the Great Spirit. We are determined to defend our lands, and if it be his will, we wish to leave our bones upon them." Tecumseh saw that the great purpose of his life was about to fail.

Procter countered that the fort had been dismantled to equip the Detroit, that the hospital was full of sick soldiers and that starvation was staring them in the face. He said the place to fight was along the Thames River five miles below Moraviantown. Tecumseh had no choice but to reconcile himself to retreat. Procter proceeded to abandon Detroit, Fort Malden and Amherstburg with the Americans in hot pursuit, streaming across the Detroit River and occupyng Amherstburg and its shipyards. At dawn on October 5, 1813 Procter turned to face his pursuers. Instead of concentrating his forces, Procter spread his sick, hungry, dishearted soldiers along a wide, thin front, his left flank protected by the river and his right by a cedar swamp.

Tecumseh and some 1000 warriors held Procter's right flank from the outer edge of the small swamp to the thickets of a larger one several hundred yards further inland. When all was in readiness, Tecumseh passed down the British line, all eyes watching the familiar figure in its tanned buckskin. In his belt was his silver-mounted tomahawk and his knife in its leather case. He went up and down the line of British soldiers offering encouragement and pressing the hand of each officer. Whatever doubts were in his mind, he maintained the dignity of a warrior to the end, endavouring to instil courage in the hearts of all about him. Setting aside his anger, Tecumseh turned to Porter and shook his hand for the last time, saying simply. "Father, have a big heart. Tell your young men to be firm and all will be well."

|

|

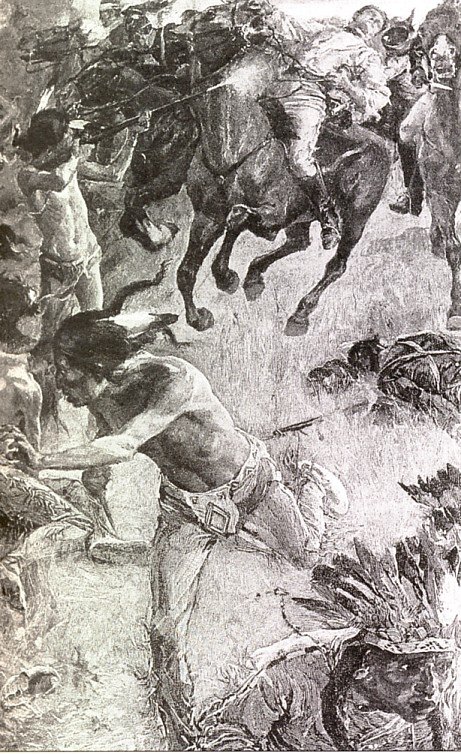

Tecumseh & Procter |

The so-called Battle of the Thames was hardly a battle at all. Harrison arrived on the scene at 8 a.m. and prepared for the attack. His intention was to order the bulk of the militia to strike Tecumseh between the two swamps while he led his troops along the river to engage Procter's units. Before this plan could be implemented, one of his officers suggested an alternative. Noting how thin the British line was, he suggested to Harrison that the cavalry make a frontal charge into the line. Harrison agreed and the plan was implemented. The attack on the Briitish line came in mid-afternoon and broke it almost at once. The first wave of horsemen severed the thin red line, then proceeded to dismount and fire on the backs of the British, while a second wave poured on fire on them from the front. The shock of the galloping horsemen overwhelmed the wavering line and before long the British surrendered. Procter salvaged the colours of the 41st Regiment and made his escape to Moraviantown abandoning his men to their own devices, an act for which he was later court-martialled.

The Americans now swarmed forward to meet the Native warriors and a fierce battle ensued. The fought in the tangled thicket. Tecumseh in fringed deerskin leggings and shirt with a sash tied around his waist, rode in an out among his warriors, firing his rifle and inspiring his men. With red and black war paint, his fierce resistance spurred the braves who fought valiantly against the larger, better-equipped American force. A shot was fired and Shooting Star fell to the earth. As he did so wrote one of the American soldiers, his warriors "gave one of the loudest yells I have everheard from humn beings and that ended the fight." With Tecumseh's death the Indian confederacy in the northwest died as well.

On Procter's arrival at Ancaster on Burlington Heights, he faced another fight, this one for his honour and reputation as an officer. At a subsequent court martial, Procter was condemned for his failure to fight and his flight from the 41st Regiment, "its well earned laurels tarnished and its conduct calling loudly for reproach and censure." One wonders what might have happened had Brock instead of Procter stood with Tecumseh at the Battle of the Thames.

|

|

The Compass Brock Gave to Tecumseh & An Ilustration of Tecumseh's Death |

A major reason for the tension in Upper Canada in 1794 was the unrest of Native tribes in the Northwest Territory. They were on the warpath because of the encroachment of Americans on Aboriginal lands. From George Washington's time onward, Americans used every opportunity to thrust the Native tribes westward in their relentless drive to acquire ever more land. Native peoples were pressed inexorably to abandon their homes and heritage in the face of the insatiable demands of American settlers for land. As Robert Hamilton stated in a letter dated January 4th, 1792 to Simcoe

In His Own Words"The Americans seem possessed with a species of mania for getting lands which has no bounds. Their Congress, prudent, reasonable and wise in other matters in this seems as much infected as the people."

While NativeS could not stem the flood of white newcomers who multiplied at such a staggering rate, they did strike back in anger at the white onslaught using large-scale violence. In addition to set-piece conflicts there was the risk of skirmish, ambush and slaughter of both whites and Natives. Raids on the settlements wreaked vengeance on white squatters. Americans attributed much of this mayhem to the subversive activities of British Indian agents urging the Aborigines on and keeping them well supplied with guns, ammunition and war paint. They completely ignored their own cavalier contempt for boundary treaties solemnly signed by their leaders and the sachems. The raids seemed anarchic and mindlessly cruel, but cruel as they were as war always is they were less mindless than the message written in blood and flame.

In addition to being charged with fostering frontier fighting in the west, Britain was faulted for its failure to relinquish the northwest posts on American territory. Both these irritants festered in the minds of Americans and as terror and tensions grew, it appeared to many that the two countries were poised on the brink of war. In these tense times, the friendship of Native warriors was very important. Both Britain and the United States vied for the allegiance of the various tribes, sparing neither energy nor expense to win them over. In New York this included paying a dollar a head to Iroquois braves, who were invited aboard a French ship to see the guillotined semblance of Louis XVI's severed head dripping blood. Britain had Joseph Brant's leadership to thank for keeping the Six Nations true to the King's cause. Both countries contrived in every way they could, to create jealousies and divide Native loyalties. Washington charged that Britain was

In His Own Words

"Seducing tribes that we have hitherto been keeping at peace at a heavy expense and who have no cause for complaint."

Despite Britain's close friendship with Brant and the tribes of the Six Nations, William Johnson, British Superintendent of Indian Affairs, admitted that fair and equitable treatment of the Aborigines was difficult to provide, because it frequently conflicted with the interests of leading men in the province. Merchants with investments in land speculation as well as local sheriffs and justices of the peace hindered government efforts to secure just treatment for the Aborigines.

Although land was bought and treaties were signed by British officials, the land deals were often defined in the vaguest of terms. For example, northern boundaries were determined by how far a person could walk in a day or by how far one could hear the sound of a gun fired from the lakeshore. The First Nations received very little for the immense tracts of land they ceded. In 1784, the Mississaugas gave up 3 million arcres along the Niagara Pensinsula for less than 1200 pounds worth of gifts. British negotiators were always cautioned "to pay the utmost attention to Economy."

The increasing loss of their land to white settlers was a source of continuing concern to the chiefs of the various tribes. They were aware of the ongoing negotiations between the American John Jay and his British counterpart, and they eagerly awaited the terms of the treaty, hoping it would include provisions to protect them and their lands from further encroachment by whitemen. They waited in vain for while the treaty referred to Aboriginal trade, it omitted any mention of Aboriginal property rights. The Natives had backed the losing side and were now at the mercy of whites on both sides of the border. Many tribes saw the extinction of their way of life "written on the wind."

While they readily admitted that Native warriors had bled freely for the King, the British proceeded to sacrifice the interests of their Native allies to the cause of accommodation with the Americans. If the Aborigines now intended to confront the Americans to preserve what was left of their lands, they would simply have to shift and shoot for themselves. In the United States an important source of government revenues came from the sale of land to settlers. This was land purchased for a pittance from the Aboriginal owners. As time passed tribal chiefs became less willing to sell their lands to scheming individuals for mere baubles and beads. The Americans were quick to realize this. "It is no secret that the Indians are beginning to appreciate their lands, not so much for the use they make of them as by the value at which they see them estimated by those who purchase them."

As a consequence this realization made the purchasing land from the Aborigines more complicated and costly. As a result some American government agents make deals fraudulently with renegade representatives of the tribes, or bribed chiefs with dollars and drink to get them to make their mark on official documents. Often land speculators simply claimed the Aboriginal lands before government agents had completed their negotiations and then provoked the Aboriginals to do something about it. When warriors responded with force to protect what was theirs, the army was called in to "rescue"the American interlopers. Defeat usually followed and the chiefs were then forced with punitive treaties to sign away their lands. This pathetic pattern was repeated throughout the period of American's westward expansion.

"The Indians should be made to smart," declared the American general Arthur St. Clair. Congress agreed and appropriated a million dollars for a federal army to fight the western tribes. St. Clair marched to the Wabash River southwest of Lake Erie where he met a force of Shawnees and Miamis and was severely defeated. This convinced the American government that the union of the western tribes had become too powerful to ignore and stronger forces would be required. Prior to any military action, however, half-hearted negotiations usually preceded the use of force in order to convince public opinion at home and abroad, as Jefferson put it,

In His Own Words"that Peace was unattainable on terms the Indians would agree to."

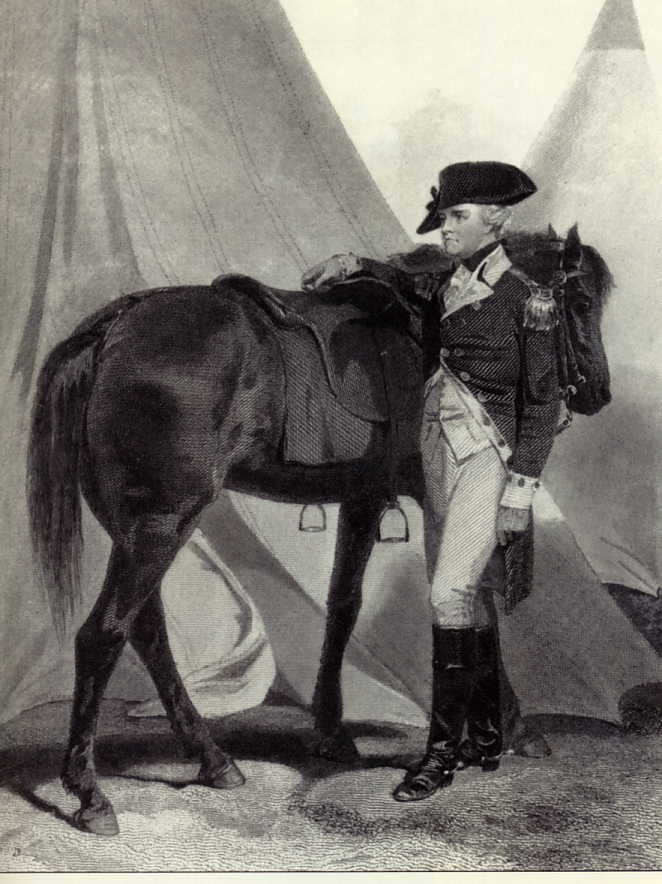

When an important peace parley failed American commissioners sent the following coded message to a waiting general."We did not effect peace." The general translated this into "Begin vigorous offensive action." The offensive action occurred at a place called Fallen Timbers on August 20th 1794. The army of Brigadier General Anthony Wayne, the Natives' nemesis, met and defeated a large force of western Natives. The Miami chief, Little Turtle, was a fierce opponent of the Americans but by the time of this battle he advocated peace.

|

|

Brigadier General Anthony Wayne |

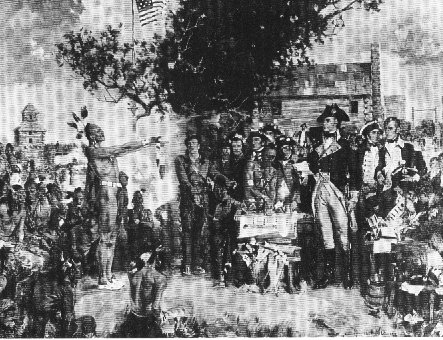

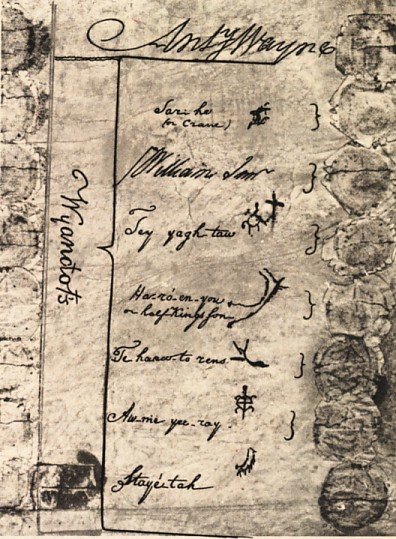

Subsequent to this defeat some 110 chiefs and warriors signed the Treaty of Fort Greenville in August 1795. By this treaty, the most important in the history of the United States, the sachems and War Chiefs gave away 25,000 square miles which today includes most of present-day Ohio, part of Indiana and the sites of Detroit, Chicago and a number of other mid-western cities for a measely 25,000 dollars in trade goods - calico shirts, farm tools, trade hatchets, ribbons, combs, mirrors and blankets and an annuity of $9500 to be divided among the tribes. It was a humilitating settlement for the payments represented a mere pittance with some tribes receiving as little as $500 a year. Few could challenge its terms, however, for when Wayne destroyed their fields, most of the destitute Natives became dependent on the United States for food. The situation and the ceremony were mocked. When a calumet or peace pipe was smoked by the parties to finalize the terms of the treaty, the ceremony was ridiculed by one American negotiator as "a tedious routine."

|

|

Signing the Treaty at Fort Greenville |

|

|

Treaty of Fort Greenville |

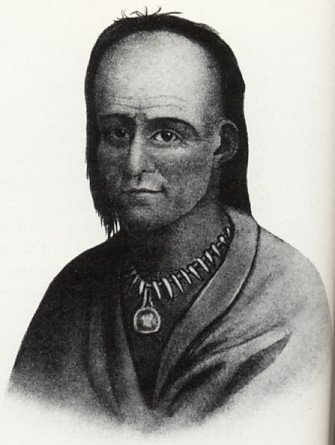

In August 1795 after weeks of negotiating with General Wayne, Little Turtle and other leaders representing tribes of the Northwest signed the Treaty of Greenville. This agreement opened vast new lands in the West to American settlers. (The symbol of Little Turtle is next to the bottom.)

|

|

Little Turtle, Miami Chief |

From a pre-contact population in the millions, the number of Native peoples remaining by 1900 numbered some 250 thousand. Their dispossession makes melancholy reading. The grim truth was that when two peoples competed for the same land, the stronger prevailed and the weaker simply had to accept whatever terms they could get. In return for this huge tract of the fertile frontier, pledges were given by the American officials that the remaining lands would be left to the Native owners. Even as they made this pledge they knew it would never be kept, for the great tide of white settlement was unstoppable.

Joseph Brant, Chief of the Six Nations, hoped it might not be too late to salvage something.

In His Own Words"I know that to complain of what is past will not ensure an absolute redress, but I believe it may be useful to reflect upon past errors and to discuss the malconduct of public officers whereby important injuries have been done to Indians."

Others like Chief Cornplanter thought it was already too late.

In His Own Words"Brothers, we have scarcely place left to spread our blankets. You have taken our country."

Alone among the sachems the great Shawnee Chief Tecumseh refused to sign the treaty. Tecumseh was a man of remarkable intelligence and ability. Noble in speech and behaviour, this great orator was farsighted, brave and merciful towards his captives.

In His Own Words"So live your life that fear of death can never enter your heart. Seek to make your life long and its purpose in the service of your people. Show respect to all people and grovel to none. When you rise in the morning give thanks for the joy of living.

Tecumseh raged against the sale of lands long held by the Aboriginals. "Sell a country! Why not sell the air, the clouds, the great sea as well as the earth? Did not the Great Spirit make all for the use of his children? Our fathers from their tombs reproach us. I hear them wailing in the winds. We are determined to defend our land, and if it be the Creator's will, we wish to leave our bones upon it."

|

|

Tecumseh at the Battle of The Thames |

Tecumseh did just that. With painted face and tomahawk held high he fell fighting from a load of buckshot in the breast near Moraviantown at the Battle of Thames. So died one very brave heart. With his death effective Native resistance south of the lakes practically ceased.

Tecumseh's people revered him as the white men venerated Brock, but their grieving saw no flags lowered, no martial music mourned his death, no stately monument marked his final resting place. To this day conflicting stories are told about what happened to Tecumseh's remains. Some accounts say the American troops mutilated the great chief's body where it had fallen. During the years that followed, the chief's memory was exploited by those who claimed to have slain the great Tecumseh.Not the least of these was a Kentucky Democrat named Richard M. Johnson, the most likely candidate, capitalized on his reputation as Tecumseh's killer to win the vice presidency of the United States in 1837. When prompted by the oft-repeated question whether he had, in fact, killed Tecumseh, an exasperated Johnson said, "They say I killed him; how could I tell? I was in too much of a hurry when he was advancing on me to ask him his name or inquire of the health of his family. I fired as quick as convenient and he fell."

|

|

Tecumseh |

Shawnee tradition holds that Tecumseh's compatriots temporarily buried him stealthily by the light of flickering torches intending to return later for his remains. His grave was quickly blanketed by the falling autumn leaves and supposedly lost forever in the mists of time. Not so say his people. As sunset faded into darkness his faithful warriors stole like spirits through the woods and bore his body away. According to a Shawnee story, "No white man knows or will ever know where we took the body of our beloved Tecumseh and buried him." No trace was ever found of Shooting Star.

"Slowly and sadly we laid him down,

On the field of his fame, red and gory,

We carved not a line and we raised not a stone

But left him alone in his glory."

Tribute to Tecumseh

(author unknown)

Gloom, silence and solitude rest on the spot

Where the hopes of the red men perished.

But the fame of the hero who fell shall not

By the virtuous cease to be cherished.

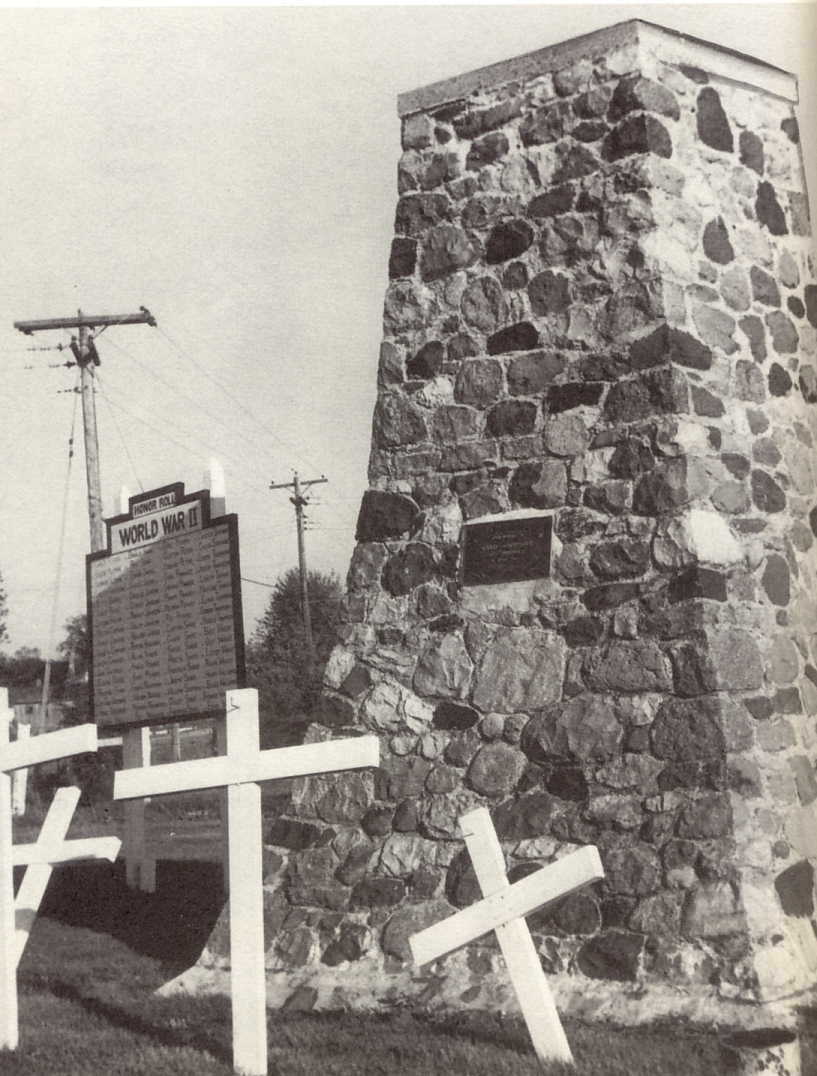

In 1931 a Grand Council approved a resolution declaring that bones preserved on Walpole Island were, in fact, the actual bones of Tecumseh. Whether they are or not no one can know for certain. Money was raised and the bones buried under a simple monument which overlooks the St. Clair River at the junction of the main road to the Island and River Road.

|

|

Tecumseh's Walpole Island Cairn, |

|

|

Commemoration of Tecumseh by the National Historic Sites and Monuments Board 5 October, 1963 |

In June 2003 on the Chippewas of Kettle and Stoney Point First Nation reserve, a monument featuring four life-sized bronzed statues honouring First Nations veterans was unveiled. One of the bronzed figures is of the great chief Tecumseh, "who was killed while fighting alongside British troops in 1813 against American invaders about 45 minutes from the reserve." The statues, which include a First Nations servicewoman, a Canadian soldier and an American soldier are set atop a giant turtle representing the Earth and the long life of Native peoples.

Tecumseh never had the opportunity to demonstrate his leadership in peacetime. He was the product of one of the most critical periods in the history of American Indians and from birth to death was involved in conflict and war. Designated by one historian as "the most extraordinary Indian that has appeared in history," Tecumseh looked beyond the mere resistance of a tribe or group of tribes to white encroachment. He fought to give all Indians a national rather than a tribal consciousness and to unite them in a common homeland where they might continue to dwell under their own laws and leaders. Today this is called self-determination and it supported by the United Nations.

Tecumseh pointed to the United States as a model for the many Native tribes to emulate. He said the states had set an example by forming a union among all the fires (states). Why then should they castigate and comdemn the Aboriginals for following it. Tecumseh's failure to confront the crisis effectively threw all the tribes back upon their separate resources re-establishing the same pattern individual tribes had used since the beginning of their conflict with the whiteman. Thus they sought unsuccessfully to cope with the foreign interlopers.

It is impossible to cast Tecumseh as a Canadian patriot. His loyality was never to Canada. It was a dream of a pan-Indian movement that would secure for his people the land necessary for them to continue their way of life. The few months he spent fighting with British forces were in service to that vision.

In his poem Tecumseh Charles Mair gives this description of the primeval days of peacefulness on this continent before the arrival of the Europeans. "The passionate or calm pageants of the skies

No artist drew; but in the auburn west

Innumerable faces of fair cloud

Vanished in silent darkness with the day

The prairie realm - vast ocean's paraphrases -

Rich in wild grasses numberless, and flowers

Unnamed, save in mute Nature's inventory

No civilized barbarian trenched for gain."

"Sleep well, Tecumseh, in thy unknown grave,

Thou mighty savage, resolute and brave;

Thou master and strong spirit of the woods,

Unsheltered traveller in sad solitudes,

Yearner o'er Wyandot and Cherokee,

Could'st tell us now what hath been and shall be."

Copyright © 2013 Website Administrator