foreword | Historical Narratives | Resources | Links | Contact

SIMCOE'S ARRIVAL AT NIAGARA

History is a pattern of timeless moments.

The frustrating delays ended at last, and early on the morning of June 8th, 1792, the Simcoes, with servants and children in tow and accompanied by Aides-de-Camp Lieutenants Grey and Thomas Talbot, passed through St. Louis Gate at Quebec City, walked to the river and embarked for Upper Canada in batteau and canoe.

|

Three weeks were spent in Kingston, where Simcoe's inauguration took place in St. George's Church, a ceremony that saw oath-taking by Governor Simcoe and three member of his Executive Council: William Osgoode, James Baby and Peter Russell. Kingston's citizens believed their town would become the capital of the new province. It was after all a military and naval base, the largest western settlement by far in Upper Canada, and easily accessible from east and west by both land and water. Even Lord Dorchester had recommended Kingston as the colony's capital. Nevertheless, residents were still nervous about Niagara being selected because they suspected Simcoe was intent on making it the colony's capital. In a final desperate act to prevent this from happening, they tried to discredit Niagara by citing shortages there of everything from provisions to accommodations. They even warned about the fetid air that rose from the River Niagara that caused ague, a malaria-like illness that regularly reoccurred with fever, chills and perspiration.

It was all to no avail. Simcoe considered Kingston an unsatisfactory site for the new capital. Not only was it dangerously exposed to the United States, but more importantly as far as Simcoe was concerned, it had been recommended by Lord Dorchester. Time would reveal that the sovereign's senior Canadian officials could agree on very little, and Simcoe had no intention of sanctioning Dorchester's suggestion for his new colony's capital. Despite the dire warnings and the earnest entreaties, Simcoe announced he would be moving on to Niagara. Especially indignant at Simcoe's choice was Kingston's leading merchant, Richard Cartwright, a Loyalists, who had served at Fort Niagara during the Revolution.

Simcoe chose Niagara, which he promptly renamed Newark, as his capital. It was central. Water-borne transport was the best means of travel and the tiny settlement was easily accessible from various directions. It had been settled in an orderly manner by members of Butler's Rangers, who provided an immediate source of military might if needed. Its safety was furthered ensured by the cannons across the river at the British bastion in Fort Niagara. The Niagara River was the gateway to the West via the four great lakes and the Ohio and the Mississippi Rivers. On the east bank of the river Fort Niagara served as the guardian of this vital passage and thus of Forts Detroit and Michilimackinac on the upper lakes. While Fort Niagara, which was known to the Aborigines as the French Capital, was within the territory of the newly formed United States of America, it was still occupied by British troops, and Simcoe fervently hoped it would continue to be so.

|

|

'The Castle' Fort Niagara |

At eight o'clock in the morning on Monday, July 23rd, 1792 Simcoe set out for his capital. He had expressed a wish to make the trip around the lake in a row boat, but his officials persuaded him otherwise. It would be, they said, "tedious and dangerous." (Not to mention tough on those who had to do the rowing!) Simcoe was accompanied by his coolly competent wife, Elizabeth, who often acted as his secretary. She carefully scrutinized the country, meticulously describing and sketching their surroundings. Over four years she created a wonderful record of life around them, her speedy and spontaneous watercolours provide dozens of early videos of the newly born nation. They boarded His Majesty's armed vessel the Onondaga, a topsail schooner built near Gananoque in 1789-90. it carried six guns, a crew of 14 men and was commanded by Commodore David Beaton, naval officer in charge of armed vessels on Lake Ontario.

|

|

Onondaga |

|

|

Onondaga Plaque |

The vessel set sail in a gentle breeze, but had travelled only some seven miles when the wind dropped and the Simcoes found themselves becalmed in the clear blue waters of the lake. Mrs. Simcoe was impressed by the "beautiful transparency" of the water, through which she could see the bottom of the lake. After a short delay, a fair wind rose which permitted them to resume their trip. Mrs. Simcoe suspected seaman on the lakes had little nautical knowledge and her suspicions were confirmed when they very nearly struck a shoal.Tuesday was wet and windy. Wednesday the 25th was clear and cold, but they made little progress because "the wind was contrary." At a distance of some forty miles from their destination, they saw a great cloud rising into the clear, blue sky, and were amazed to learn it resulted from the Falls of Niagara. The great cataract had ten times today's volume and it created a pillar of white cloud that reached almost to the stratosphere.

|

|

A View of Niagara Falls |

Later when they reached shore, they discovered that the ground shook from the falling water that funneled into the strait from the three of the largest Great Lakes. The Simcoes could hardly contain their excitement at the prospect of seeing for themselves the Mighty Thunderer about which they had heard so much. Mrs. Simcoe, an accomplished and accurate artist was eager to sketch and paint this grand natural phenomenon, which Simcoe later described as "the stupendous wonder of this country." He enthusiastically informed his superiors in London that it was worth a trip across the Atlantic Ocean just to view the magnificent cataract.

|

|

Scarborough Bluffs |

As they travelled along the shore of Lake Ontario, Mrs.Simcoe spied a sight that reminded her of the heights of her home in Scarborough, North Yorkshire. She named it Scarborough Heights now Bluffs after that English town, This section of England;s coastline was the only one bombarded by German battle cruisers in the first world war. This occurred on 16 December, -----, when ships of the German High Seas Fleet encountered ships of Britain's Grand Fleet on the edge of Dogger Bank in the middle of the North Sea.

|

|

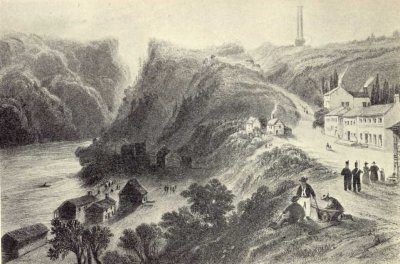

Navy Hall, Niagara from the river, 1792 |

At nine sharp in the morning on Thursday, July 26th, the King's representative docked at his little capital. The arrival of the regal couple caused a great stir in the little hamlet at the mouth of the Niagara River. Regiments of the regulars, Butler's Rangers and militiamen received him with military pomp. [*] People from town and country welcomed him with loyal addresses and shouts of welcome. The town was hung with flags and bands of the regiments made the air resound with martial music and God Save the King. Aborigines of the Six Nations headed by Captain Brant in colourful regalia greeted the new governor with hearty howls of welcome.

|

|

Thayandenagea Joseph Brant |

Booming about them was the welcoming roar of cannons from vessels in the river, answered by guns guarding the ramparts of Fort Niagara.

|

|

Cannon Cascade for Simcoe |

Simcoe had finally arrived at the capital, a tiny town in the wasteland wilderness of Upper Canada to which the Simcoes' by their very presence would bring a degree of regal dignity and style to the newly named capital. They softened somewhat the tough, taxing lives of the settlers by exposing them periodically to enjoyable diversions provided by the distinguished guests who visited the Simcoes. During this period, Simcoe's aide, Thomas Talbot, became a very close friend of the family and regularly endeavoured to ease the discomforts and difficulties for Mrs. Simcoe. Talbot treasured his time with the Governor and his family, and later fondly recalled the parties they "had that happy summer of 1792, when we were all young and gay and frequently dined sumptuously on whitefish caught by the soldiers in the river."

By the Treaty of Paris in 1783, the eastern side of the Niagara River had been ceded by Britain to the United States. Nine years later, however, Fort Niagara still remained in the possession of British troops. In addition British garrisons occupied other fortified posts at Oswegatchie (now Ogdensburg), Oswego, Presqu'ile (now Erie), Sandusky, Detroit and Michilimackinac, all on American territory. Britain justified retaining control of these northwest posts ostensibly because of the republic's repudiation of its promise to reimburse the Loyalists for their losses. The real reason had more to do with Britain's fears of losing direct contact with the Native peoples and the Great Lakes' fur trade which flowed from that contact. Britain was also apprehensive about the possibility of a Native rebellion launched by angry Aboriginal chiefs protesting the breach of British guarantees that Native lands would remain theirs, when, in fact, the British had ceded these lands to the Americans.

|

Thomas Jefferson, who was then the American Secretary of State, raged against Britain's failure to withdraw its garrisons from these posts on American territory. He regularly reminded the British ambassador that it would be done, in the words of the peace treaty, "with all convenient speed." Jefferson fumed that Britain's failure to live up to this commitment meant that the treaty ending the revolutionary war "was violated in England before its contents were widely known in America."

|

|

Thomas Jefferson |

Simcoe and the settlers in the scattered settlements that embraced these forts, waited "with anxious hearts and hopes" for word of Britain's intentions regarding the future of the important interior posts. In a letter written in 1789 to Sir Evan Nepean, Under Secretary of War, Simcoe warned that "should the Forts be given up the loss of Canada must surely follow." Simcoe was strongly opposed, in particular, to Britain forfeiting control of Fort Niagara to the Americans. Fur traders and Aborigines warned Britain of the severe consequences of abandoning the old south-west.

|

For a short period of time, Britain hoped that with the help of the Native tribes they might even be able to modify the boundary terms of the treaty. But when the western tribes failed to defend their hunting grounds from encroaching Americans, it was recognized that Britain would have to relinquish the posts, for if the Americans were determined to have them, they would simply take them when they were strong enough to do so.

Jay's Treaty, signed by both countries in November 1794, settled the problem. In accordance with its terms, Britain agreed to withdraw its garrisons from the western posts and did so in the summer of 1796, when the red-coated regiments marched out of them forever. When the Americans took possession of Fort Niagara, Upper Canada's capital at Newark would have been at the mercy of its menacing cannons in the event of hostilities. As a result the colony's capital would have to be relocated. In 1792 the future of the fort was still in doubt, and until a final decision was made as to its ownership, Newark continued to serve as the colony's capital.

|

|

John Jay |

Simcoe's personal choice as capital of the colony was the present city of London. He selected the Forks of Thames as the ideal location of the capital of Upper Canada before he left England. even before there was an Upper Canada. Early in 1791, he wrote to Sir Joseph Banks, President of the Royal Society:"I mean to establish a Capital in the very heart of the country upon the River La Tranche." Simcoe made his first trip to the Forks in 1793 on his way back from a visit to Fort Detroit which was still in British hands. He was guided by Mohawks from Joseph Brant's settlement on the Grand River.

|

Accompanying Simcoe and his Aboriginal guides were several officers including Lt.Thomas Talbot, an officer of the 24th Regiment. Simcoe laid out a fairly detailed plan for the capital probably as a result of this visit. The town was to be located on the south side of the Thames and called Georgina. Simcoe thoroughly examined the site on March 2nd, 1793 and Major E. B. Littlehales, Simcoe's military secretary, recorded "that Simcoe judged the location to be a capital situation, eminently calculated for the metropolis of all Canada. Among many essentials it possesses the following advantages: command of territory - internal situation, central position, facility of water communication up and down the Thames; superior navigation for boats to near its sources and small crafts could probably reach the Moravian settlement. The soil is luxuriously fertile and the land capable of being easily cleared and soon put into a state of agriculture. There is pinery upon an adjacent knoll and other timber on the height, all well calculated for the erection of public buildings. And the climate is not inferior to any part of Canada."

In a letter to Sir Alured Clarke dated May 31, 1793, Simcoe recommended this site.

In His Own Words"For every purpose of civilization, command of the Indians and general defence, I am decidedly of the opinion that on the confluence of the main branches of the Thames the Capital of Upper Canada ought to be situated as soon as possible."

Simcoe's site was not popular with some settlers, one of whom, Richard Cartwright, was a prominent member of the Legislative Council. Cartwright, who never hesitated to disagree with Simcoe much to the governor's fury and frustration, called Simcoe's choice and "perfectly utopian." The woebegone site, said Cartwright, was inaccessible to the settled parts of the province. The word inaccessible was not in Simcoe's vocabulary, for he made exploratory excursions to many distant places during his four years in the province. In addition to this trip to Detroit, he travelled from York to the Thames River, Fort Detroit and the Miamis River in April, 1794. In December of that year he travelled from York to Kingston in an open boat. Then in 1795 he travelled by boat and portage from Newark to Long Point. He also traveled north from York to Lake Simcoe which he named after his father. At the end of each long day on the trail, Simcoe and the others would lie down to rest, but only after all had lustily sung God Save the King as was their custom.

|

|

God Save King George III |

Simcoe preferred English to Native names and he made it a practice to change many, like Niagara to Newark immediately after arriving there in 1792. Chief Joseph Brant resented this, scornfully commenting that "Simcoe has done a great deal for this province. He has changed the names of every place in it." Brant was not the only one to object to the loss of Native names. A traveller named Isaac Weld visited Upper Canada in 1796 and commented, "It is to be lamented that the Indian names, so grand and sonorous, should ever have been changed for others." Most of the citizens thought so too and reversed the process later.

|

|

Joseph Brant |

Whether named Newark or Niagara the collection of decrepit buildings was not much to behold. The newly chosen capital was described by one visitor as "a poor, wretched, straggling village with a few scattered cottages erected here and there as chance or caprice dictated." Another visitor was less kind, calling it "a spot on the globe that appears as if it had been deserted because of a plague."The capital was to see a building boom, however, and while most of the structures were somewhat dilapidated, a few of the newer homes were rather grand buildings, like those of the acting surveyor-general, David William Smith, and the receiver-general, Peter Russell. Newark's growth was not very gradual and when Simcoe left Upper Canada in 1796, there were still only seventy houses in the town.

The town site was centred around some ramshackle buildings beside the water, a complex of small structures which supported saucy little square-rigged sloops that ferried supplies to Niagara from Kingston at the other end of the lake. Located a mile or so up the west bank of the Niagara River near a marshy, breeding place for malarial mosquitoes, the ruinous group of rundown wooden buildings were known collectively as Navy Hall. They had been erected during the American Revolution by order of the Commander-in-Chief of the Forces for use of the officers of the Naval Department serving on Lake Ontario.

|

They had been allowed to fall into disrepair. One of these, which was full of cordage, sails and other naval stores, was to be cleared out and fitted and renovated for the Simcoes' occupancy. Repairs were ordered on "July 26, 1792 and 500 pounds spent on: boards, lime, paint (white, brown, blue and black), 12 locks, 12 bolts, 18 saches, etc," Work was incomplete at the time of the Simcoes' arrival. Sir Alured Clarke informed Henry Dundas that in their best state "they were a paltry residence for the King's Representative." Simcoe wrote to a friend that they were "miserably off for accommodations" and described Navy Hall as "an old hovel that would look like an ale-house in England" even when it was finally completed.

Until the renovation work was being finished, Simcoe had his canvas tents pitched above Navy Hall on rising ground overlooking the river. The tents, which had once belonged to the great explorer James Cook, had been purchased by Simcoe at public auction in London. One was for him and his wife; one was for the children and their nurses; and one was to be used by the servants.

|

On more than one occasion during storms, the family feared the marquees would be blown into the river. Mrs. Simcoe suggested if they ever were, they would all seek shelter under the great dinner table. Long grasses and scattered oak bushes covered the hillside commanding a beautiful view of the river a hundred feet below and of Fort Niagara further down on the opposite side. On clear days one could see across Lake Ontario to the site of the future town of York. Atop the hill the Simcoes had a large bower made of oak bows tied together in which they frequently ate in the summer since it was cooler than the tent.

Hutted half mile below Navy Hall was Simcoe's old regiment, the Queen's Rangers, soon to be relocated to The Landing at Queenston.

|

|

Queenston Village |

The king had authorized the re-formation of the regiment and had personally approved the Queen's Rangers' green uniform with blue cuff and collar bordered with white lace. Breeches were white and the headgear a brimless cap decorated with the crescent badge worn by the original Rangers. The Rangers were housed in 28 log barracks built by them during the winter of 1792-93. An oven had also been constructed so they might bake their own bread.

|

|

>Barracks at Queenston 1793 |

Simcoe's concern for the welfare of the Queen's Rangers, who served under him during the revolutionary war, caused him to fear for the health of his men. He thought the barracks on the banks of the Niagara River were in an unhealthy location caused largely by the thick fog or miasma that frequently rose from the river at this point. As a result the settlement suffered from periodic outbreaks of "fever and ague," a disease now known as malaria. Simcoe was anxious to relocate the men before "they are all buried."

Between Navy Hall and Lake Ontario there were only three habitable houses among the collection of "cabbins, skeletons or ruins," some of which were being repaired for use by government officials. To the south a wide tract of Crown land extended west as far as Four Mile Creek. At intervals along the road to the Falls there were clearings near the bank of the river in which log houses were constructed. Such was Upper Canada's capital in the summer of 1792.

As Simcoe settled in and beheld the size and beauty of the land about him clothed in a primeval forest - giants of magnificent oak, ash, walnut, hickory, elm and maple - he was astounded at its richness. He foretold its great future in the majesty of the lakes, the broad sweep of its rivers and the wonder of the vast woods that blanketed a land as yet untouched by axe or plough. He gazed about him and declared

In His Own Words"It must one day become a great country and govern internal America." [*] Two accurately depicted uniforms of the Butler's Rangers taken standing in front of the regimental colours. Provided courtesy of Zig Misiak, they are from the late Lorne Butler, a direct descendant of John Butler. The uniforms are the only known authentically reproduced colours of uniforms worn by these famous Rangers.

|

|

Original Butler's Rangers Uniforms

e |

Copyright © 2013 Website Administrator