foreword | Historical Narratives | Resources | Links | Contact

SAMUEL LOUNT AND PETER MATTHEWS

History is the endless revisiting, reviewing and rethinking the past.

"Their words were tranquil and serene,

No terror in their looks were seen.

Their steps upon the scaffold strong,

A moment's pause, their lives were gone."

Simple, heart-felt sentiments like this adorned the sides of small wooden boxes made by rebels imprisoned for their part in the Rebellion of 1837. Known as Rebellion Boxes, the tiny containers served as memorials to the men who made them. While decorated in a variety of ways each box shared a common feature: a fond, fervent homage to comrades in arms who had paid the ultimate price. The boxes became poignant relics and reminders of the dread days spent in the dark, dank cells of Kingston's Fort Henry.

Charged with high treason these forlorn Canadians were awaiting transportation to remote Van Diemen's Land, an island known today as Tasmania located off the south-east coast of Australia. Rebels to many but patriots to more, these honest folk faced banishment from all they knew and loved. Yet they still found time to praise with humble works and words two fellow patriots who paid the ultimate price for their part in the ill-starred effort to "burst the chains of tyranny in the province of oppression."

One of these two men was Samuel Lount, blacksmith, businessman, politician and patriot who was born in Catawissa, Pennsylvania on September 24th, 1791. In 1815 he married Elizabeth Soules and the couple had seven children. The Lounts came to Upper Canada in 1818 and settled first in Newmarket where Samuel kept a tavern. He was a skilled woodsman and worked closely with his brother, George during the latter's survey of the townshps of West Gwillimbury, Tecumseh, and Innisfil. From Newmarket the Lounts moved to Whitchurch, then to Holland Landing where they settled in 1822.

Multi-talented Samuel was primarily a blacksmith but he used his considerable skills to good advantage in connection with the construction of the first steamboat on Lake Simcoe, the Sir John Colborne. Kind as well as capable Lount gave generously of his time and talents to all who sought his help. To those who could not afford an axe Lount gave them one trusting that recipient settlers and Natives would one day repay him.

As Samuel's reputation grew so did his stature in the community and this led to numerous offers of public office. He declined them all until 1834 when he decided to run for the Assembly. Lount was handily elected to represent the County of Simcoe. Because of his natural concern for the welfare of others he was attracted to the policies of the Reformers and soon became a close friend of William Lyon Mackenzie.

The second casualty of the cause was Peter Matthews, son of United Empire Loyalists. Born in the Bay of Quinte region, Peter settled as an adult in the Township of Pickering in 1799. He married Hannah Major and they had eight children. Matthews served under Isaac Brock as a sergeant in the Brock Volunteers Militia during the War of 1812 and took part in a number of engagements. He was an honest, prosperous, public-spirited farmer who was well-liked and admired by his neighbours. Because of his desire to help others he became involved in local politics and was subsequently drawn into the rebellion.

In the strange and stormy general election of 1836, the theatrical Sir Francis Bond Head led the Conservatives to a smashing victory. Reformers including Lount, Matthews and William Lyon Mackenzie went down to defeat. Lieutenant Governor Sir Francis Bond Head cast off the cloak of imperial impartiality and stumped the province like a possessed politician campaigning vigorously for king and the Conservatives. His platform was a simple one: "loyalty to the crown and bread and butter on the table." All but a few of the Reformers fell before the onslaught, the lopsided results resulting in the Tories electing 44 and the Reformers 18.

|

|

Fiery Francis Bond Head |

Faced with shady practices at the polls that included intimidation for any daring to vote Reformer and an entrenched ruling clique known as the Family Compact, Mackenzie, Matthews, Lount and others began to question whether democratic change was possible within the existing political system and drifted irrevocably and aimlessly towards rebellion. When legitimate methods failed to win a voice for reformers in the province's affairs, the disillusioned Lount and Matthews joined Mackenzie and other discouraged Reformers in a daring plan that would bring about drastic change by throwing the rascals out - literally. They prepared for war.

|

|

Converting Ploughshares into Pikes |

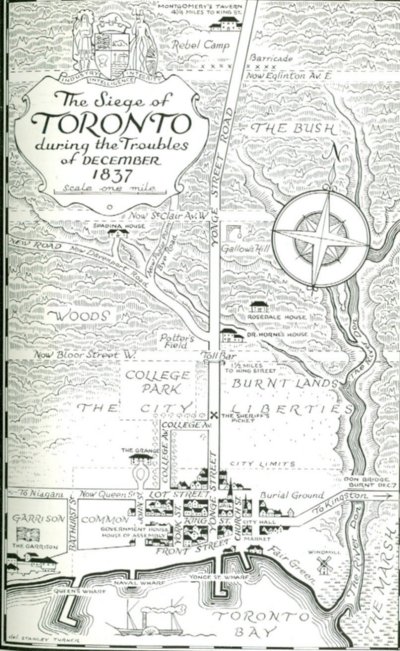

Matthews became one of Mackenzie's military leaders. With a band of sixty men he was assigned the task of creating a distraction at the bridge over the Don River in order to divert government forces from attacking Montgomery's Tavern[* See Below] until rebel reinforcements arrived. The rebels successfully torched the bridge before being driven off by militiamen. Matthews and his men retreated towards their homes in Pickering.

|

|

Montgomery's Tavern Is Torched by Head |

Around six o'clock on Saturday December 9th, they arrived at the farm of John Duncan in East York where they were fed and housed for the night. A Tory living nearby noted numerous footprints in the snow around his neighbour, Duncan's house, became suspicious and rode for the militia. They responded quickly and broke into Duncan's house around midnight. When Matthews, a big, powerful man, was poked awake with a rifle he grabbed the weapon and flung it and its owner across the room. Superior numbers soon overpowered the patriots, however, and they were marched off to Toronto and to jail.

|

|

Toronto During the Rebellion 1837 |

Meanwhile, Lount, who had no military background, was assigned the rank of Colonel. Because of his popularity in the area south of Lake Simcoe, Lount had little difficulty attracting neighbours to the rebel cause. When called to arms on December 4th, 1837, Lount and some ninety men struck out for Toronto. After a hard march of 30 miles they arrived hungry and exhausted at Montgomery's Tavern where they joined other rebels armed with pikes, poles and a few rifles. They could only take the captial by surprise and that chance was rapidly slipping away from them.

For two days while as series of tragic accidents, comic terrors and fatal debates over grand strategy paralyzed the rebel movements, the provincial militia was pouring into the capital. Late on Monday, December 4th Alderman John Powell burst breathlessly into the bedchamber of Lieutenant Governor Francis Bond Head. Waking Sir Francis, Powell informed him of the outbreak of rebellion in Upper Canada. The citizens of Toronto frantically prepared for the anticipated rebel onslaught. In actual fact the few hundred untrained, inexperienced and dispirited farmers assembling as Mongomery's Tavern could only have taken the capital by surprise, a slight chance that was rapidly slipping away from them.

On December 7 the loyalist army that included a well-armed Head under Colonel Fitzgibbon marched up Yonge Street to scatter the enemy. Meanwhile the Mackenzie's ill-armed, motley crew trudged down Yonge Street to attack the capital. Those with rifles marched in the forefront and behind them came the pikemen. Bringing up the rear were the rest of the rag-tag rustics bearing poles, sticks and staves. All were bundled against the bitter cold in ill-fitting homespun.

Within half a mile of the city,(not far from where Maple Leaf Gardens is today) shots were fired at the rebels by an advance guard of Loyalist militiamen, who then took off for Toronto. Rebel riflemen in the front rank returned the fire, then they dropped to their knees to reload. Those in the rear heard the roar of rifles and then to their horror saw the front rank disappear. Fearing they had all been felled by a fusillade, they panicked and ran. Similar kinds of chaos characterized the remainder of the rebellion and within days, Mackenzie and his men had scattered to the four winds with Head and his hunters in hot pursuit. It was all over in less than half an hour.

The following notice appeared in the local press. 500 Pounds For S. Lount

A tall man, say six feet or rather more, long face, Sallow complexion - black hair with some grey in it - very heavy, dark eyebrows, speaks rather softly.

Lount first travelled west then set off across Lake Erie. After two difficult days he sighted the United States shore but before he could land a strong gale arose which promptly returned him to the mouth of the Grand River. Here he was mistaken as a salt smuggler and arrested. Later Lount was recognized as a rebel by a local magistrate and marched off to Toronto. When the wind blew off his hat an old red nightcap was placed on his head. This humiliation was quite in keeping with the bitterness which prevailed at the time. Meanwhile, Matthews awaited his fate in the Toronto jail.

|

|

The Rebel Rounded Up |

|

|

Captured Rebels Taken to Jail |

On January 18th Lount and Matthews were charged with high treason, placed in irons and thrown into the darkest, dirtiest cell in the Toronto Gaol. Lount occupied a dismal cell 5 feet 6 inches wide and 4 feet 4 inches deep. They and other rebels remained there for the next three months during which tme they bore the appalling conditions bravely. Until he was led out that fateful April morning to be hanged, Lount kept up the spirits of others by praising their cause and promising that "Canada would yet be free."

|

|

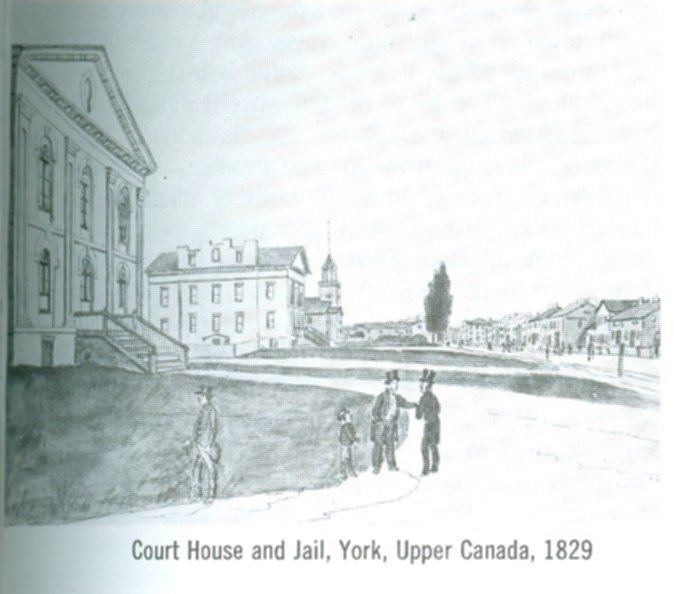

Toronto Jail |

The Toronto Jail, a historic landmark of despair and misery with palisaded yard from which death seemed a merciful excape is shown as it was in 1838. "It might well be written that its cells have been awash with tears and each brick of the structure is a memorial to blasted hopes."

Their lawyer, an ex-Patriot named Robert Baldwin, charged a fat fee but did little to earn it. He convinced the two men to plead guilty and ask the judge for mercy. The guilty plea eliminated the necessity of a trial whereas a jury trial might very well have meant acquittal. Their fate was sealed. It was the view of Chief Justice Sir John Beverley Robinson, who presided at the trials of those charged with insurrection or treason, that "some examples should be made in the way of captial punishment." Robinson's view prevailed in the case of Lount and Matthews. Lount was offered his life in exchange for information on other rebels but he refused to inform on his fellows. He and Matthews were convicted and sentenced to be hanged.

Elizabeth Lount sought valiantly to convince Sir George Arthur to spare the men's lives. With a roll under her arm she mounted the steps of Government House dressed in her Sunday best. The petition she bore was signed by thousands. Even loyal residents were moved with pity for Lount whose many good, generous actions were well known throughout the colony. She was ushered into the presence of Sir George Arthur, a soldierly, formal-looking man with neat whiskers. Arthur gazed at her coolly as with shaking hands she presented her petition calling for clemency. Despite the fact that very act of signing the petition was considered seditious and a dangerous thing to do, it bore the names of 8000 citizens sympathetic citizens.

Arthur, the former keeper of convicts at Van Dieman's Land, was unmoved. Prior to his Canadian appointment Arthur had served as head of a penal colony where he presided amidst anguish, misery and despair, his justice administered with the chain, the lash and the rope. Compassion was foreign to his nature and he easily held his emotions in check. Lount must pay the awful price unless, of course, he chose to "rat on the other rebels." At his negative response Elizabeth went to pieces and fell to her knees imploring him not to hang her husband and leave her seven children fatherless. It was to no avail. The very popularity of Lount and Matthews had sealed their fate. The government was determined to use these two well-liked men as extreme examples of the price of insurrection.

|

|

Elizabeth Lount Begs for Her Husband's Life |

"The future historian will drop a tear over the fate of Lount and Matthews while his blood freezes within him to think that a human being once existed, who callous to feeling, could confirm a hard sentence, and be unmoved by the cries for mercy from thirty-thousand of his fellow-subjects, consign to an ignominious death, men who were unquestionably honest and brave."

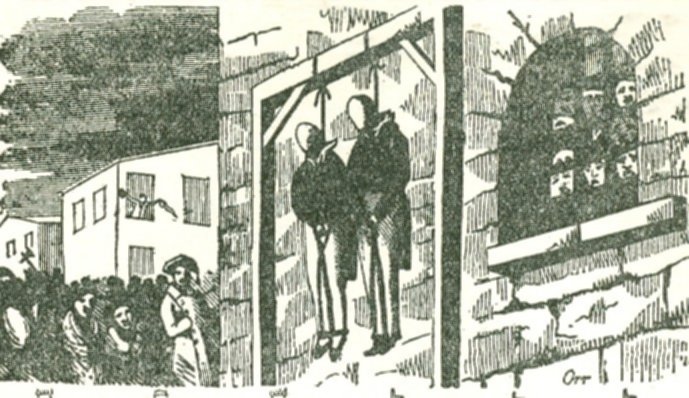

Meanwhile the sound of pounding hammers broke the silence of the frosty air while prisoners looked on the gallows going up. To ensure the widest possible prison audience for their execution, the scaffolding was relocated prominently in the prison yard so that all prisoners could see the execution. "At length the morning dawned, the hammering ceased and there the gallows stood a finished work." William Jarvis, sheriff of York, presided at the hangings of Lount and Matthews.

The story of Lount and Matthews must be told in the words of a man who shared their cell in the grim institution that occupied the north-east corner of King and Toronto Streets.

"The hours of April 12, 1838 were the saddest we ever spent. None of us could sleep and we were all early astir. It was a fine, cool spring morning. Looking through the window of our room we saw the scaffold. It was built by the late Mr. Storm. His foreman was Matthew Sheard then a fine young Yorkshireman and afterwards mayor of the city. He was expected to share in the work of building the scaffold. 'I'll not put a hand to it,' he said. 'Lount and Matthews have done nothing that I might not have done myselt and I'll never help to build the gallows to hang them.' So without the foreman's assistance, the gallows was created near the spot where the police court building now stands. Around the gallows the Orange militia stood in large numbers with their muskets. The authorities dreaded a rescue. While we were watching and talking we heard steps on the stairs and then the clank of chains. It was poor Lount coming up guarded by his jailers to say goodbye to us. He stopped at the door. We could not see him but there were sad hearts in that room as we heard Samuel Lount's voice without a quiver in it give us his last greeting.

'Be of good courage boys I am not ashamed of anything I have done, I trust in God and I am going to die like a man.'"

As they passed fellow prisoners on their way to the scaffold Lount is reported to have said, "We die in a good cause; Canada will yet be free."

Lount and Matthews moved slowly to the ladder and mounted its eight steps to the gallows without stumbling. They left life as they had lived it, with complete calmness and self-control. When they reached the top of the scaffold, Lount turned slowly and bowed to the hundreds of heads that watched from the windows of the prison. He and Matthews then knelt in prayer. For the last time they looked up at the sky, then at the faces of those around them. White hoods were placed over their heads and the noose tightened around their necks. The freezing air was unbroken by any sound. All eyes were fixed on the two big men. The trap door opened, the ropes hummed taut and side by side they plunged to their deaths in the early morning hours of Thursday, April 12th, 1838.

|

|

Execution of Lount and Matthews, April 12, 1838 |

Two of the worthiest men in the rebel ranks were gone, men who would have made a significant contribution to life in the little colony. The crowd dispersed having seen justice or injustice done. Over the next weeks and months the phrase "judicial murder" was frequently heard.

Fearing a demonstration of sympathy and support for the two men whom many considered martyrs, the government refused to turn the bodies over to their families. Instead they had them buried in Potter's Field a graveyard for paupers on Bloor Street. The inscription bore only the names: Samuel Lount and Peter Matthews.

Twenty-one years later on Monday, November 28th, 1859, William Lyon Mackenzie along with Lount's sons moved the bodies to the Toronto Necropolis Cemetery. In 1893 "Friends and Sympathizers" of the two men erected a monument to them, a fifteen-foot, grey, granite structure surmounted by a broken column to indicate that their lives were cut off before their work was done. The monument was completed on Wednesday, June 28th, 1893. People have long memories. Canada had done justice to their memory.

The inscription reads as follows.

Peter Matthews was the son of Captain Thomas Elms Matthews, a U.E. Loyalist [?], who fought on the British side in the American Revolutionary War and at its close settled his wife and family in the Township of Pickering in the (then) County of York. Peter Matthews, the son, belonged to Brock Volunteers during the War of 1812 to 1815 and fought in various battles of that war. He was known and respected as an honest and prosperous farmer always ready to do his duty to his adopted country and died as he lived -- a patriot. PETER MATTHEWS / Late of Pickering / County Ontario / Born 1786 / Died 12th April 1838

Erected by their friends & sympathizers / A.D. 1893.

The Rebellion of 1837 was of little consequence as far as military encounters were concerned, but the very fact that it occurred marked the a turning point in Canada's constitutional development.

|

|

Plaque to Lount and Matthews |

|

|

Samuel Lount's and Peter Matthews' graves are marked with a broken marble column to symbolize two lives cut short.

"Their words were tranquil and serene, |

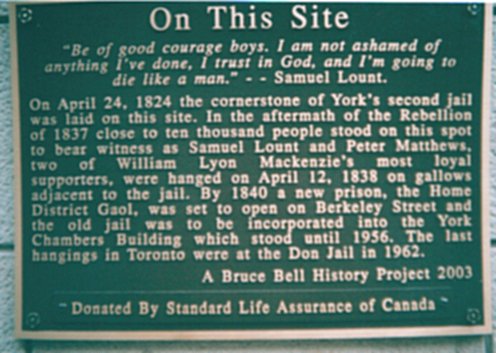

[*] That site today is a post office on Yonge Street just north of Eglinton Avenue. Montgomery was also sentenced to be hanged and he swore at his sentencing that he would outlive the jury and the judge. His sentence was commuted to transportation but he escaped and fled to the States. When amnesty was granted in 1843 he returned to Upper Canada and lived until the age of 96 by which time most others prominent in the rebellion had died. The bronze plaque on its side was a 2003 Bruce Bell History Project. It is copied above and gives the details of that tragic event.

ON THIS SPOT

[Number 1 Toronto Street]

[**]In the aftermath of the Rebellion of 1837, close to 10,000 people stood on this spot indicated below which is now occupied by 1 Toronto Street at the corner with Court Street. They bore witness as Samuel Lount and Peter Matthews, two of William Lyon Mackenzie's most loyal supporters, were hanged on April 12, 1838 on gallows adjacent to the jail. By 1840 a new prison, the Home District Gaol, was to open on Berkeley/Front Street. The old jail which became the city's first insane asylum was incorporated into the York Chambers Building which stood until 1956. The last hangings in Toronto were in the Don Jail in 1962.

|

|

1 Toronto Street. |

Copyright © 2013 Website Administrator