foreword | Historical Narratives | Resources | Links | Contact

VAN DIEMAN'S LAND

History changes with the impact of new beliefs, thoughts and reflections.

If Upper Canada's rebellion exhibited aspects of farcical comedy, its consequences for convicted rebels were acute tragedy. Some were hanged for high treason. Others fated for the gallows had their sentences commuted as an act of mercy to transportation to a penal colony. Some whose sentences were so moderated lived to suffer and sorely regret this clemency. In all seventy-two individuals were condemned to be transported as convicts to Van Diemen's Land, a devil's island located at the other end of the earth.

"The most humane punishment the wit of man ever devised." That is how life for criminals in Van Diemen's Land was described by Sir George Arthur. His praise for the penal colony was a bit biased since he served as its chief enforcer from 1824 to 1836. As lieutenant governor of the convict colony Arthur's word was law. While the penal complex was within his "iron grip," he established a reputation as a man whose manner was "most tyrannical, arbitrary and capricious."

Sir George Arthur tyranny took another form when he decided that the island's Aborigines should be rounded up and confined to a remote location. To accomplish this he developed what was described as the infamous Black Line. The white population of male free settlers and convicts equipped with 1000 muskets, 30,000 rounds of ammunition and 300 pairs of handcuffs formed a human chain in an attempt to drive the remaining Aboriginal population down a narrow isthmus to the Tasman Peninsula. "Every white man in Van Dieman's Land," he wrote to London, joined the line "with the most zealous and cheeful alacrity." Because the Aborigines knew the bush so well they easily eluded their pursuers. The drive demoralized the tribes, however, and they fled from the territories as word spread among the frightened people. "Plenty of horseman, plenty of soldiers, plenty of big fires on the hills," lamented one native woman. Within four years all of the original inhabitants with the exception of one family had fled.

|

|

Sir George Arthur |

While it was, perhaps, preferable to hanging, few banished Canadians shared the conviction of Arbitrary Arthur about the benefits of exile to that far-off place. Existence on a chain gang was bleak and grimly brutal, made moreso by the despotism of the lieutenant-governor who was known as the Tyrant of Tasmania because of his rigid rule. During his tenure down under Arthur developed a reputation for viciousness. It is reported that in his thirteen years in the penal colony he signed some 1500 death warrants. The condemned men were all hanged on a gallows supposedly in sight of Sir George's dwelling.

Sir George Arthur considered the island one large prison, a personal fiefdom in which his word was law. He resented and resisted any threat to his absolute power and vigorously opposed the introduction on the island of representative government and trial by jury. He muzzled the press and autocratically dismissed anyone who opposed him. This angered and alienated the emancipated prisoners and free settlers who also lived there and they flooded Downing Street with complaints. Finally the Colonial Office acted and Arthur was ordered to return to England "with as little delay as possible." His recall resulted in widespread rejoicing among convict and colonist alike.

|

|

Notice: Arthur Orderd Home |

One local newspaper headlined his leaving, celebrating the "blessing" of his departure by calling it "deliverance from an iron hand and acts of abomination." "Rejoice," proclaimed the headline "for the day of retribution has arrived."

On his return to England Sir Arthur rehabilitated his reputation for he was among the first to be knighted by the young Queen Victoria in 1837. His reward for a job well done was a new sinecure as lieutenant-governor of Upper Canada. He was told to "clean up" after the Rebellion. This man labelled "tyrannical, arbitrary, and capricious" was directed by the Colonial Office to deal humanely with the rebellion aftermath in a way that tempered law with leniency. Sir Arthur was the last man to provide leniency. He knew better and refused to follow such foolish orders. He would punish the patriots.[See Below *] Arthur was subsequently criticized for his severity in general towards those involved or suspected of being involved in the rebellion. In particular, he was censured for the execution of two prominent and well-liked Upper Canadians, Samuel Lount and Peter Matthews.

In Upper Canada following the trials and sentences of transportation, political prisoners were fettered and manacled in readiness for their removal to the Yonge Street wharf for shipment to Kingston where they were imprisoned for a time at Fort Henry. From there they were taken to England and confined in London's notorious Newgate prison, the depository of guilt and misery whose very stones were considered 'death-like' and place of infamy where lice were a constant companion. It "wore a brooding and haunted air" and was the threshold from which prisoners left for the gallows. Following cruel confinement in this sordid, savage place, they were transferred with British convicts to Liverpool from whence in ex-slavers and other old hulks bearing such names as York, Marquis of Hastings, Buffalo and Canton, they set sail for Van Diemen's Land.

|

|

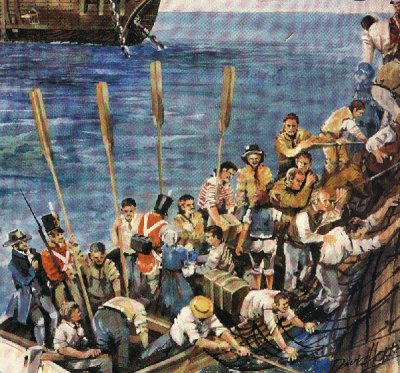

Boat Load of Prisoners taken to ship |

|

|

More Prisoners being loaded onto shp |

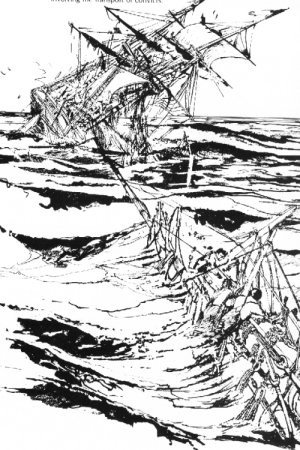

The endless journey took on average 120-plus days in uncharted waters and heavy seas during which some ships simply disappeared beneath the waves. Eighty-nine wrecks involving convict vessels occurred around the island with great loss of life. Illness also took a heavy toll, in one instance 145 prisoners out of 499 dying en route.

|

|

Sketch of two ships sinking |

|

|

Rowboat full of rescued prisoners |

During the first half of the 19th century 100,000 convicts from all over the British Empire were transported to the prison island. On average during those years the island was shared by 37 thousand convicts and 30 thousand settlers and inhabitants, the latter "free and without stain."

On arrival at Van Diemen's Land the survivors of the voyage were assembled and warned by Sir Arthur that they must without question follow the letter of the law or suffer punishment of exemplary severity. They were then marched off to Hobart Penitentiary, a walled compound that encompassed crowded dormitories and tiny, terrible isolation cells. The convicts wore jackets and trousers in yellow and black to permit easy identification at a distance. They wore as well a skull-cap of stiff, sole leather and a "pair of thick, clumsy shoes without socks." These clothes did not last long and prisoners were soon bare-footed and exposed to biting winds and storms. Shovel, pick-axe, wheel-barrow and cart were implements of toil. Blistered and bleeding hands and strained muscles were the daily diet of each man. They worked eight hours a day in winter and twelve in summer. They ate a breakfast of gruel, a lunch of salted meat, vegetables and bread and a supper identical to their breakfast.

The work ethic that entailed exploitation, brutal labour and the lash was intended to curb conduct and reclaim 'lost' lives. "I think," said Sir Arthur, "it not possible that a better employment could be found for some of the more refractory convicts than employing them in working coal mines." This terrible task was dreaded by all convicts. Conditions 30 metres below sea level were harsh, the men having to

|

|

Sketch of prisoner working in coal tunnel |

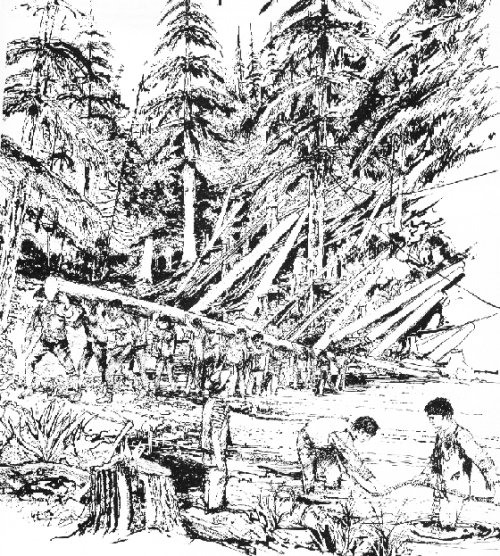

hew coal with picks in narrow frequently flooded tunnels that were filthy, cramped and claustrophobic. Most prisoners' time was spent cutting timber or quarrying, breaking and transporting rock for roads in Hobartown.

|

|

Prisoners cutting down trees |

A carefully graded system of rewards and punishments was used to curb conduct and reclaim the "lost lives" of the convicts. At one extreme were penal settlements where conditions were harsh and labour was unrelenting. At the other extreme was the "assignment," a system of servitude for years for one or more of the settlers.

Solitary confinement was feared most. The confinement cells were little more than stone crypts twenty-seven inches high where men could be confined in darkness for up to four months, twenty-four hours a day. Many went insane. Particularly difficult inmates served their sentences in chains, leg irons weighing between ten and thirty pounds that once clamped on would not come off even for a day until the sentence had been served. Many of the inmates died from disease and exhaustion.

Each morning prisoners were assembled to watch the bloody beating of 10 to 20 men tied to the "inhuman" triangle. The cat o' nine tails with nine doubled twisted and knotted cords was used. Ten to 200 lashes were laid on, in the latter case repeated at intervals over a day or so. Those chosen to apply the lash were stout, robust men. Flogging often turned a man's back into a mangled piece of flesh from which enough blood ran to fill his shoes "till they gushed over."

|

|

Prisoner being lashed |

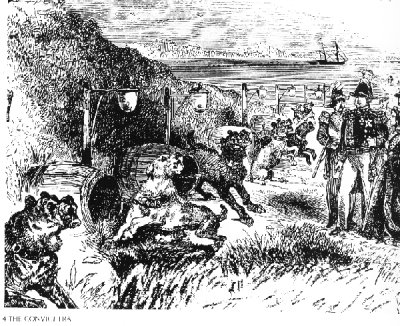

Escape attempts were common but few were successful. Both dogs and armed sentries controlled the movement of all persons. Across exit points eighteen savage dogs [mainly deer hounds and mastiffs] were chained so close to each other "that man could not pass between them without being seized and torn to pieces."

|

|

Snarling dogs keeping watch |

The punishment for attempting to escape was the treadmill, an immense wheel 30 feet in diameter kept in constant motion by thirty prisoners. Every four minutes a man descended at one end while another mounted the wheel at the other. The cycle lasting two hours was then repeated.

After several years prisoners were eligible for parole which meant they were no longer shackled inside the prison camp although still forbidden to leave their section of the island. There was little work and lots of time on their hands and before long many parolees disappeared into the bush where they became either the pursed or the pursuers or bush-rangers. "A rogue was used to catch a rogue." Paroled prisoners were employed to bring back the outlaws dead or alive for which the pursuer's pay was a pardon.

Pardons normally were granted several years after a successful period on parole but they did not include return transportation. Each exile had to find his own way home, an exhausting trip using many methods of travel over an extended period of time. One Upper Canadian finally made it home after 22 years arriving back in Brockville in 1860. Seventy-two Upper Canadians were transported to Van Diemen's Land and of this number 13 died on the island prison. There is no record of another 40 ever having returned. The remainder made it back to the United States of America where most remained in exile from their native land along with many others who had fled to the States earlier.

"What Canada lost was a small army of so-called renegades, among whom were some thugs, criminals and a sprinkling of harebrained individuals but the great majority were men of character, ability and ideals of good citizenship. Canada was vastly the poorer for their exile."

The 17th century Dutch navigator, Abel Tasman, discovered the island in 1642 and named it Van Diemen's Land after his patron, Anthony Van Diemen, the governor-general of the Dutch East Indies. Its use as a penal colony lessened as the colonial population grew and transportation decreased and finally ceased in 1853. The hated name, "Van Dieman's Land" which carried the stigma of penal colony shed its savage image and was altered on the 1st January, 1854 to Tasmania.

[*] "A successful revolution alters the status of the rebel who immediately becomes a patriot and a halo is thrown about the actors in the drama. Failure leads to severe punishment and persecution of the participants."Copyright © 2013 Website Administrator